Credere

Jay Newman, Walter Wriston & David Graeber on Sovereign Debt, China and what it means "To Believe"

"Countries don't go bankrupt, which is completely accurate and totally useless if you're a creditor"

- Jay Newman from Elliott Management quoting Walter Wriston

As the US Dollar continues its seemingly inexorable rise, sovereign defaults will almost surely follow in its wake. A more global, interconnected financial market has meant periodic waves of sovereign credit crises since the 1970s. The terms have evolved; “Emerging Markets” have been stealthily recast as the “Global South” since nothing can be emergent forever. However, Poorer nations' issues have remained unchanged: Resource-rich, held back by unrest and corruption, fruitlessly trying to compete with developed countries with a multi-generational head start.

For a long time, the belief was that these nations were just a little behind, that importing some liberal reforms and the best of what has worked, they could all look like Southern California in a few decades. This belief belied a fundamental truth about how the global economy had changed, in his essential The Brazilianization of the World, Alex Hochuli observes:

The technologies and associated industries of the Second Industrial Revolution were no longer in the vanguard. An economy based around the technologies of petroleum, rubber, and steel—say, the manufacture of automobiles—was no longer the stuff of “high value-add.” The important stuff—the really valuable ideas—were now protected by intellectual property rights, inaccessible to a country such as Brazil. Global South and North are therefore no longer avatars of past and present, with the former slowly catching up to the latter, but now seem to exist in the same temporality.

There are the markers of development, broader access to social media, e-commerce, but “whatever bluster there may be about the ‘new middle class’—or, really, a working class that has entered consumer society precariously, now able to buy a fridge and a TV, and maybe even go to university for the first time in family history, but which has not achieved real security.” Ibid.

Lacking robust national savings, leaders of these Nations have borrowed heavily, often in foreign denominations to prime the pump of development, appeal to populist movements, or occasionally simply to line their own pockets.

The development never materializes, or a global crisis puts these nations at the end of a financial bullwhip and heavily indebted governments find themselves frozen out of global debt markets. The defaults begin and we are left with difficult questions about what it means for a Nation to be “broke” and the very nature of debt itself.

Countries Don’t Go Bankrupt

Walter Wriston, the innovative and influential Chairman and CEO of Citicorp in the 70s, famously declared that “Countries don’t go bust.” The aphorism has come to define how the international finance community treats sovereign credit. Wriston’s argument rested on the fact that a Country has its infrastructure, the productivity of its people, and its natural resources; its assets definitionally always exceed its liabilities. Professor Ross Buckley did not hold back in critiquing this Bankerly view of things in arguing for an international bankruptcy code:

Here speaks a man who clearly spent very little time outside the Northeast of the United States. Infrastructure, if a country has it, can go away-Latin America's crumbled throughout the 1980s as funding to maintain it simply was not available after the debt crisis of 1982. A people's productivity, if it exists, can go away, as educational systems fall apart or a disease such as HIV/AIDS ravages the nation's human capital. Natural resources, if they exist in meaningful amounts, can decline in value or the nation can lose the capacity to harvest, extract, or export them.

There is a more technical truth to it in that no formalized, global bankruptcy process exists for Countries. This is, as they say, “a feature, not a bug.” Lacking predictable outcomes, creditors extend financing beyond the point of reason, and like most debtors, Countries are all but required to take it to refinance older liabilities and keep the proverbial (and sometimes literal) “lights on.”

What we saw there [in the 1980s] was a period in which something like 25 countries defaulted. They defaulted because markets closed to them. And that’s what typically happens. The initial defaults in Poland and in Mexico made lenders very nervous. And when it came time to roll over the debt, there were no takers. That’s what's happening today. I mean, it’s almost an inevitable process. When things are good and money is easy, people pile in and the underwriters find plenty of buyers. But all of a sudden when one country defaults — let's take Lebanon, let's take Sri Lanka — everyone says, whoa, what about Country X and Country Y, Country Z? And then they become nervous. And then the debt can’t get rolled.

Newman’s perspective is an interesting one as a pioneer in what has pejoratively been referred to as “vulture funds.” Typically, countries offer bondholders new, longer-dated paper at a 50-60% haircut to what was originally owed. Many bondholders accept, either because they lack the resources to effectively negotiate or because it optically looks like a respectable recovery, but vulture funds leverage the legal system to push for a full recovery.

Unlike companies, countries cannot officially go bust so their creditors don't have the benefit of a clear insolvency framework. It comes down to what assets they can persuade a judge to “attach”, or deem subject to seizure. National sovereign-immunity laws protect many state-owned assets abroad, such as embassies. In America, however, stuff that is used for commercial purposes is fair game.

For funds like Elliott Management, where Newman plied his craft, this sort of nuance represents paydirt. Elliott’s most famous campaign against Argentina included attempts to confiscate a Naval destroyer as well as satellite launch sites.

It is certainly not revenge, even if we did not expect this matter to drag on for more than ten years. We are business people who demand what is common in business life: that the other side abides by contracts. And that if a contract is not fulfilled, an amicable solution is negotiated.

