A major transaction within the leading commercial real estate brokerages is imminent. Cushman & Wakefield, with its catch-22 of having to cut expenses into an expansion, is an ideal target for a strategic acquirer.

Procyclical businesses like investment banking or real estate brokerage are prone to lean periods. That notwithstanding the pandemic impact on leasing (especially office), the rapid credit expansion of 2021 and 2022, followed by the Federal Reserve’s aggressive hiking cycle constituted three back-to-back “100-year floods” for the commercial real estate brokerage business.

According to JLL Global Research by the end of the second quarter of 2023, Global Commercial Real Estate Investment volume was down 53% year-over-year, by the third quarter the decline had only improved to -48% year-over-year. The fall-off in volumes was exacerbated by an ~85 basis point rise in cap rates across asset classes. The $25 billion brokerage behemoth CBRE ( CBRE 0.00%↑ ) saw earnings per share nearly cut in half. If brokers are fond of referring to the Eat What You Kill ethos of the industry, then the feast of 2021 and 2022 had turned decidedly to famine.

This crucible has left the strongest firms bruised but still dominant, while weaker firms face an existential recovery. A major transaction within the leading brokerages is imminent. Cushman & Wakefield ( CWK 0.00%↑), with its catch-22 of having to cut expenses into an expansion, is an ideal target for a strategic acquirer.

