Hippocratic Capital Allocation

Systems designed to avoid regret often produce It

Many dogs resemble their owners in either visage or disposition, or so the old trope goes. The psychological implication is that we are attracted to things that reflect our image, or more precisely, reflect the image we hold of ourselves. Portfolios and the investors that manage them share a similar phenomenon. The short-seller sees themself as a truth seeking maverick, the growth investor as having a prescient view of the future, and the value investor as being similarly undervalued and overlooked as the names in which they traffic.

There is nothing inherently wrong with this. Feeling deeply connected to a core motivating force is a prerequisite for doing any good work. Of course, investing as a vocation requires a certain cognitive dissonance. Successes are easily chalked up to good fortune, while failures must be attributed solely to error or misjudgment. To suggest that the entire enterprise were merely dictated by chance would undermine its pursuit.

This year, I have been considering the attributes that make a good investor. I have also been considering the station of everyday people who feel no intellectual connection to markets, but who nonetheless must make investment decisions as part of their effort to secure financial and material comfort. What constitutes prudence in a world in which the imprudent seem to experience more good fortune than the prudent are rewarded to for their piety?

Confidence and curiosity

Whether you manage capital for clients, your kin, or simply yourself, confidence and curiosity seem to be the prerequisites for success. Confidence expresses itself not in where you choose to invest your efforts, but in the areas in which you confidently ignore. Is the balance of capital tilted heavily in favor of those who watch each Federal Reserve meeting with bated breath? I would posit it is not. Is investment Valhalla on the other side of the next two-hour podcast? Were it so simple!

Curiosity is confidence’s foil. You must be voracious in your desire to understand the world, but judicious in believing that you can make tractable or actionable what you learn. Curious inquiry is the most speculative activity any investor undertakes. You set off down trails that may require backtracking, you collect intellectual scrip of uncertain value, and you plant seeds in infertile soil hoping to return to some green shoot in the future. And it is confidence that empowers you to turn around, to mark your scrip to zero, or to till the soil of your work for another day, month, year.

Doing less, by doing less

In 2025, I have made perhaps the fewest active investment decisions of my investing life. This is partially a function of circumstance and partially a conscious choice to determine the minimum effective dose of focus on capital allocation. That has, in turn, led me to consider the so-called “average saver,” the type of investor who only sees a Financial Times in the lobby of a hotel, who must make an investment decision once per year, or perhaps only when they change jobs.

I have watched as professionals consult ChatGPT on what their 401(k) investment elections should be. I have seen young, front-line workers allocate 100% to stable-value funds outpaced by inflation since inception. What do these portfolios say about the investors managing them? They are certainly neither confident, nor curious.

Their understandable disinterest in markets is placated by an industry all too eager to shoulder the complexity for a nominal fee. Dressed in the language of institutional prudence, asset managers take a Hippocratic approach to these clients, protecting the most extreme downside scenarios using relatively rudimentary heuristics about risk and return. The do-no-harm portfolio is typically a target-date fund (TDF) with a dynamic allocation that (theoretically) reduces risk as the hopeful retiree approached retirement age.

