Alpha ex-Ante

How evolving capital markets are shaping a new theory of the firm

These days, it is hard to imagine a market headline that you would consider surprising. Whether it’s the circular financing arrangement of AI companies or the baldness with which stocks of uneconomic enterprises are promoted, incredulity is in short supply. Nonetheless, Apollo found a way to surprise me this week.

Joe Lonsdale’s 8VC announced a strategic partnership with Apollo Global Management that marries venture equity investment with private credit. The exact nature of the partnership is not entirely clear, but Lonsdale is plain spoken about its motivation,

“While venture capital is well suited to funding technological breakthroughs, it’s not sufficient to fund the huge projects that are required to increase our national productivity with the next wave of transformative technologies like AI, robotics, autonomous systems, biotechnology and nuclear energy…”

There had been some reticence to admit that you cannot achieve the returns venture investing requires when so much capital is needed for physical assets. For all the VC bluster about the need for a defense, energy and manufacturing renaissance, the business model does not fundamentally support asset heavy balance sheets. Marrying venture investing with structured debt solves a variety of issues for VCs, lenders, founders and investors.

Old Paradigms

It also represents a continued evolution of markets. Venture, and to some degree, private lending, were once seen as a form of bridge capital to public markets. As the attractiveness of public markets has waned and the scale of private credit has grown, permanent private ownership has become an aspirational structure.

In a prior era, software companies viewed a public offering as the top of the mountain, while asset-heavy companies needed to be traded between private hands until there was scant value in the equity and listing was the only option left. The most innovative companies today have valuable intellectual property like the software of yore, but their products require real capital formation in the form of factories, foundries, data centers and infrastructure.

Venture capital historically used little debt, if any, because the business models already had a high degree of operating leverage. Private equity gravitated to real economy businesses because their assets were easier to leverage to enhance the otherwise uninspiring returns on equity. As these two worlds merged, the obsolescence of the old model presented a variety of problems.

I recall showing Julius Krein, editor of American Affairs, an Anduil hype video for one of their drone releases. “All I care about is how many they can produce,” he responded. It carried more significance than I realized at the time. These companies’ innovations are only valuable to the degree that they can also control and scale the production of physical goods.

Early stage venture investors face a constant barrage of dilution in choosing to back an early-stage industrial company, while there isn’t yet the cash flow nor the asset base for debt markets to provide credit solutions. This has led to more essays than investment in what was becoming a glaring capital mismatch.

The 8VC-Apollo partnership theoretically presents a solution. Again, without the details of the partnership we can only speculate what it will look like in practice. One possible expression could be in the form of a “full-stack” term sheet for companies with promising technology that requires real capital formation. A defense tech company could arrange, in a single round, equity capital into an R&D entity, with a contingent term-sheet for debt capital to fund some form of off-balance-sheet SPV that would own the assets required to actuate the business model.

The venture investors are able to invest less capital with a higher degree of visibility on future dilution. The private credit lenders get to structure the credit de novo, without having to deal with broken capital structures or appeasing pre-existing senior lenders. The entrepreneur can raise at a higher “asset-lite” valuation. The LPs of VC and debt funds, via the terms of both, replicate the governance control of being majority equity owners.

Engineering Liquidity

“Alpha” is a fickle term. In public markets it is relatively straightforward. Your benchmark represents the cheapest available option to capture the returns of your chosen market. In private markets, an umbrella term that often serves as a placeholder for a variety of strategies, alpha is in the eye of the beholder (the LP). In practice, it means absolute returns, an overly academic way of saying “not negative.” With rare exception, public markets will offer more opportunities for higher returns. Private markets may outperform or underperform publics over a specific time period but their core value proposition is that they won’t be negative.

Much has been said about the benefits of lower volatility, however illusory, and that the incentive structure of allocators has contributed to the growth of private assets. This critique is constantly overstated. It is almost always levied by public markets managers whose own relationship with allocators is dictated by a raj of arcane risk-reward statistics. Their argument is one of measurement, not results.

On a total return basis, active public managers have consistently been bested by private assets and their very own benchmarks. The harsh reality is that as private markets have grown, capturing financial asset beta has required their inclusion on portfolios, while the pursuit of alpha has been de-emphasized. This disadvantages public managers whether or not they can or have generated alpha in the past.

Combining venture investing with private credit represents an evolution of capital markets where alpha can be engineered ex-ante. That is, liquidity and returns are contractual agreements, not market outcomes. This is a bold claim that I will try to unpack as most of us live in a world where transactions between willing buyers and sellers is the ultimate arbiter of value.

