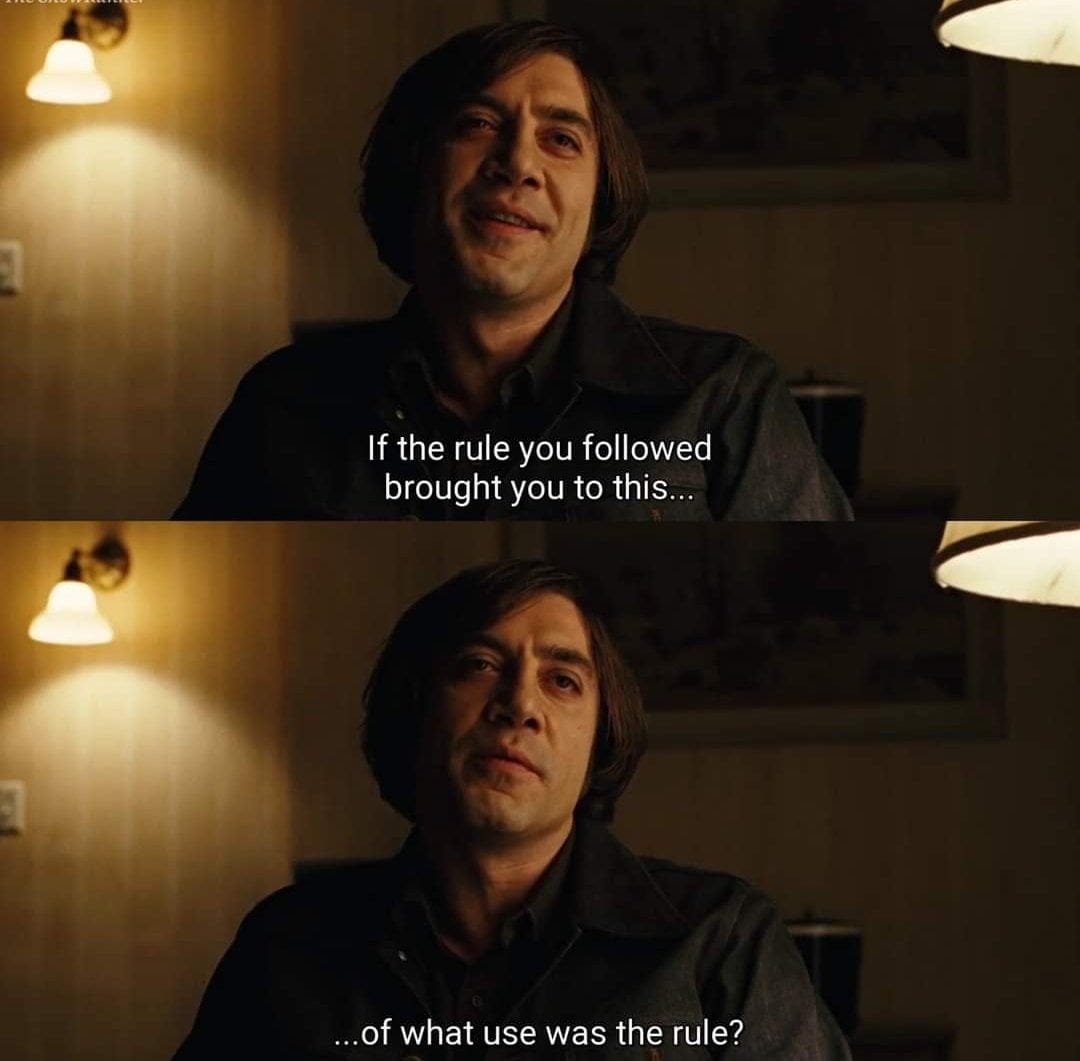

Somewhere you made a choice. All followed to this.

- Anton Chigurh, No Country for Old Men

It could have been when the Fed bought high-yield bonds in 2020 or quantitative easing following the Global Financial Crisis. It may be as far back as the 1999 Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act or the Telecommunications Act of 1996. It could have been developments beyond our control, like China’s ascension to the WTO in 2002 or as far back as the Berlin Wall coming down. At each moment, we took a turn further toward the way of organizing the world most of us are now accustomed to. It was, and is, a historical aberration. A world where the free flow of capital meant that peace among superpowers was maintained by the tensions of highly integrated trade has never existed at the scale achieved over the last 40 years.