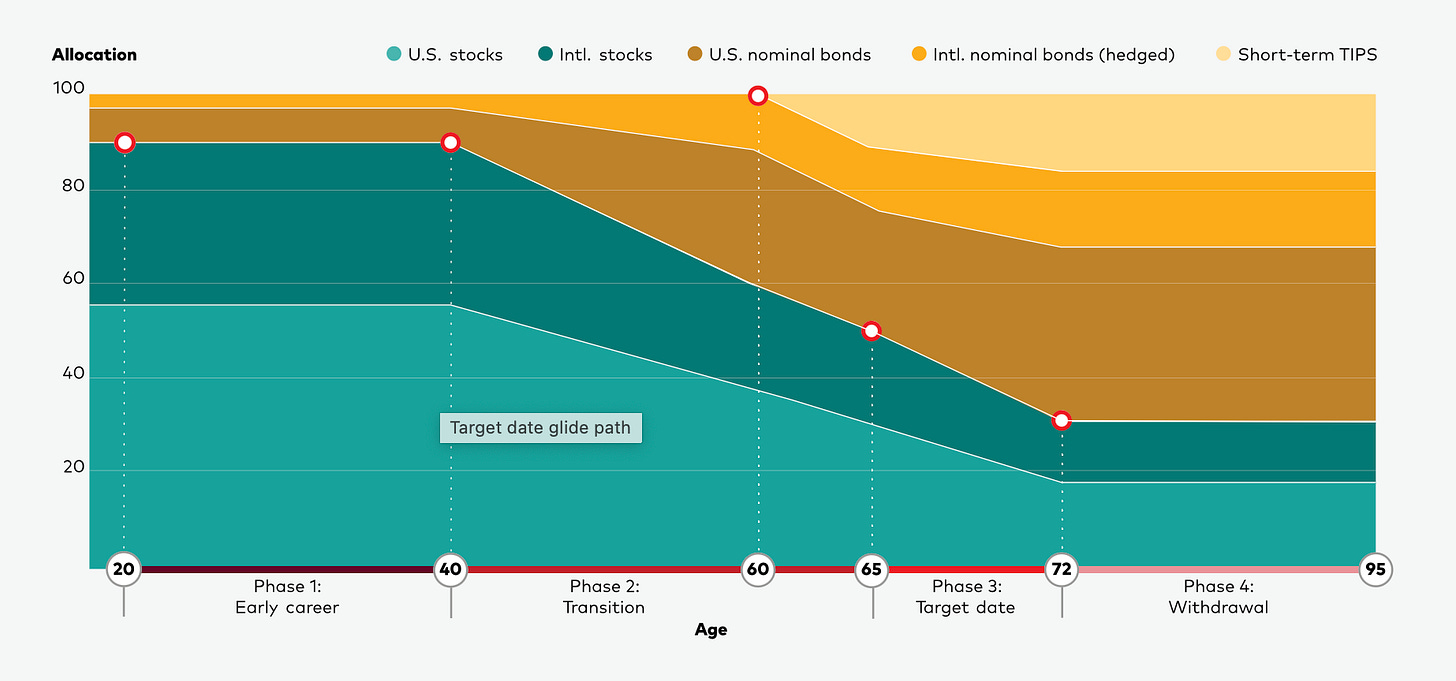

Consider, the Vanguard retirement glidepath, which logically starts you off overweight to equities, even a large allocation to international equities and then, rather abruptly, after age forty starts aggressively buying bonds.

The only input to this investment strategy is your birth year, which is entirely exogenous to markets or relative value. Did equities take it on the chin like they did in 2022? Doesn’t matter. If you are over fifty, you are buying less of them. Did rates rally such that long-term bond yields were less than 2%, like in 2021? Doesn’t matter, you are buying more of them with every paycheck. Why does a person who happens to be forty in a given year need to start selling down the international stock exposure that was additive just 12 months prior?

To my question of an appropriate level of focus on capital allocation, is one’s birth year sufficient data for making investment decisions? I don’t believe it is, and in 2005 as target date funds were beginning to chart their journey from innovation to default option, Alliance Bernstein (AB) came out with a report saying as much. AB concluded,

“It takes a lot of equity to generate sufficient growth. Our analysis of historical US stock and bond data shows that the conservative and moderate equity allocation…were likely to generate enough growth to fund spending for only 15 or 20 years. Over longer time horizons, their success rates dropped precipitously…While a classic measure of risk in investments is market risk, measured by the standard deviation of returns, we demonstrate that a myopic focus on this measure of risk is inappropriate for addressing the retirement-savings problem. Broadly speaking, risk for these funds is the likelihood of failing to build enough savings to fund spending throughout retirement.”

