Free to Choose

Review and Reflections on Jennifer Burns's "Milton Friedman: The Last Conservative"

“Milton Friedman’s misfortune is that his economic policies have been tried.”

― John Kenneth Galbraith

Most people are familiar with Milton Friedman in one way or another. Either they were exposed to his ideas through his ten-episode PBS special that presented a distilled gospel of free markets, have seen the perennially viral Phil Donohue interview, or, like me, were taught Friedman’s ideas in a high school or college-level economics class. Regardless, Friedman and his high-profile proselytizing have largely shaped the political economy of the past 40 years.

In some ways, I am a hostile reader of a Friedman biography. My professors did not teach his ideas as theoretical frameworks, opting instead to convey a sense that they were Natural Law. Those sufficiently indoctrinated by this approach find themselves befuddled that our world consistently undermines these beliefs. They view modern markets as corrupted aberrations of the perfect system Friedman sought to define. For everyone else, the experience of private, non-academic life quickly reveals Friedman’s ideas to be useful but impractical reductions of the complexity of economic organization.

As a result, Milton Friedman, who died in 2006, has become somewhat of a pinboard for ideas that are merely proximate to his theories. As The Economist aptly put it,

"Much as the three Abrahamic religions lay claim to one saviour, conservatives, libertarians, and classical liberals all claim Friedman."

Today, Friedman is more an avatar of a broad notion of economic conservatism. While he is undoubtedly a giant in the field, his enduring legacy is installing the primacy of monetary policy. To extend the religious metaphor, mainstream economists have been like “Cafeteria Catholics,” embracing the ideas that support neoliberalism while conveniently overlooking the elements that would challenge existing power structures.

In Jennifer Burns’s biography, Milton Friedman: The Last Conservative, the Stanford historian documents the intellectual evolution of the economics discipline as told through the life and work of Friedman. What is immediately striking is that the tenets of economics we consider self-evident today were just taking shape in the 1940s and 1950s when Friedman came up through Rutgers and the University of Chicago. In fact, Friedman struggled to get his dissertation approved, and his doctorate was delayed for years even as his profile and influence in policy circles grew. Evidence that despite its predictive goals, economics seems to be perpetually a step or two behind the domain it exists to describe.

Friedman’s price theory and monetarist ideas were decidedly heterodox when he developed them. Graphical economics, concepts like supply and demand curves, was itself a relatively novel development. Friedman leaned heavily into the intuition of these models for his own theories, believing that free markets and the resulting price signal were the best way to set up thriving economies. This was not such a departure from classical economics, but it was decidedly out-of-vogue following the Great Depression. Where classical economics focused exclusively on the supply side and cost of production, Friedman adapted the models to account for consumer demand and the now bedrock idea of utility maximization.

