Something to Stew On

Getting a Dividend from Berkshire the Hard Way

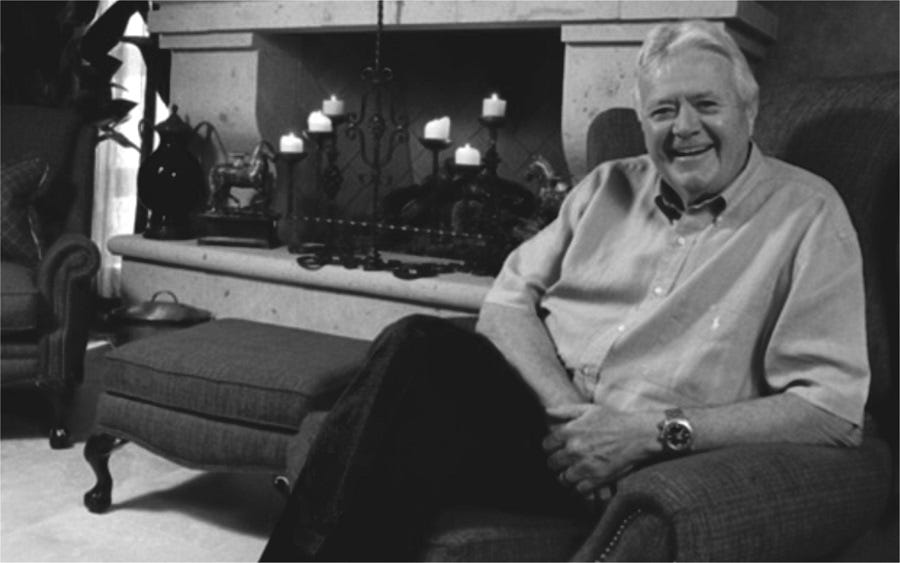

When Stewart Horejsi (pronounced HOR-ish) graduated from the University of Kansas in 1962, he returned to sleepy Salinas to take over his family’s welding supply business. In 1980, frustrated with the encroaching competition on his business, he began buying stock in Berkshire Hathaway. And, as the story often goes, he didn’t stop. In addition to dumping most of the family’s welding supply profits into Berkshire, those initial purchases made Horejsi a billionaire three times over. According to Forbes, he attended Berkshire annual meetings when there “were fewer than a dozen people in folding chairs.” Judging by the roughly 40,000 in attendance at last year’s AGM, the Church of Buffett has grown much faster than the ranks of billionaire shareholders.

For Never-Sellers like Horejsi, large Berkshire fortunes present a problem, albeit an enviable one. As Berkshire pays no dividends, they must part with the shares they have held so dear to reap the rewards of their investing acumen. Horejsi found an elegant, although not entirely straightforward, solution.

In the early 2000s he began acquiring large stakes in closed-end funds (CEFs), taking over as manager via proxy contests to benefit from management fees on the capital. Unlike open-ended mutual funds or exchange-traded funds (ETFs), where investors can come and go with their capital at net asset value, closed-end funds have permanent capital. Horejsi realized he could use a small portion of his wealth to gain control of the Funds, then immediately fill them up with Berkshire again, getting access to leverage and reaping the benefit of the management fees.

A closed-end fund starts life through an IPO process where an investment manager raises a fixed amount of capital from investors. Once public, the shares trade on exchanges like stocks, with prices determined by supply and demand rather than directly tied to the fund's asset value. This creates a dynamic where the fund trades at prices different from its net asset value (NAV) - either at a premium or, more often, at a discount. High fees and unaligned management tend to drive larger discounts in CEFs.

Boaz Weinstein of Saba Capital has made waves this year, taking on large CEF managers to wrest control of the funds. While still profit-driven, Weinstein’s aims are more noble. He looks for CEFs trading at large discounts and then pressures the managers to either repurchase shares or liquidate the fund, earning the spread as price and NAV converge. Conversely, Horejsi needed a vehicle to extract cash flow from his Berkshire holdings. Because CEFs typically charge their management fees on net asset value, not market capitalization, he was not concerned with discounts nor closing them.