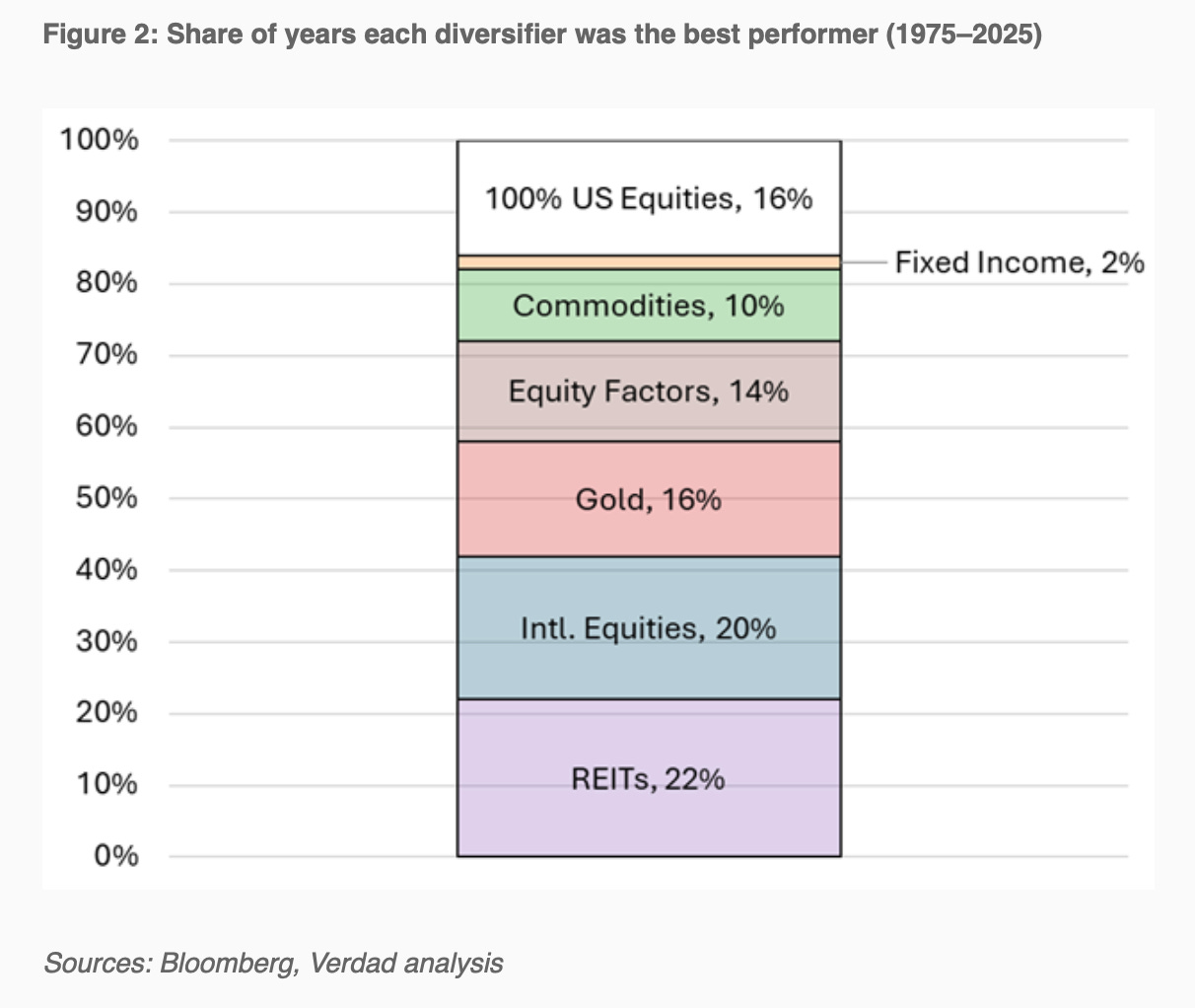

AB took the time to do a lot of math and backtesting to conclude that returns are, in fact, a function of risk, and turning risk exposure down too quickly can have disastrous impacts on actually being able to comfortably retire. As an aside they also found that REITs have an enormously beneficial impact on retirement outcomes overtime, but I’ll leave that for another day.