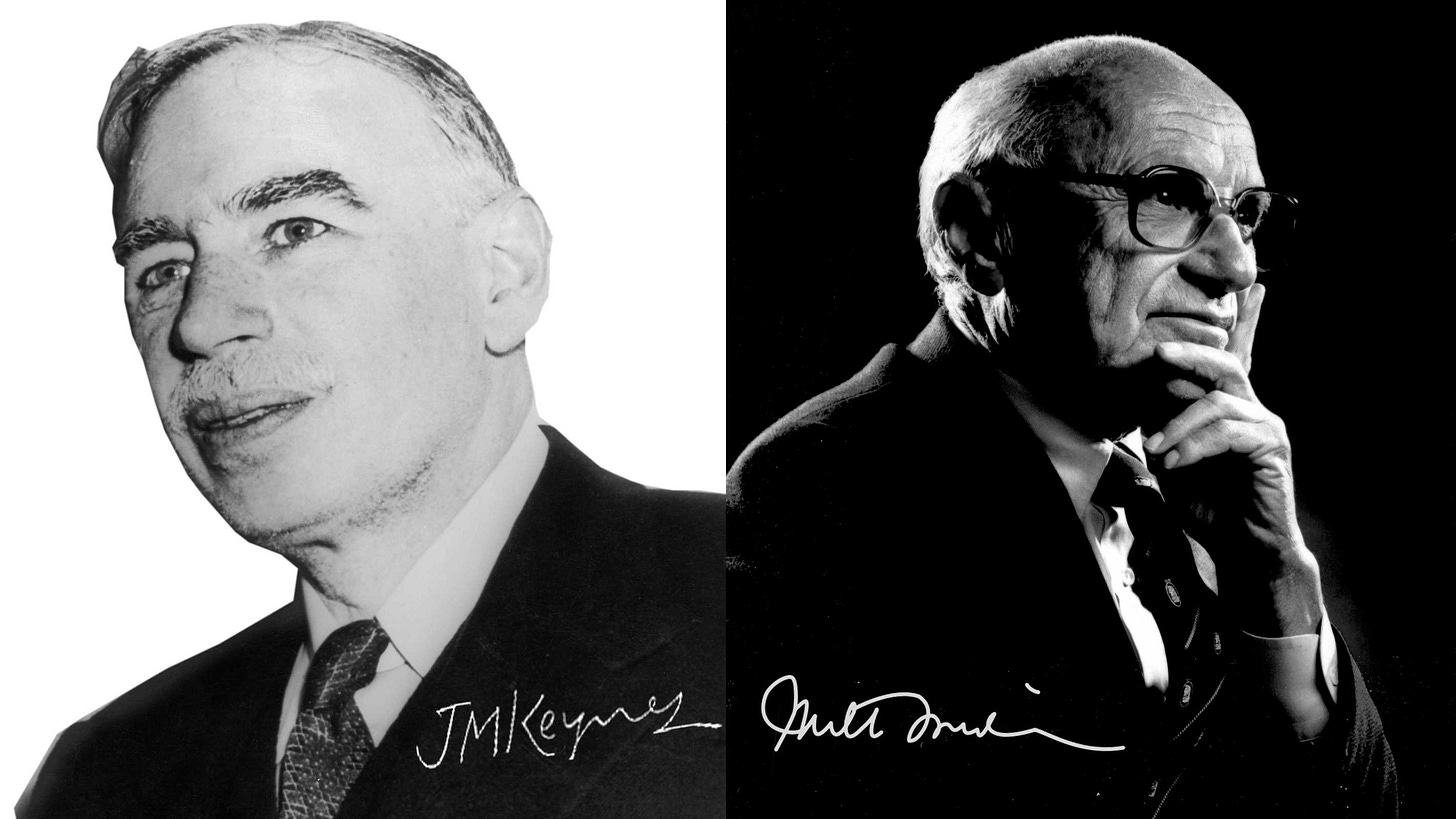

It is hard to overstate the impact the Depression had on economic theory and Friedman’s ideas in particular. The experience gave rise to John Maynard Keynes, whose notions of more managed economies made him a celebrity in New Deal America. These coincidences, Friedman’s post-Depression training and the popularity of Keynes, defined Friedman’s career as a countervailing force to Keynesianism. Notwithstanding, Keynesians won the larger part of the 20th Century. Burns writes,

“This convergence between policy-makers and professors was significant. Keynes’s ideas provided a theoretical rationale for continued New Deal spending. In turn, Keynesianism suggested a route to power for economists. Going far beyond the sort of technical work that Friedman had done, Keynes’s ideas positioned economists as strategic policy experts, even arbiters of the government’s role in society.”

As Burns describes, two trends drove us toward the economics of today: The increasing use of complex mathematical economic models and the fading emphasis of political science in economics. Indeed, before Friedman’s vintage of economists, the field was a study of Political Economy that gradually morphed into a quantitative endeavor that sought to establish a reputation of rigor akin to the natural sciences.