Corporations, increasingly driven by shareholder primacy, redirected investment from domestic production toward global supply chains and financial engineering. This architecture generated substantial aggregate wealth but distributed it with growing inequality. The availability of ever-cheaper imported goods alongside the distribution of high-speed broadband and mobile telephony offset middle-class wage stagnation. These forces, once celebrated as engines of prosperity, now reveal themselves as architects of the very instability they were meant to prevent.

When President Trump unveiled his hastily assembled posterboard with effectively arbitrary tariffs, far more severe than anyone (perhaps even their author) expected, that way of organizing political and economic life ended. In the following week of tumult, when the harshest version of the policy was eventually downgraded or delayed, many intelligent writers and analysts opined. They have crunched the numbers, been apoplectic about the recklessness, and applied all manner of game theory to attempt to make the unintelligible intelligible. I have no interest in rehashing those exercises here. Instead, I wish to explore the collective delusions about our economy and its future revealed by this episode.

The central question is not whether Trump's tariffs are economically optimal—they almost certainly are not—but rather what their implementation reveals about the fragility of our economic consensus.

The first delusion is that Trump’s extreme trade policy differs from any other exogenous shock to the system that could have arisen in such a highly levered and geopolitically tense environment. We would be in nearly the same place today had China invaded Taiwan, or if the EU had become more fractured, or if Russia made another military overture.

Protectionism was growing, and any number of developments would have accelerated its more extreme forms. It may feel different since the spark was an admittedly ham-fisted policy unveiling from the leader of the Free World. Still, practically speaking, it was always going to be something that eventually cracked the reign of globalization.

The Cargo cult mentality that technocratic competence could overcome growing unrest hid a surfacing crisis of faith. Brexit, the growing popularity of far-right politicians in Europe, and of course, the heavily lopsided election in the U.S. were all directly counter to the perceived universal acceptance of liberalism and free trade. These political shifts were only tangentially and often wholly unrelated to trade.

In fact, the second such delusion is in narrowly defining trade as the central issue. Trade has been a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for the divide in perception between growing economies and stagnating social mobility. In 2023, the FIRE sectors (Finance, Insurance & Real Estate) contributed more than 20% of value-added GDP, while professional services added another 13%. This has famously corresponded with a decline in manufacturing, which has fallen from 20% of GDP in 1980 to less than 10% today. While much of the public messaging around trade has focused on restoring American manufacturing, shrinking the FIRE sectors, and “rebalancing” corporations are the more immediate and salient impacts.

As Russell Napier points out, the world fell into a monetary and trade system imposed from abroad,

“When interest rates appear to be permanently depressed relative to growth rates, asset valuations rise, leverage increases, and investors are incentivized to pursue gain through rising asset prices rather than through investment in new productive capacity. The decoupling of growth and interest rates was driven by the People’s Bank of China’s (PBOC) appearance as a non-price-sensitive buyer of U.S. Treasury securities, and indirectly by the role China’s excessive fixed-asset investment played in reducing global inflation and hence interest rates.”

In the U.S., the most successful companies have pursued high-value-added services or business models that extract rents from intellectual property, moving actual production to progressively cheaper geographies. In the blackboard understanding of free trade, “the winners win, more than the losers lose.” That understanding is based on the belief that the availability of cheap goods is more than ample compensation for the loss of social mobility or security through traditional employment. For most economists, cheaper goods and higher consumption are values in themselves.

The expansion in the U.S. has been driven by hyper-profitable firms that require relatively fewer employees, driving up productivity but at the cost of economic dynamism that spreads those gains more broadly. The economies of Ghana and Germany wrestle with unique issues of their own, but they represent the two sides of globalized trade. Ghana is a Ricardian dream of specialization and enjoys lower unemployment and a higher GDP per capita growth rate than Germany's. Germany’s economy is more diverse but sub-optimal in the traditional understanding. Ghana is unlikely to ever Westernize or become a functioning social democracy. Nor will Germany ever be able to fully capitalize on the innovations its diverse, complementary industries may generate. The populations of both find themselves in perpetual malaise.