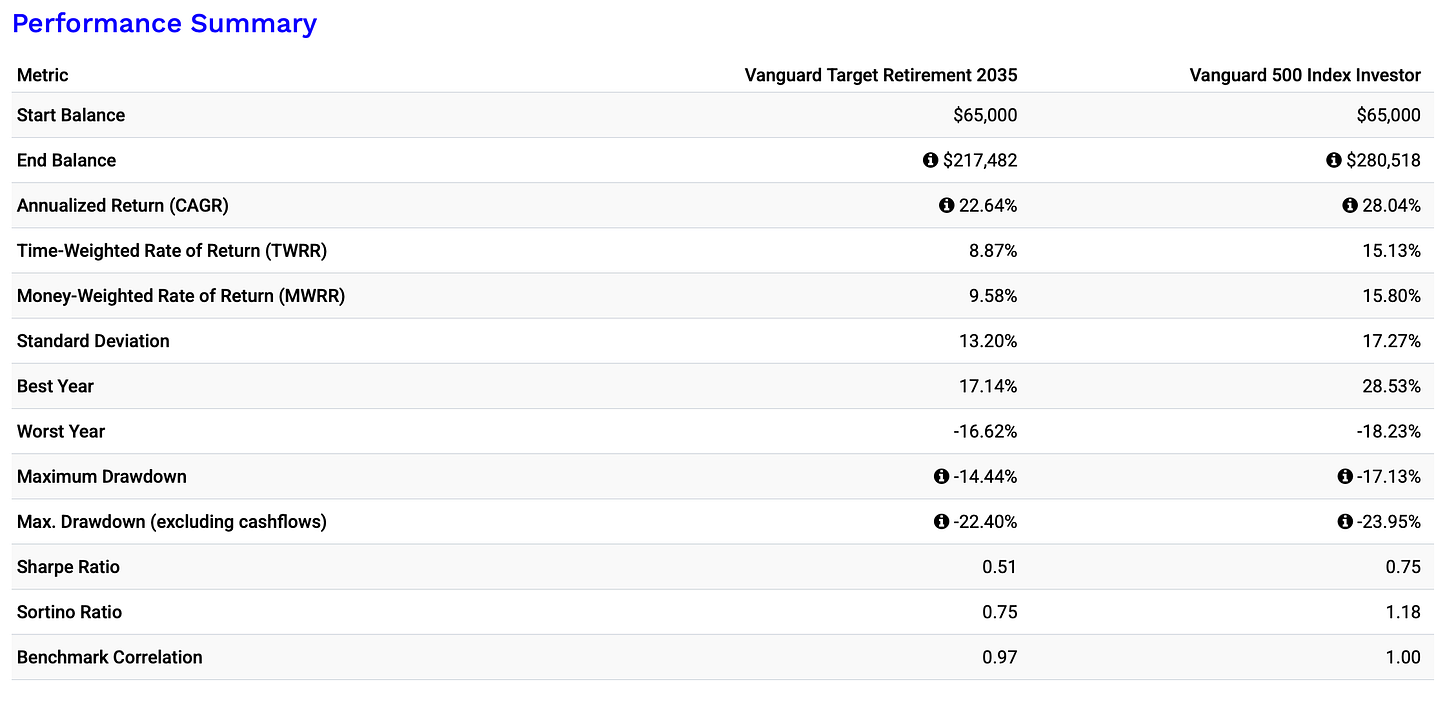

If you were 50 in 2020, the qualified-default investment options (QDIA) was likely to be a 2035 target date fund, perhaps even Vanguard’s. Assuming you have diligently contributed every month over the past five years, increasing your contributions at approximately the rate of inflation, your dollar-weighted annualized return has been 9.58%.

This is a respectable return, and I’m not going to suggest that a fifty year-old should continue to white-knuckle an increasingly less diversified index. During the emergence of the TDF, proponents tacitly admitted the returns would likely suffer. But, they argued, that the smoother ride of ramping bonds as a participant approached retirement would prevent some of the behavioral pitfalls of the reluctant investor. Namely, selling low and buying high.

Unfortunately, the downside protection offered by increasing bond exposure was pretty minimal, the worst year was only 160 basis points less bad, and the worst drawdown just 150 basis points better. Are we to believe that the investor who would have bailed down 23%, held steady at down 22%?

