Interdependent Nation

Prescient warnings in Felix Rohatyn's "America's Economic Dependence" for Foreign Affairs (1989)

Our basic weakness is due to excessive levels of debt, both in the government and private sectors. This affects every aspect of our policies.

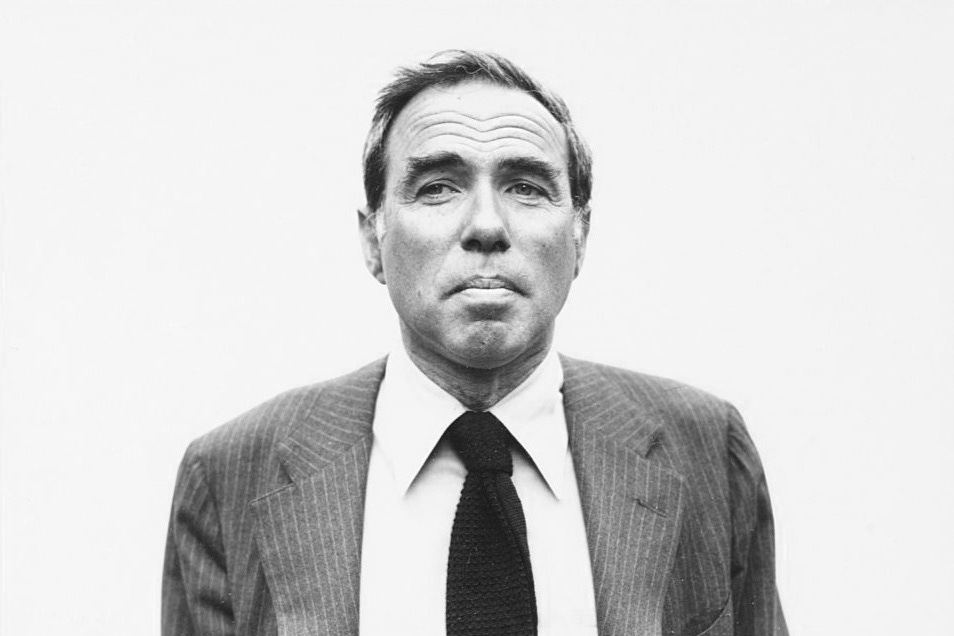

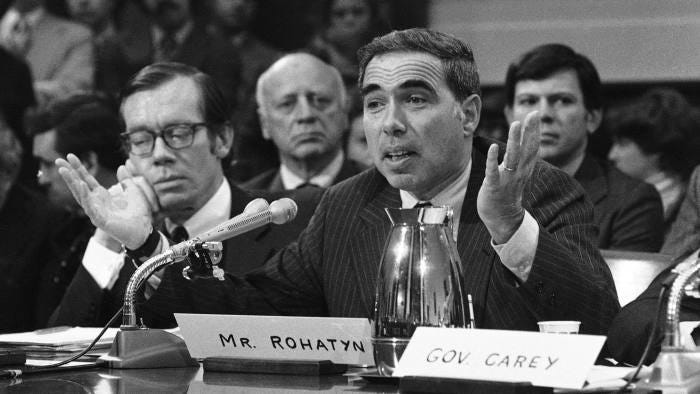

Felix Rohatyn

This month it was announced that wonk-cum-banker Peter Orszag will take the helm at Lazard. Orszag is an economist who has worked in academia, government, and the private sector. He served as the Director of the Office of Management and Budget under President Barack Obama, and was also a key figure in the development of the Affordable Care Act. Prior to his work in government, he was a professor of economics at the University of California, Berkeley, and a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution.

This a timely choice as the US is finding its international preeminence coming into question, a political shift away from globalization is taking hold, and a fiscal and monetary conundrum. Such a setting provides good reason to revisit the work of another Lazard leader, Felix Rohatyn, and his 1989 Foreign Affairs essay “America’s Economic Dependence.”

The bankers of Lazard have tended to be more like financial diplomats. Andre Meyer, Lazard's leader from 1940 to 1977, served both Kennedy and Johnson and was pivotal in setting up Third World development banks. Steven Rattner of the Auto Task Force and a semi-public figure through the mid-aughts also briefly led the firm. Always ahead of its time in terms of a global footprint, Lazard played a role in the financing of the Panama Canal and has maintained its role as a key advisor to sovereigns in debt restructurings. Felix Rohatyn, a Meyer protégé, helped restructure New York City’s dire finances by serving for two decades as the Chairman of the Municipal Assistance Corporation before becoming ambassador to France.

“I get called when something is broken…I’m supposed to operate, fix it up, and leave as little blood on the floor as possible.”

Rohatyn’s predictions have had more resonance than his admonitions. When he wrote in 1989, the end of communism as a serious ideological threat to liberalism was apparent but the Berlin Wall had not yet fallen. The Latin American debt crisis had roiled markets throughout the 80s but the Savings & Loan crisis had not come to a head. Most importantly the details of how society would be organized post-Cold War had not come into focus, and the role the US would play in this new world was unclear. Rohatyn begins,

Will that world be chaotic or orderly? Will there be growth or stagnation? Will the United States be able to play the preeminent role that it played in this century? This is the context in which we must examine the present.