A Distant Third…or Fourth

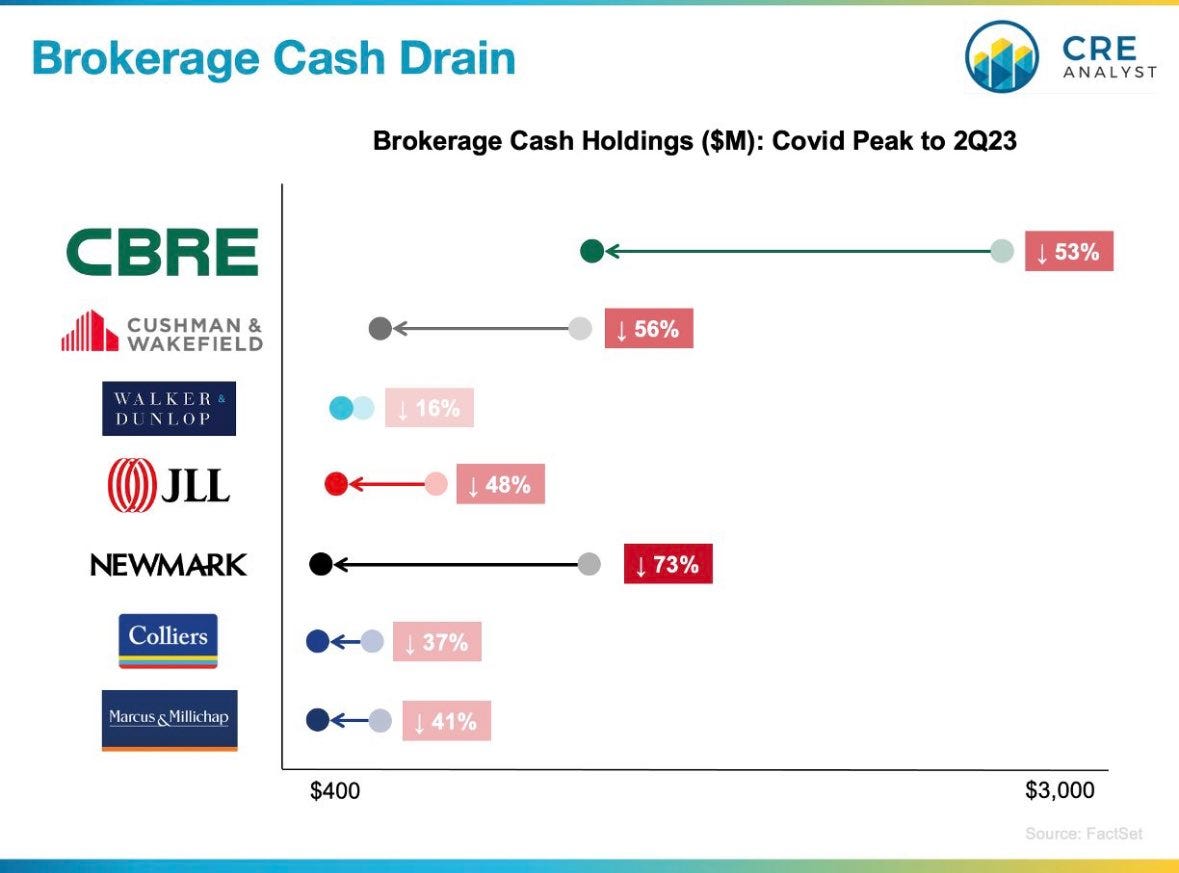

Brokerages burned cash to ride out the transaction slowdown. From their respective third quarter 2021 peaks, Cushman & Wakefield reduced cash-on-hand by $600 million, while CBRE saw its cash buffer decrease by over $1.5 billion. The key difference being that CBRE’s cash burn was 5% of its market capitalization, while Cushman’s was closer to 30%.

The brokerage business is ultimately a talent business where growth is powered through acquisitions. Since TPG portfolio company DPZ bought Cushman & Wakefield in 2015 for $2 billion, the combined firm has spent over $600 million on acquisitions financed primarily with debt. Brett White, the would-be Cushman CEO (now Executive Chairman) at the time said the transaction would create a “third formidable competitor at the highest end of this industry.”

That dream has largely not come to fruition. Cushman’s investments have not consistently generated positive returns on invested capital and the top-line has grown at an anemic 5.58% since 2015 compared to 10.25% for CBRE and 19.85% for JLL ( JLL 0.00%↑ ). Canada-based Colliers International ( CIGI 0.00%↑ ) has grown revenues 14.72% over that period, quadrupling its market capitalization along the way.

Catch-22

Cushman’s debt-fueled growth, and its failure to produce results, now poses a capital allocation challenge. Of the company’s $667 million estimated 2024 EBITDA, nearly $250 million will go to debt service. The business must invest to grow, but its ability to do so is considerably constrained by the current state of the balance sheet. Cushman is looking to find $160 million of on-going cost savings to help bring it’s leverage profile more in-line with its competitors. Michelle MacKay, who took over at CEO as Cushman’s CEO in July, tried to thread the needle of these competing goals on the third quarter conference call:

So we want to both be reducing debt and investing in growth, right? This is not an either/or conversation. And I think what's important for everybody to understand is that we're committed to reducing our debt level over time as we grow the business because we believe this is the optimum path to generating strong shareholder returns.

I believe it is, in fact, an “either/or” proposition especially in the context of the changing brokerage landscape. All brokerage firms have sought to remake themselves in the image of other professional services firms, with more recurring revenue and less dependence on transaction work. This has expressed itself in the form of corporations outsourcing their internal real estate operations to the large brokerage firms. These are competitive contracts that must be won with the accompanying fixed costs and thinner margins of servicing enterprise clients.

In 2023, over half of Cushman’s revenue will come from services, or non-transaction related fees. Still, nearly 30% of revenue comes from leasing and another 13% from brokerage. Transactions and leasing are higher margin businesses key for generating cash flow that can be reinvested into growing the more stable services business. In November, Brookfield fired Cushman from handling its US office and logistics business, possibly in retaliation for not taking more space in a Brookfield-owned building in Manhattan. Cushman’s response reflected their new cost discipline:

While completely surprised by this reaction, we consider disciplined management in the best interest of our firm, employees and shareholders.

The other stakeholder group that typically bristles at cost-cutting is the brokers themselves whom, with fewer marketing and back-office resources, begin looking for lusher pastures in which to “eat what they kill.” Easing capital markets conditions and rebounding transaction volumes can take the pressure off Cushman, but absent a transformative transaction, the firm cannot compete with its better-heeled competitors. Something has to give. Cushman can sell business units, issue shares, or put itself on the block, but it cannot fundamentally shrink and grow at the same time.