Even if you are unfamiliar with Starwood’s sprawling real estate empire, you are likely familiar with its Chairman, Barry Sternlicht. A too-tanned Sternlicht has been a fixture in financial media, calling for the Fed to cut rates practically since they began raising them. This is self-serving to a large commercial real estate owner like Sternlicht. His 32-year-old firm has around $115 billion of assets under management; by some measures, it is the largest owner of apartments in the U.S.

Nested within this real estate giant is Starwood Property Trust STWD 0.00%↑ -- a publicly traded mortgage REIT with a market capitalization of $6.7 billion. It is important to distinguish between your “plain vanilla” mortgage REIT and STWD. Most Mortgage REITs (MREITS) are relatively straightforward pools of real estate loans leveraged with various forms of debt. The Mortgage REIT moniker can be an albatross for listed entities.

First, Mortgage REITs are “out of mandate” for many managers, especially passive strategies. The S&P 500 contains zero mortgage REITs. That lack of “natural” buyers means that MREIT flows are relegated to sector-specific vehicles or bold active managers. Secondly, the relative opaqueness of MREITs and the interest margin nature of the core business model means that there is little if any, reason for an MREIT to trade a premium to book value. Finally, their stubbornness to exhibit multiple expansion and the high portion of returns that come from dividends make them less attractive to “fast money” pools of capital.

The level of sophistication for MREITs runs the gamut from “six guys with a Bloomberg” to massively complex firms with diverse business lines. Starwood is the latter. In some ways, it more closely resembles an alternative asset management firm than an MREIT. Its four business lines include commercial and residential lending, infrastructure (energy) lending, special servicing via its captive ownership of LNR, and a property portfolio of affordable housing and medical office buildings. On balance, traditional CRE lending accounts for 65% of distributable earnings, but the other 35% is exposed to unique economic factors beyond simply CRE credit spreads.

I don’t wish to regurgitate the 10-K here; Starwood believes it has unique competitive advantages in each of these spaces and, further, that these units, or in their parlance “cylinders,” ultimately complement one another. It is not a stretch to see how the REIS segment, which originates, invests, and services CMBS, might be valuable to a senior originator. The property portfolio of Medical Office and Affordable housing is itself unusually housed within a mortgage REIT. Infrastructure lending is also an outlier category that obscures the traditional MREIT metrics. This is all to say that coming up with a valuation is a challenging prospect, one for which STWD’s investor relations give little guidance.

Price to Book Value

With such a complex and varied operation, the potential pencil-sharpening that could be done on both sides of the balance sheet is nearly endless. The sell side, IR and most investors look to a simple price-to-book method to arrive at some value assessment for MREITs. Using that basic heuristic, STWD’s shares are experiencing the effects of CRE’s dour outlook.

That said, US office assets represent just 11% of the total asset base; across commercial lending, the book is around 60% LTV. CEO Jeffery DiModica said on the first quarter call,

“Our largest property type multifamily, which is 21% of our company's assets, has an average remaining term of 2.7 years and continues to experience year-over-year rent growth with same-store rents up 3.4%.”

Interestingly, STWD did no new loan originations in Q1 but issued $600 million in senior unsecured notes at 7.25% -- while this issuance raised the cost of debt, it brought the company’s total availability capital for lending to $1.4 billion more than double the $635 million available at the end of Q1 2023.

There is an argument that newly originated real estate debt is among the best risk-adjusted returns available in the CRE space today. STWD stands to be a liquidity provider as refinances, and new acquisitions occur at attractive valuations ahead of a potentially falling rate environment.

The analyst looking to price-to-book for valuation needs to assess the likely path of originations and then the market’s propensity to put at least a 1x multiple on net assets. This approach works well enough, but in practice, it becomes a Keynesian Beauty Contest, with the multiple reflecting the market’s view of the portfolio’s credit and the issuer itself.