The Morality of Sovereign Credit

The moral high ground is a common positioning of creditors, either in the service of legal strategy or more commonly PR. Notions of the rule of law and a sense of morality around indebtedness color the descriptions these funds provide of their role in markets:

Where the debt forgiveness activists see poor countries in need of relief, Newman sees corrupt, deadbeat countries "dragging our legal system down by disregarding the rule of law." Newman and his colleagues simply reject the idea that vulture funds are extracting money from the coffers of the poor. "Debt relief advocates should recognize that the beneficiaries of debt relief are often corrupt or incompetent regimes that squander their nations’ assets and then cry poverty to avoid legitimate debts," says an Elliott spokesperson. "This cycle must be broken for countries to achieve economic development.

In his sprawling Debt: The First 5000 Years David Graeber points out the philosophical expansiveness of this view:

If history shows anything, it is that there's no better way to justify relations founded on violence, to make such relations seem moral, than by reframing them in the language of debt—above all, because it immediately makes it seem that it's the victim who's doing something wrong.

While creditors may point to pensioners as hapless holders of this debt, the true victims are the citizens who suddenly find their currency devalued and key public services suspended. There are also the salaries and pensions of public employees who often make up a large percentage of a nation’s workforce.

In the case of Puerto Rico, they have fallen into a large class of “Social Creditors” that lacking white shoe representation, must navigate a morass of bureaucratic indignities to file their claims, most of which get rejected for technical deficiencies.

More than 170,000 claims were filed in the bankruptcy proceeding, of which nearly 53,000 were related to salaries of public employees, such as Carmen’s, according to court documents. About 43,000 were for pension payments. In other words, more than half of the claims came from government employees and retirees.

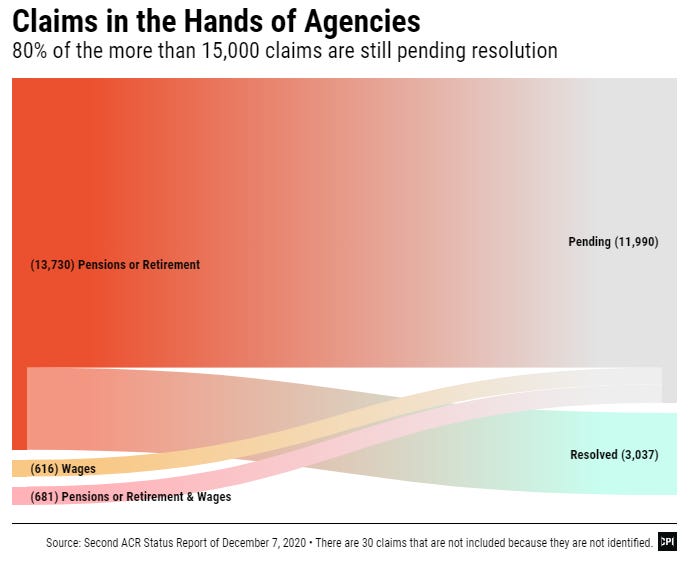

In the past year and a half, more than 60,000 of these claims have been disallowed and eliminated from the process, mostly due to technical deficiencies (such as incorrectly identifying the debtor government agency, for example) or for not providing enough evidence. Another 15,000 were transferred to several government agencies, where they are pending resolution in an administrative process of which few details are available.

- CPI

These creditors lack the resources of a firm like Elliott and in practice, their claims are not treated with the same conceptions around maintaining market integrity and “rule of law.” They are treated in the more practical and realistic view of credit which is that of classes, contractual obligations, and the cold technicalities of restructuring.

Their moral outrage may be more human, and certainly more legitimate, but it doesn’t serve the plumbing of global finance and so it's regarded as an unfortunate side-show of something much larger.

Destined for Crisis

If it seems like under this system we’re destined to be in perennial crisis, you’re right. Central banks are tasked more and more with absorbing the shocks and smoothing the ride. To do so they must maintain foreign currency reserves that themselves represent an opportunity cost in terms of economic activity. Fathimath Musthaq, a professor of political science, writes in A Permanent Bailout? for Phenomenal World:

In fact, central banks in the Global South have long used their balance sheets in normal times to absorb risk for the private sector. This is clearest in the accumulation of foreign-exchange (FX) reserves as an insurance policy against currency crisis, the single biggest threat to financial stability in the Global South. The 1990s and 2000s saw a series of currencies collapse under the weight of short-term volatile capital flows, from the South Korean won to the Turkish lira. Central bankers quickly learned that maintaining financial stability in a rapidly integrating world economy required currency management. This meant that central banks accumulate “war chests” of foreign-exchange reserves (see Figure 2), mostly denominated in US dollars, which they then use to manage the exchange rate via the sale and purchase of hard currencies. As with the Fed’s QE policy, reserve management works to improve central-bank balance sheets. And similarly, it reconstitutes the central bank as a market-maker bearing risk for an increasingly fragile, collateral-intensive, segmented, and yet globally integrated financial system.

This, like all modern expressions of debt, is about risk transfer, in this case from private balance sheets to public ones.