In “The Covenant Structure of Yield in Private Credit,” Elham Saeidinezhad asserts (emphasis mine),

“Unlike public markets, where valuation is anchored in continuous pricing, dealer intermediation, and standardized benchmarks, private credit operates within a legal environment where liquidity is neither spontaneous nor infrastructurally produced. In this setting, capital movement depends entirely on what is permitted by contract. Yield, similarly, is not discovered through trading activity but structured ex ante through covenants that govern exit pathways, embedded optionality, and cash flow dynamics.”

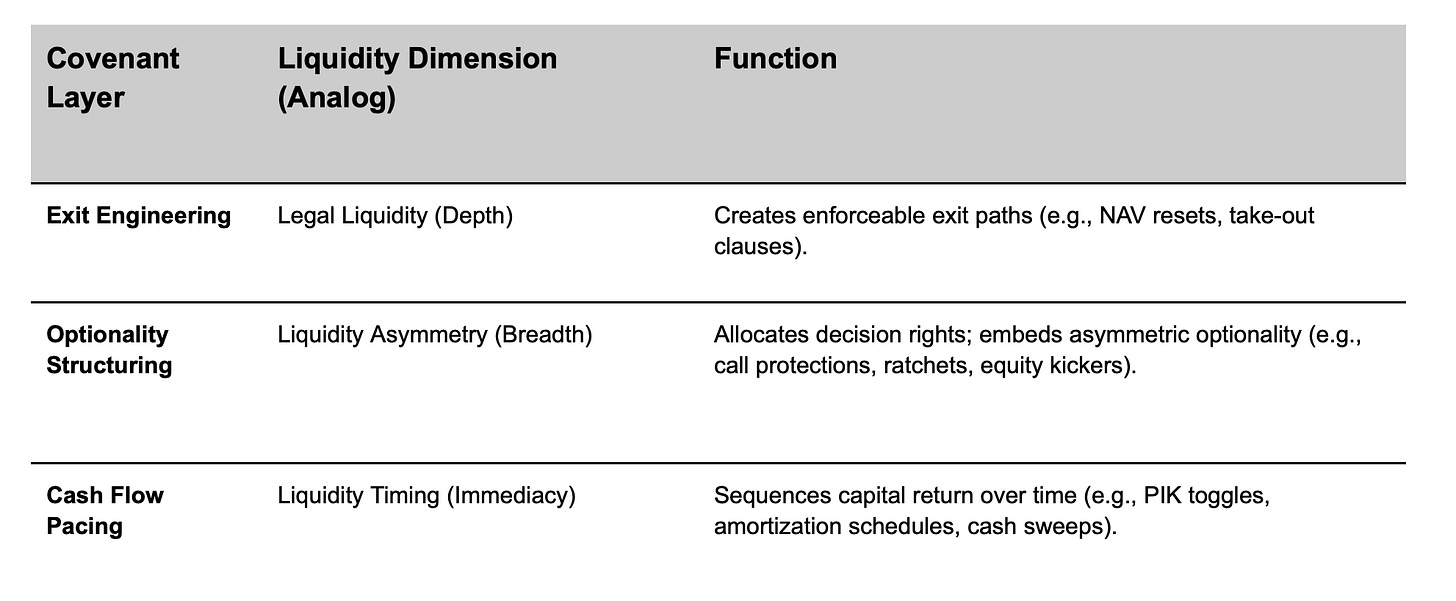

Saeidinezhad goes on to lay out an approach to private credit valuation dubbed a “covenant-centric” model that effectively links the sources of private credit liquidity to their public markets equivalents: depth, breadth and immediacy. As corporate life unfolds, private credit creates liquidity via the covenant structure.

I will leave it to the reader to assess the veracity of this model, but in observing that private credit returns routinely outpace equity returns for similar company profiles, the approach seems prima facie correct. However, that also means we must call into question the more philosophical idea of ‘what is debt’?

Disappearing Boundaries

There is no hard line that turns a financial instrument from equity to credit, any attempt to distill it falls prey to abstraction. Who has corporate control and what claim they have on cash are the core concerns of the investor, the LP has to determine which “bucket” it belongs in. In trying to understand how capital markets are evolving today, it matters not.

I elicit this paper in part to highlight how similar venture capital and private credit are. While they may be perceived to be sitting on opposite ends of a spectrum they both seek to define outcomes contractually at origination. Venture uses liquidity preferences, ratchets, and vesting schedules to structure liquidity in a variety of outcomes. Where private credit uses contractual terms to manage downside exposure, venture capital uses those terms to capture more economics in upside scenarios.

If you want to see what this might look like in a live environment, look no further than Meta and Blue Owl’s massive bond issuance for its Hyperion data center in Louisiana. The $27.3 billion bond issuance is the largest investment grade bond sale ever. That investment grade rating comes with some footnotes though.