In 2002, the $320 million First Financial Fund, distributed by Prudential and managed by Wellington, was the best-performing CEF of the previous decade. Horejsi acquired 40% of the outstanding shares through family trusts and related entities. In June of that year, Horejsi launched his proxy fight, soliciting investors under the name Shareholders for Tomorrow and alluding to the Enron scandal in his appeal to add his board members instead of the incumbents. Keep in mind First Financial Fund had excellent performance. In fact, per the WSJ, Horejsi himself had written the fund’s chairman just a month before he began his proxy fight, saying, “Thanks for a job well done and keep up the good work."

The letters criticize the two incumbents for sitting on the boards of at least 74 other funds sponsored by Prudential, saying that "it is impossible" for them to give sufficient attention to any one fund or to "protect the Fund from something going awry." - WSJ

Horejsi claimed he was not trying to take over fund management but simply add new board members who could be more focused on the fund. First Financial’s board knew better, as Horejsi had already successfully taken over the management of two other CEFs, the Boulder Total Return Fund and the Boulder Growth & Income Fund. Not only did Horejsi appoint himself as manager of those funds, he also raised the advisory fees and hired a firm he owned to be the fund administrator. Once in control of those funds, he initiated a transferable rights offering to grow the Fund’s assets at the expense of diluting existing shareholders.

First Financial’s bylaws required 50% of all outstanding shares to vote for Horejsi's proposed changes. Ultimately, First Financial won the proxy fight despite Horejsi winning the plurality of votes. While the existing board won just 33% of the vote, Horejsi fell short at 47%. He briefly blustered he would challenge the 50% rule in the Courts despite installing the same provisions in the Boulder funds just seven months earlier. Horejsi gave up the fight on First Financial and focused his time on the Boulder vehicles, which he loaded up with stock in none other than Berkshire Hathaway.

In 2022, after 20 years at the helm of Boulder Growth & Income, Horejsi retired. He handed off fund management to Kansas-based Rocky Mountain Advisors and its principals, Joel Looney and Jacob Hemmer. Upon retirement, the fund changed its name to the SRH Total Return Fund with the ticker STEW 0.00%↑ .

In Horejsi’s tenure, the fund traded at an average discount of 14.5%; today, that discount is more than 20%. Backing out the nearly 50% owned by Horejsi-related entities, Stewart Horejsi extracted about $100 million in fees over the prior two decades. The family’s proportionate share of dividends from the fund added another $50 million. Thanks in part to the discount, the fund now yields 3.9%. As of the latest filing, 44% of the fund’s assets are in Berkshire Hathaway.

New management has taken a light touch in Horejsi’s absence. They have kept turnover below 10%, making only minor tweaks at the bottom of the portfolio. Last quarter, they added positions in Forward Air Corp ( FWRD 0.00%↑ ), First Watch Restaurant Group Inc ( FWRG 0.00%↑ ), and Inter Parfums, Inc. ( IPAR 0.00%↑ ) that, in sum, amounted to less than 3% of assets. All in a day’s work for a 90 basis point management fee.

To its credit, the fund uses modest leverage and secured sub-3% borrowing costs through 2030. Of course, leverage also helps it grow the asset value on which it charges fees. A share repurchase plan has been in place since 2017; so far, they have retired around 10% of the shares outstanding, presumably attempting to close the now yawning discount.

For investors who couldn’t resist the siren song of “Berkshire at a discount,” the results have not been nearly as remunerative as those lucky enough to be related to Horejsi. Over the previous decade, the fund has lagged Berkshire and the broad index by 600 basis points annually.

There are rarely dollars selling for eighty cents in markets, and waiting for NAV discounts to close is the path to a long, miserably investing career. Stewart Horejsi, despite his pious Berkshire AGM attendance is in many ways a foil to Buffett. There is no small irony that a man whose wealth benefitted directly from Buffett’s regard for shareholders, failed to internalize those lessons for his own.

People will really dream up anything if you give them enough time!