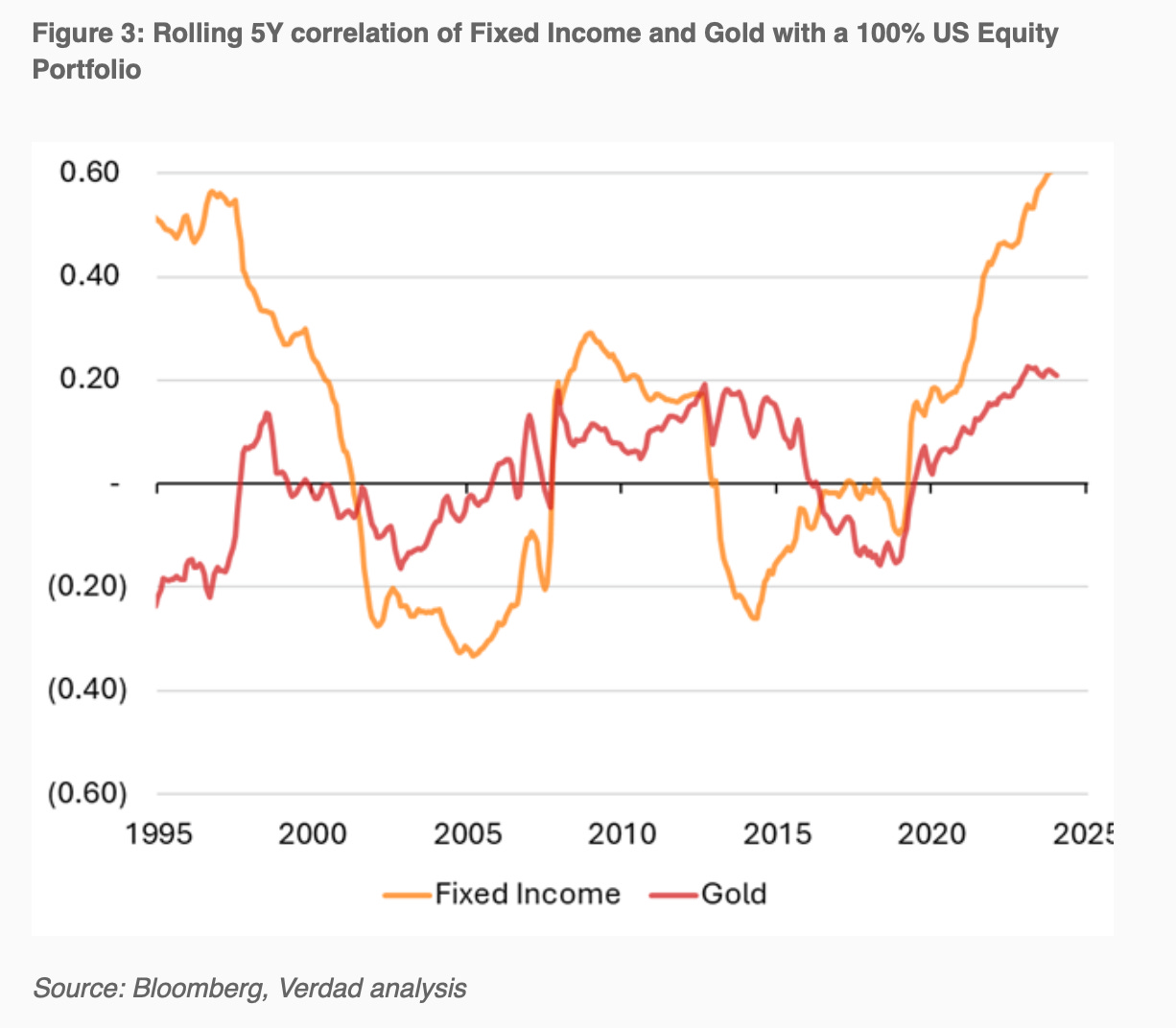

This is partially a design problem. Bonds, despite their reputation, are not a diversification panacea. As the team at Verdad Capital shows, the relative diversifying benefits of fixed income actually vary considerably.

More importantly, there is no single asset class which can reliably reduce volatility. The impact, as seen above, is periods where increased fixed income allocation simply lower returns without a commensurate reduction in exposure to market risk.

Since its inception in 2003, when our hypothetical retiree would have been 33, the Vanguard 2035 fund has an annualized return of 7.96%, versus around 11% for the S&P 500. Again, the point is not that 100% equities is a viable alternative, it’s that the conservative glide path has reduced returns without significantly reducing market risk.