The growing ability to collect and analyze data meant that phenomena considered social or political before could now be understood in terms of equilibrium science. For Keynes, that meant that the impacts of fiscal or monetary intervention could be predicted and thus managed, while for Friedman, it provided evidence that such meddling was merely distortive. While both tried to present their economic theories as apolitical, the Keynesian triumph highlights the primary blind spot of what would become known as “The Chicago School.” Price theory and monetarism assumed a political vacuum in a time of intense realpolitik.

This blind spot directly threatened Friedman’s legacy twice, first in his opposition to the Civil Rights Act and again in supporting Pinochet’s brutal regime in Chile. Both were positions he took in service, or rather faith, that economic freedom was a precondition of political freedom. Despite these missteps, this faith would ultimately become part of the “Washington Consensus” that until very recently defined U.S. foreign and trade policy. Whether during the Cold War or our current economic war with China, the belief that access to global markets would, over time, lead to political freedom and greater alignment with our foes has repeatedly failed.

The arenas in which Friedman’s other ideas have been implemented have similarly spotty track records. Friedman’s version of free markets is not entirely the laissez-faire ideal Libertarians present, but it is generally reflected in our current regime of greater privatization, deregulation, and free trade. Thatcherite Britain is perhaps the purest Petrie dish of these policies. Margaret Thatcher, under the heavy (although not always public) influence of Friedman, took to privatizing state-owned enterprises, weakening labor unions, and lowering taxes.

Again, ignorant of the political realities, these policies came with real long-term social costs, such as rising inequality, unemployment, and the decline of traditional industries. Britain also represents the degree to which these ideas became the global neoliberal consensus. By the time the Labour Party regained the Premiership with the election of Tony Blair in 1997, deregulation, lower taxes, and fiscal austerity remained the prevailing economic schema. Britain has struggled with economic malaise and social unrest throughout.

Domestically, Friedman’s legacy is more monetary. His most enduring political and intellectual contribution is establishing the study of monetary aggregates. Friedman’s edict that “inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon” took on crucial relevance during the inflation shock of the 1970s. Although he is known for letting interest rates rise unabated, Fed Chair Paul Volcker claimed he was more concerned with controlling the money supply. Volker said, with a prescient understanding of the limits of policy transmission,

"The significance of a particular level of interest rates is more difficult to interpret during a period of accelerating inflation."

Friedman advocated for a fixed level of monetary expansion, suggesting something in the low single digits while allowing interest rates to be set by the market. Even as Volker pursued the core of Friedman’s thesis, he would not commit to his mechanistic approach. Thatcher’s experience in Britain showed that once a monetarist policy was declared, it became difficult, possibly existential, to move away from it. The memory of keeping the money supply disastrously constrained following the Great Depression was still fresh in the minds of policymakers, and the idea of rigid, rules-based approaches was unpalatable.

The monetary regime we are left with today reflects the tension between Friedman’s core principles and the evolution of economics into a quantitative field aspiring to scientific precision. The importance of money supply is self-evident, yet our policymakers maintain the hubris that they can tune economic activity through interest rate changes. The modern Fed has become more transparent yet less predictable. As a result, policy is less and less executed by rates or monetary levels and increasingly by carefully crafted releases and intense coverage of “Fed Speak.”