As FT Alphaville reports, the issuer is neither Meta nor Blue Owl, but rather a bankruptcy remote JV called Beignet Investor LLC. The issuer’s investment grade rating is courtesy of a 20 year lease agreement from Meta, who is on the hook to pay even if construction is delayed and will come out of pocket to finish the project up to 105% of the budget. FT’s Wigglesworth writes,

“Meta and Blue Owl’s Beignet structure blurs the line between traditional corporate bonds, project finance and private credit, and shows how the circa $174tn global fixed income market can actually be pretty adaptable — if you’re willing to do a bit of finessing”

Citing a JP Morgan research note,

“From a fundamental credit perspective, we are not aware of a prior A+ rated corporate bond with this degree of structural complexity and single-asset dependence. The Beignet notes are issued by a bankruptcy-remote vehicle, fully secured by the Meta-leased data center, and rely on project-finance-style cash waterfalls, reserve accounts, and mandatory amortization. Credit strength ultimately depends on Meta’s lease and residual value guarantees, not on diversified corporate cash flows.”

Worth noting, these bonds are already trading at a premium. Also notably, these bonds are 144-A for life, meaning they will only ever be able to be traded among institutional purchasers. Despite the size of the issuance, they are currently excluded from bond indices.

While neither venture capital nor private credit, the structure highlights the appeal of hybrid structures. Meta gets investment for real capital formation without having to take the debt on their balance sheet, even though their own lease is the sole security. The lender sees their credit improve as the project reaches completion, but they are virtually guaranteed a return at origination. Wigglesworth,

“[I]t’s very clearly a bit of clever financial engineering designed for Meta and its partners to have their cake and eat it. The cute structuring means that Beignet benefits from Meta’s creditworthiness, but Meta’s creditworthiness is magically not impacted by the financial liability that its long-term lease guarantee constitutes — at least according to S&P.”

The entire logic rests on the idea that the project cash flows are of little value to the equity if they require balance sheet capacity. It is fine if creditors get a greater share of cash flow from the project earlier because the equity is valued based on the companies’ ability to utilize the assets, not the assets themselves. 8VC and Apollo want to create this structure at the earliest stage of companies’ lives.

The idea of keeping corporate entities asset-lite is nothing new. In fact, fissuring the economy into each component of value creation has been the standard operating model. That is, “the separation of both labor and physical capital from profits, across the legal boundaries of different companies, rather than having the footprint of all three largely reside within the same company.” Apple is perhaps the most successful expression of this model, while Boeing demonstrates the pitfalls of following this model to its logical conclusion.

This model worked well for equity owners while it hobbled economic growth. Moving assets off the balance sheet but retaining profits drove up multiples and distributable cash, but it took away the incentive for the most profitable companies to also be the largest investors. Until now.

The AI arms race has put capex back on the menu. Showing the market you are building out digital infrastructure is now both a strategic requirement and driver of valuation. For the largest tech companies this bet amounts to a few years of cash flow, ultimately insignificant in the arc of time, especially if they are right about the future. However, for new firms, the capital markets have not fully figured out how to finance their growth.

The expansion of private credit beyond the confines of the sponsor-backed LBO market into growth companies and asset-based lending has spawned a new vision of the firm. The modern firm is not a self-contained entity of assets and labor, but a choreography of contracts that govern capital, risk, and production. Its value resides less in ownership and more in the legal architecture that determines how cash moves.

New Paradigms

Private capital now operates closer to the source of return creation, negotiating liquidity and yield at the moment of origination rather than hoping to harvest them later from market transactions. What we call “markets” increasingly look like the post-production department of finance. They are places where the finished product of private contracting gets sliced, repackaged, and re-rated for public consumption. And so the modern firm has become less something you invest in than something you invest through.

The terms we use to describe financial assets; public, private, debt, equity, have always just been a form of shorthand for the cascade of agreements each represents. Assets, liabilities, employees, and cash flows now orbit within a web of paper: term sheets, leasebacks, SPVs, revenue shares, covenants. The firm has become a collection of claims, its boundaries drawn less by what it owns than by what it can obligate.

The dividing line between debt and equity has melted into a gradient of structured promises. Credit investors now participate in upside through covenant engineering; equity investors protect their downside through liquidation stacks and preferred waterfalls. Both are just negotiating their place in the same contractual choreography. The growth of this phenomenon should encourage investors to evaluate their portfolios accordingly.

Really enjoyed this ☝️. It seems the structure you reference between Meta and the paper entity Beignet sets up a situation where if the AI boom swings away from CapEx suddenly, then Meta walks away from the lease guaranty, the lender could be stuck with significant losses.

A good example of the financial engineering that led to the mortgage backed security, 2008 GFC where collateral for loans were worthless.

I saw this in the industrial space recently (2021-22) when Amazon walked away from a number of distribution center deals it had under contract. A bunch of developers took steep losses. Luckily my partners and I weren’t one of them.

Appreciate the thoughtful insights as always!