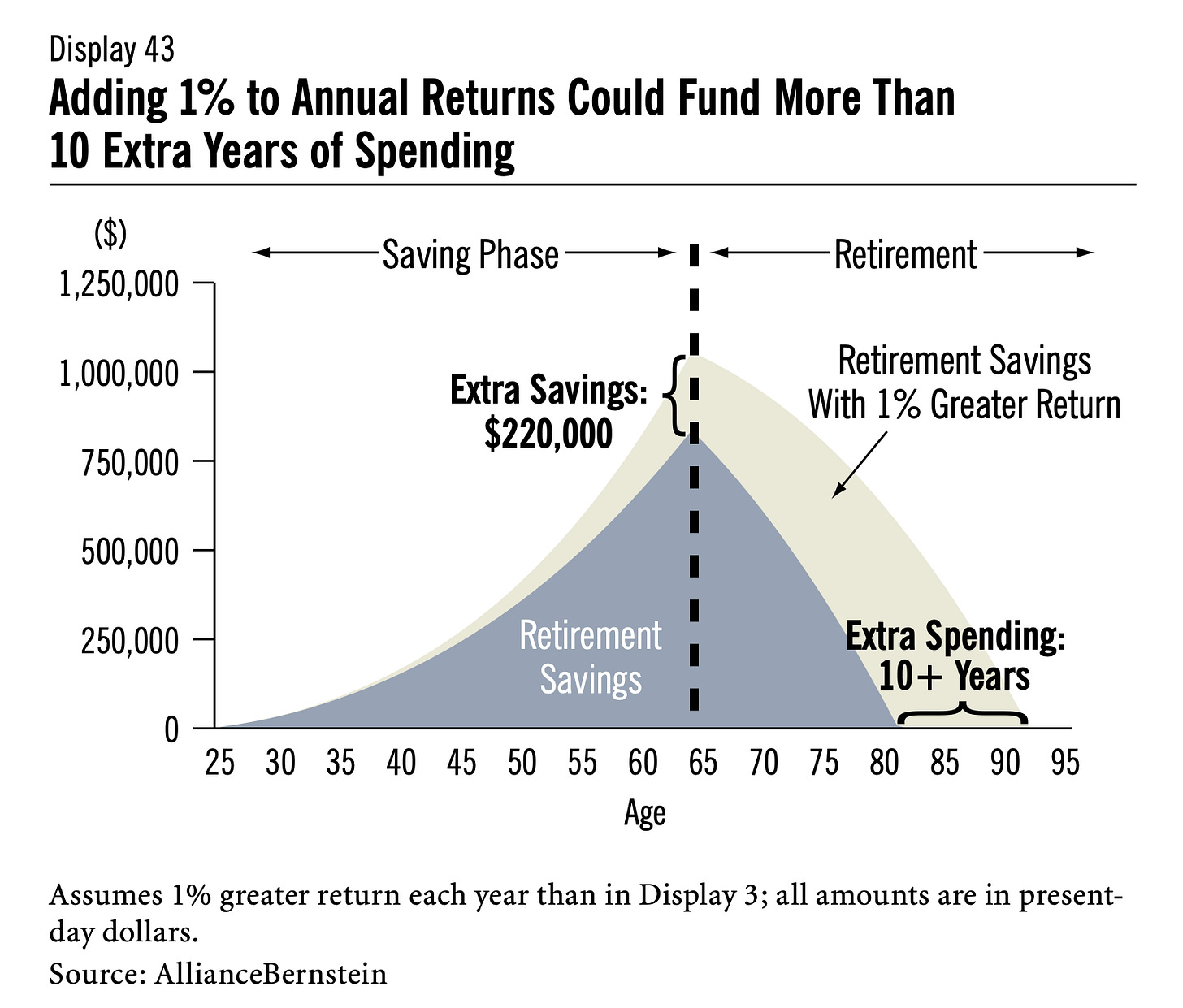

AB finds in their analysis that, “[w]hen the investment horizon is very long, small differences in return can make a huge difference: Adding one percentage point to annual returns could provide over 10 more years of spending. Thus, target-date retirement funds should seek extra return wherever possible.”

Failing to meaningfully reduce market risk, the TDF has also significantly increases longevity risk (living beyond one’s savings) and inflation risk for the participant.