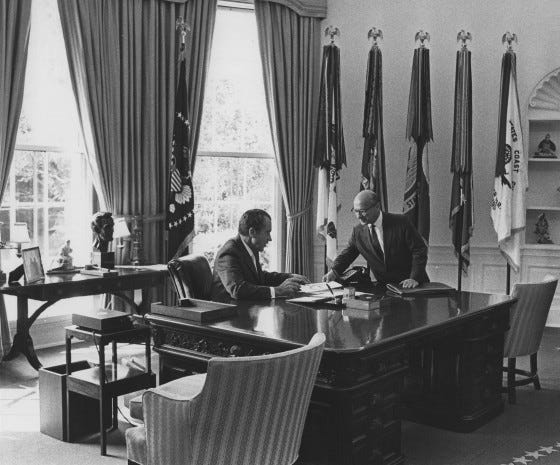

Part and parcel to this modern regime is Friedman’s advocacy for floating foreign exchange rates. As a natural extension of his belief in free markets, Friedman saw no reason why, in the absence of a proper gold standard, exchange rates could be optimally managed under the Bretton-Woods agreement. Increasingly globalized trade meant the dollar’s relative strength significantly impacted the U.S.’s trading prospects. Friedman’s influence on the Nixon administration helped end the global dollar-based accord. Floating currency regimes unlocked the free flow of capital between countries and ushered in the era of Globalization.

When combined with “independently” determined money supply, deregulation, and greater privatization, the modern economic regime took shape. The Reagan-Bush-Clinton-Bush Era saw the ascension of what we now commonly refer to as neoliberalism. While it is not a perfect reflection of Friedman’s ideas, his influence on it is undeniable. We are left with a Keynesian desire to manage the volatility of global economics, executed within a framework of free trade and capitalism. Friedman might argue that the level of intervention in the current system distorts incentives that would direct capital to more productive uses. In essence, neoliberalism is fantastic at generating GDP but fails to create broadly shared wealth gains.

Labor and manufacturing are constantly shuffled between lower-cost geographies, while developed nations focus on supporting financed consumption. Wealth gains accrue to capital owners for whom there are fewer and fewer prospects for productive domestic investment. As Hyman Minsky identified, this managed approach creates an illusion of stability while risks accrue unseen until a dam-breaking moment. Whether caused by brittle supply chains, geopolitical flare-ups, or financial volatility, disruptions seem to always require a little more State and a little less Markets.

To its credit, Burns’s biography is no hagiography. In her epilogue, she references the famed 1979 Donohue appearance where Friedman famously says, “If you want to know where the masses are worse off, worst off, it’s exactly the kinds of societies that depart from...” capitalism and free trade. Burns notes that by 1995, Friedman was beginning to recognize his blind spot. Writing for the Washington Post in 1995, he recognized that liberalized free trade and telecommunications advances “threaten advanced countries with serious social conflict arising from a widening gap between the incomes of the highly skilled (cognitive elite) and the unskilled.”

Friedman, known for being “against government at almost any time,” got essentially half his wish. While the government has grown pretty much unabated since the New Deal, State capacity has been gutted at the hands of Globalization and financialization. The GFC and COVID revealed the growing cracks in the neoliberal order. There was a collective realization that our path of forward progress was not necessarily manifest. The Economist asks rhetorically in its review of Burns’s biography, “Is the age of Milton Friedman over?” The question belies a more profound truth: The adverse effects of our current political economy are not due to mismanagement per se but rather a natural end-state of a system that maximizes shareholder returns with only performative regard for social or political realities.

The post-Friedman era is being defined in real-time, with both U.S. parties making overtures towards populism, protectionism, and broadly defined industrial policy. The economic rise of China presents the first real challenge to the corporatist security state that has reigned since the fall of the Soviet Union. Tariffs, The Inflation Reduction Act, and the CHIPs Act are significant departures from the global consensus of the 1990s and 2000s. Still, they are not yet part of a larger political project or well-defined concept of post-neoliberalism. As is often the case in American politics, they are mostly reactionary. A new consensus will depend on both the Right and Left’s interest in forging a new economic path for the West and, by extension, the free world.

In the 20th Century, economists transcended the halls of academia to become key government advisors and strategic policymakers. Friedman and his contemporaries accomplished this largely by separating politics from political economy. The shape of markets and policy should economics regain its political valence remains an open question. Burns stops short of making predictions in this regard, instead leaving us with a quote from Joe Biden’s 2020 presidential campaign: “Milton Friedman isn’t running the show anymore!”