The U.S. economic schema has become an amalgam of the two. With a concentrated economy primarily focused on finance, services, and software, the US has experienced the same free trade “wins” of low unemployment and GDP growth. Like Germany, it has benefited from access to low-cost goods manufactured elsewhere. And, like Germany, its politics have moved further to the right, rejecting little by little the policies to which elites credit its abundance.

The wonks consider these populations rubes, simpletons taken with populist rhetoric. A more rational explanation is that free trade's “winning winners" simply got too concentrated in a few industries, specifically a few geographies. Eventually, the larger population no longer felt that the benefits of cheap goods were adequate compensation for their declining employment prospects and growing economic precarity. The same statistical aggregates that economists celebrate obscure experiences of citizens increasingly alienated from globalization's promised benefits.

The fundamental conflict the current trade disruption exposes is between efficiency and resilience. We prioritized efficiency through global specialization for decades, creating complex, interdependent systems that maximized short-term economic gains while introducing systemic vulnerabilities. The pendulum is now swinging toward resilience. The messier, costlier arrangement in the short term but potentially more sustainable in an era of mounting geopolitical tensions and social unrest. This rebalancing will be painful and disruptive, challenging the primacy of shareholders and forcing a reconsideration of how economic value is created and distributed.

Tariffs, as currently conceived, aren't a complete solution to our economic imbalances, but they do directly challenge the conditions that have allowed specific industries to flourish disproportionately. While I don’t expect any of the promised gains for Main Street anytime soon, the specter of upended trade will change corporate investment patterns. Just as COVID inspired a re-jiggering of supply chains that continued long after the immediate impacts of the pandemic subsided.

Many have suggested that uncertainty will freeze investment capital required for corporate rebalancing into productive asset development. Perhaps, but policy volatility tends to be directional, so while the exact breakdown of tariffs and the carve-outs remains to be seen, corporations have undoubtedly gotten the message that we have taken a decisive turn away from the unfettered march of globalization. Just as the seemingly disparate policies of the 1990s and early 2000s created a progressively more integrated world, tomorrow’s policies will walk us back from it.

The reconfiguration of global trade will inevitably produce outcomes that defy our current projections. While protectionist rhetoric often evokes nostalgia for mid-century manufacturing dominance, replicating developing nations' manufacturing capabilities would be economically unviable and strategically misguided. The goal is not to turn back the clock but to catalyze new forms of productive investment better aligned with America's existing capabilities and future needs. Economic disruption has historically been the crucible in which innovative business models and technologies emerge.

We may see the emergence of advanced manufacturing ecosystems centered around critical technologies such as semiconductors, biotechnology, clean energy infrastructure, and defense-adjacent industries. We might witness investment in currently undervalued domains such as infrastructure modernization, housing development, and regional economic diversification. Or we may not, but it was abundantly clear that the existing paradigm would never deliver them.

Perhaps the most profound irony of our economic moment is that the dogmatic adherence to free trade principles has sown the seeds of its own rejection. By elevating economic efficiency above all other considerations, the architects of globalization dismissed legitimate concerns about social cohesion, community stability, and national resilience as parochial or misguided.

This intellectual hubris bred a dangerous disconnect between policy elites and the citizens who experienced globalization's dislocations firsthand. Over time, this disconnect fostered a deep skepticism toward expert opinion and institutional authority, creating fertile ground for political movements that promised to upend the system experts insisted was optimal.

Economic systems ultimately require social and political legitimacy to endure. Western liberal economies benefiting from or even relying upon the innovations, labor, or resources of authoritarian or communist states is an obvious incoherence. Trump's tariffs represent not an aberration but a predictable culmination of contradictions built into the globalized economic framework.

For decades, the neoliberal order rested on tenuous contradictions: democratic legitimacy alongside increasingly concentrated economic gains, national sovereignty alongside borderless capital flows, and domestic stability alongside perpetual creative destruction. It operated on borrowed time, sustaining itself through elite consensus, institutional inertia, and the absence of viable alternatives. This system maintained credibility only as long as its broader benefits remained visible to the average citizen.

The panic, the bargaining, the anger—it was always going to be this way. What we witness now is not a temporary deviation from an optimal economic arrangement but rather the system's internal logic reaching its natural conclusion. Despite a decades long effort to silo them, markets ultimately require public consent to function.

Of all the pieces I've recently read trying to make sense of the world right now this is probably the best. Economist and WSJ please GTFO here.

Excellent work