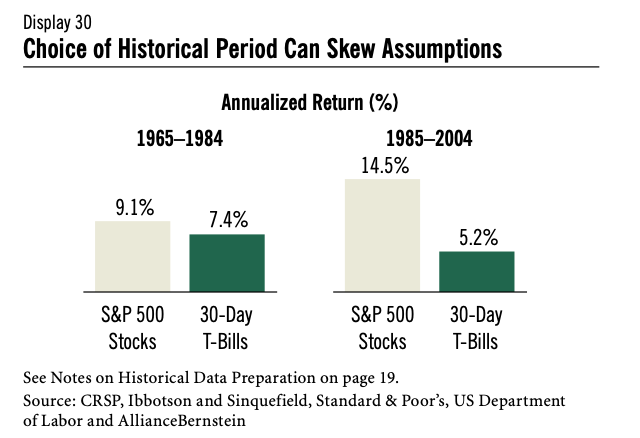

The quantitative justification for the TDF and its strategy is based on a pretty limited data set when considering the length of the investment horizon. Since 1960 there have only been two, distinct, non-overlapping 30 year return series, 1960-1989 & 1990-2019. There are 421 overlapping 30-year periods since 1960 if you calculate on a monthly basis. Monte Carlo analysis is used to fill the data gap. But that falls prey to its own biases. AB demonstrates the selection of data can have huge implications for asset allocation.

“If we had employed a static return-generation approach 25 years ago, using return data from 1965 to 1984, our assumptions might have called for nominal S&P 500 stock returns of just 9.1% per year and cash returns of 7.4%! These assumptions would have served as a poor basis for modeling returns in the subsequent 25 years, when the S&P 500 returned 14.5% per year versus 5.2% for T-bills.”

Despite this, the TDF sets you on a path that doesn’t vary. When the facts change, your TDF does not. Explaining why this product persists in its enviable position of being the regulatory default selection for reluctant investors depends on your level of conspiratorial thinking.

It could be that the TDF allows an asset manager to stuff multiple fee bearing products into one. It could be that avoiding the worst case scenario at the expense of returns actually stabilizes asset-based revenues and growth. More nefariously, it could be that having a demographic wave of price insensitive bond buyers has political benefits even as their retirement security slips out of reach.

Engaged stewardship as prudence

Has this lengthy discussion merely been a vehicle for my diatribe against traditional retirement planning? Transparently, yes, but it also shows that the cost of prudence, of doing nothing in service of doing no harm, carries real risk of its own. If your aims are to build wealth in financial markets, or even merely to achieve financial security through asset appreciation, average returns will not suffice.

Whether you are reluctant investors or an active one, understanding that above average returns will require above average risk, how do you manage your savings effectively? Sadly, there is no formula, no automated process for ensuring success.

The speculative fervor that retail investors have displayed recently, whether in traditional, crypto or prediction markets, have demonstrated some sort of intuitive rejection of the prescribed path of prudence. Perhaps, this is not such a bad thing.

Prudence, as it is commonly practiced in modern portfolio construction, has come to mean minimizing visible error rather than maximizing lived outcomes. In this framework, volatility is treated as risk itself, and judgment is deferred to heuristics that are easy to defend, if not particularly effective at funding retirement.

A more engaged model of capital stewardship—by institutions, professionals, or individuals—would almost certainly produce a wider range of outcomes. Some investors would fare worse. Many would fare meaningfully better. Markets have always compensated those willing to endure uncertainty in pursuit of growth, and long-term capital formation has never been a low-variance exercise.

What is required is not constant activity nor prescriptive formulas. Rather an understanding of what one owns, why one owns it, and when those reasons no longer apply. Stewardship accepts uneven paths and variable outcomes.

This view of stewardship is admittedly difficult to scale. Judgment does not compress well, and engagement cannot be mass-produced. Perhaps active management is due for a comeback. Regardless, our current model of treating long-term investing as a solved problem will come to be increasingly questioned.

When investors’ portfolios reflect their own confidence and curiosity markets tend to function better. Capital is allocated with intent rather than inertia, prices incorporate a wider range of views, and risk is borne by those who have consciously chosen to bear it.

Defaulted investment, by contrast, concentrates behavior, suppresses information, and turns markets into reflections of policy design rather than underlying economic reality. While engagement may introduce more dispersion in outcomes, it also restores the diversity of judgment that allows markets to discover value, absorb shocks, and reward long-term thinking. Ultimately, an investment system organized around avoiding regret is likely to produce it.

Reminds me of Victor Haghani and actively sizing risk allocation overtime based on risk premium being offered, versus using a static asset allocation.

Wonderful. I sometimes get a stiff neck after nodding so hard in agreement with you.