From Investment to Savings

Private equity, private credit and the push for markets to "deliver retirement"

Summary

This week, American Affairs published an extended version of my Ouroboros piece. I support American Affairs’ mission to be “a forum for people who believe that the conventional partisan platforms are no longer relevant to the most pressing challenges facing our country.”

I’d encourage anyone interested in long-form commentary on industrial policy, cultural evolution, and political theory in America to consider subscribing. The quarterly print version is a high-quality journal worth saving or, ideally, passing along to intellectually curious friends.

The below is an abstract; paying subscribers can download a PDF of the entire essay below the paywall.

Last week Amit Seru, a professor of finance at the Standford Graduate School of Business, published an op-ed in the Financial Times urging private equity to be cautious in pushing for “retail” adoption of the asset class. In doing so, Professor Seru seemed to tacitly acknowledge the shortcomings of the strategy. It’s risky, illiquid, expensive, and, most importantly, free from onerous regulations like the Employment Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA). Seru writes,

Regulations such as the Employee Retirement Income Security Act and securities laws exist to shield retail investors from illiquidity and leverage risks. Private equity funds are currently not subject to Erisa unless retirement plan investments account for more than 25 per cent of total assets. More retail money could see funds cross this threshold.

Seru seems unaware that the proverbial fox has already found a side door into the henhouse via the annuity channel. In July of last year, I wrote about Apollo’s unique approach to insurance and how their merger with Athene represented a new era in the insurance market. Private credit grew rapidly even before the demand from increased annuity flows. However, the combination of stretched equity valuations, poor fixed-income performance, and higher yields made the perceived safety of annuities appealing.

My argument then, as now, is that supplanting traditional savings with an insurance product fed by credit created to meet retirees' needs upends a fundamental economic identity. In both Keynesian and Classical economic models, investment equals savings, and savings are forgone consumption. There is nothing wrong with choosing an annuity as a savings vehicle, provided the insurer matches liabilities with assets already in the capital markets.

Alternative manager-led annuities differ because they use the insurance balance sheet to originate de novo debt via the private credit market. The more annuity contracts, the more private credit assets must be originated. In doing so, asset-backed debt becomes a deep pool of potential credit origination, including consumer finance pools. In a dystopian end-state, savers might enter annuity contracts funded by their own levered consumption.

Even short of this, debt creation no longer follows equity in the traditional sense of allocating capital; rather, debt creation becomes a goal in itself. In the forthcoming Spring issue of American Affairs, I chart the longer history of retirement in America and how the credit-led annuity market is really the convergence of three secular trends: The end of defined benefit pension plans, the dominance of passive investing, and the ascendance of private equity.

Financial markets, ostensibly the mechanism for allocating capital to productive enterprises, have come to be viewed by investors, policymakers, and the public as vehicles for funding retirement.

It is telling that Seru specifically touched on ERISA in his FT piece. ERISA arose after several high-profile pension failures and began the march towards defined contribution retirement offerings. In trying to protect pensioners, ERISA ultimately created an entirely new market of financial product consumers.

In the drama of global finance, retirement savings play a minor but influential role. At the end of 2022, there were $40 trillion of retirement assets, with $27 trillion being held in public or private investment funds. According to research by J.P. Morgan, 72 percent of savers cite saving for retirement as their primary financial goal. Overall, the last decade and a half has been kind to savers as crises, both real and perceived, pushed interest rates lower and raised the value of all financial assets. With rates now rising, the starting valuations of most financial assets make the math of delivering retirement outcomes via traditional investing more questionable.

Whereas defined benefit pensions had assumed investment risk, defined contribution plans shift that risk to employees and, in doing so, create the perception that financial markets are savings vehicles. Investing is, of course, a form of savings. Still, for much of financial market history, capital allocation was carried out by active investment managers, bank loan officers, and others who carried the burden of identifying productive enterprises and avoiding value-destroying ones.

ERISA’s establishment of a fiduciary duty focused heavily on minimizing investment management fees, creating a regulatory moat for passive investment vehicles.

Absent a reliable ex-ante test for determining investment prudence, fees became the locus of adherence to the standard. This had significant implications for the investment management business. Price, as defined by fees, became the primary theater of competition among asset management firms. Passive strategies that aim to track an underlying benchmark became the default investment choice across retirement savings vehicles. These funds have the lowest expense ratios and, as a result, saw their assets under management explode as defined contributions and self-directed retirement vehicles came into prominence. As of November 2024, passive investing makes up over 50 percent of global equity mutual funds and ETFs.

A debate rages about the influence of passive investing on price discovery, but what is not debatable is that passive investing significantly impacted the margins of the asset management business and created a handful of dominant firms whose assets are overwhelmingly managed in passive strategies.

Innovation in asset management took the form of “alternative investments,” of which private equity was the primary expression. The fallout of the Global Financial Crisis simultaneously made private equity's optically low volatility look even more attractive, while the monetary response of low rates boosted the value of their assets. At the same time, banking reforms created an industry of non-bank lenders that specialized in lending into the rapidly growing private equity market.