The transfer of risk from private balance sheets to the central bank’s has become a staple of modern finance. As is historically the case, the practice of central banking is far outpacing its theory. In practice, central banking appears to be converging on one goal: addressing market disruptions…Central banks in rich economies as well as in the Global South expend enormous resources in guaranteeing functioning financial markets by providing market liquidity through asset purchases. But we lack clear theories about what justifies this active and long-term intervention, particularly in noncrisis times.

Musthaq asks a critical question: If crises-style central banking is simply monetary policy de riguer now, what is the ultimate goal and what does it say about the stability and sustainability of our global, interconnected financial system?

Someone New at the Table

Everyone's at the table. Everyone's documents are on the table, except for China

- Jay Newman on Odd Lots

It’s not entirely fair to say China is “new” to the sovereign debt market, according to the IMF China has been active in international lending since the 1950s but its participation has ramped considerably since the launch of the Belt-and-Road initiative.

We find that the People’s Republic has always been an active international lender, even in the 1950s and 1960s, when it lent substantial amounts to Communist brother states. That is, official Chinese lending has always had a strategic element. What has made China such a dominant global creditor in the recent 20 years is the drastic increase of China’s GDP, combined with China’s “Going Global Strategy” to foster Chinese investment abroad, which was initiated in 1999. Chinese loans have helped to finance large-scale investments in infrastructure, energy and mining in developing and emerging market countries, with potentially large positive effects for growth and prosperity.

As the figure notes, this is a subset of China’s actual lending because no one knows how much lending China has done, or on what terms. Things that might be considered a “credit event” by the major rating agencies (Moody’s, S&P, Fitch) go unreported.

The “hidden debts” owed to China are consequential for debt sustainability in recipient countries and pose serious challenges for macroeconomic surveillance work and the market pricing of sovereign risk

Jay Newman, who may be getting a taste of his own medicine, speaking on Odd Lots about the opacity and scale of Chinese foreign lending:

The One Belt One Road Initiative has meant that China has provided money, either loans or investments in dozens of countries around the world, for ports, for rails, for communications, infrastructure, you name it, the Chinese are promoting it and lending money to developing countries. So China has become, and this is the critical element, China's a huge lender, an investor in developing countries, but no one knows how big they are. No one knows. I mean, the Chinese know, but no one else because the contracts under which they invest are secret. I've asked on many occasions to see a copy of these loan agreements. And it's always ‘shhhh, we can't talk about that. It's part of our agreement.’ And I don't think even the IMF has a clue what the scale of those investments are, which means that when you face a restructuring, you've got a creditor, a very aggressive and important creditor, China, which doesn't want to take a discount at all. So you have a super senior element there that we've never seen before in the history of EM lending.

Sri Lanka, Zambia, Cambodia, Kenya, and Laos are all facing debt restructurings with China serving as a reluctant cooperator with other Western creditors. While China has made suggestions that it will abide by the IMF’s “Common Framework”, the on-the-ground reality of debt negotiations has often been, in Newman’s words, “they're right and you're wrong. And they're implacable foes on many levels…” You need not be a Sino-conspiracy theorist to understand the implications of many of the world’s developing nations finding themselves financially beholden to China.

To Believe

Our relationship with debt is fraught, its implications nearly biblical. The original translation of the Lord’s prayer is “Forgive us our debts, as we also have forgiven our debtors.” The Latin root of credit is credere which means loosely, “To Believe.”

Graeber was inspired to write Debt after budget cuts the IMF led to Madagascar’s default and the subsequent human suffering as malaria prevention and other humanitarian aid went unfunded. Graeber in the Boston Review:

In the same way that the “ought” trumps all other values, debt trumps all other “oughts.” And I argue in the book that one reason why medieval theologians, whether Christian or Muslim, seemed so inherently suspicious about usury is because it creates a moral imperative that tends to trump all others. They recognized a potentially dangerous rival when they saw one, a moral system that would completely overwhelm their own if it was allowed full rein.

What we believe about the debt being issued today, especially debt that’s issued to developing nations has very little to do with their propensity or ability to repay. Rather we are in a state of perpetual mitigation and the belief that we are financing the transition to industrial modernity slowly fading.

The coming wave of sovereign defaults will crash in a multi-polar developed world already strained from cascading crises and a decade-plus of bail-out banking. Elliott and other distressed funds may have several more fat years ahead, privatizing the publicly funded assets of debtor nations. That is of course if they don’t find themselves like the Social Creditors of Puerto Rico, playing junior nuisance to a more tyrannical super senior in China.

You know, at Elliot we were extremely selective in the debt that we bought, because you really had to believe, you always have to believe when you're buying sovereign debt, that the debtor is capable of honoring its contracts”

- Jay Newman

Further

Jay Newman, now retired from Elliott, has become a novelist, drawing on his experience in global debt markets. His first book Undermoney is an international thriller about the dark money that sloshes around and influences our financial system.

An interesting player in the global debt market is the all-powerful rating agencies, which yield enormous influence over the borrowing costs of entire nations. Zsófia Barta writes about this in Rating Sovereigns also for Phenomenal World.

Just stumbled upon this one... Great piece.