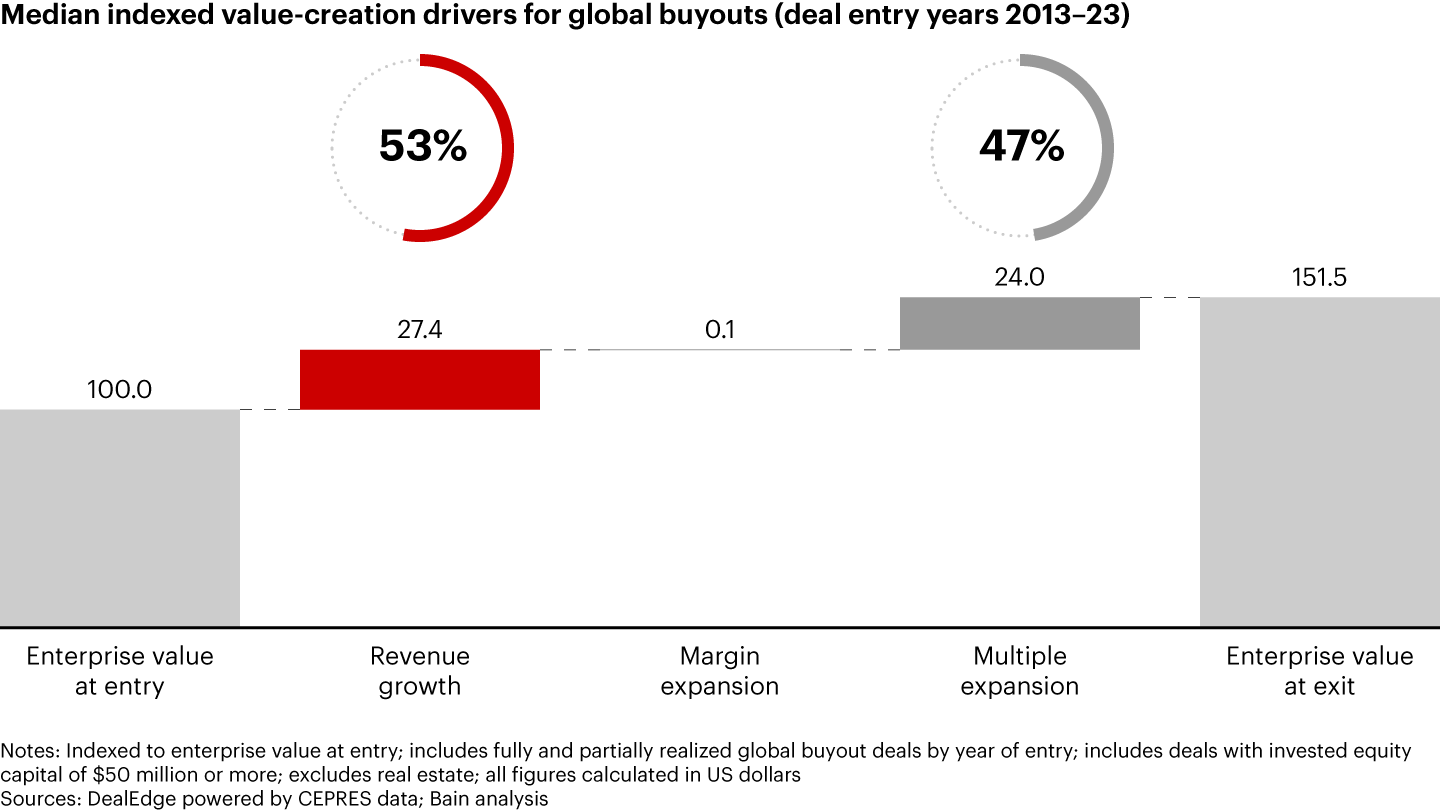

Multiple analyses show that nearly half of the private equity returns come from multiple expansion, not a fundamental business improvement. When multiples stopped rising, private equity leveraged company cash flows for dividend recapitalizations, adding debt to generate returns.

Private equity is now struggling to return capital to their LPs (mostly pensions and endowments), constraining new fundraising. When debt markets became less amenable to dividend recaps, private equity began putting the assets on the balance sheet in hock, structuring asset-backed paper that could be distributed to different pools of capital. Perhaps annuitants can squeeze a few more drops from the dirty sponge.

This focus on collateral lending, as opposed to productivity or repayment ability, is another sign of runaway demand for debt securities. It conflates funding with wealth creation; the goal of debt becomes a form of asset capture versus productivity or growth. This is driven by a demand for return without accompanying risk, exactly the kind of investment that prospective retirees seek when they enter an annuity contract.

In fairness, annuities are still a tiny part of the global market pie. If rates stay sustainably higher, annuities may maintain their popularity, but if a prolonged recession or exogenous shock were to reset asset prices, savers might again be willing to assume more traditional risks. Right now, outside of acutely speculative markets, there seems to be a general unwillingness to take equity risk.

Under this model, equity exists to serve the creation of debt. Resource and capital allocation are not front and center. This form of finance values greater origination volumes both to support asset prices and to feed new assets into the top of the insurance balance sheet. This system undermines the simplistic belief that the capitalist system works via the capital allocation feedback mechanism. Instead, the self-perpetuating demand for debt instruments continually supports asset prices…Without credit contraction, asset price reckoning is forestalled. This reduces the theaters of speculation to corners of the market without debt‑driven asset prices—cryptocurrency, venture capital, and a smaller cohort of traditional equities.

I won’t claim to know where all of this is heading. There is an impulse driven by GFC muscle-memory to predict some sort of fallout, or “Minsky Moment,” but the reality is that risk is far more diffuse than either the GFC or the Savings & Loan Crisis. Should the primacy of debt in financial markets continue, I think a more likely path is that returns across the capital stack gradually degrade as malinvestment proliferates.

With long-run domestic GDP growth of 3%, everyone seems to be underwriting 6-8% nominal investment returns. What’s unclear is where all these pockets of high-value-added economic activity are taking place. Could the marginal productivity of this new debt really be greater than one? Or are we just slicing, dicing, and structuring secularly shrinking real returns? Running in place may be sufficient for those on the cusp of retirement, but for everyone else… devils take the hindmost.

Paying subscribers can download a full PDF of the American Affairs essay below the paywall.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Lewis Enterprises to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.