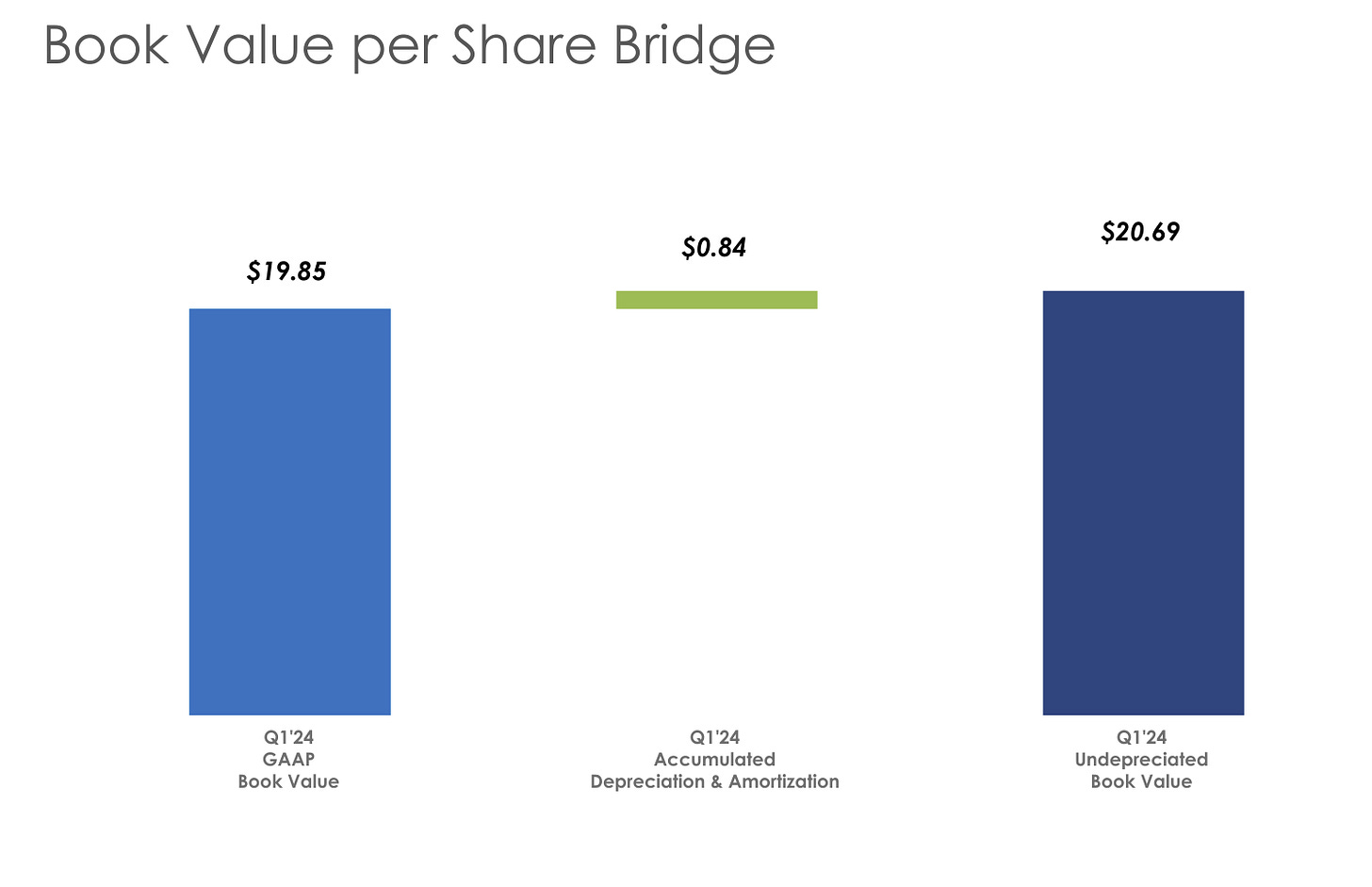

At the end of Q1, the share price represented 0.96x of undepreciated book value. Undepreciating book value helps a bit, but this also includes roughly $1.70 per share of “Current Expected Credit Losses” CECL, which I will address shortly.

The “Excess Spread” approach

In structured or asset-backed finance, the excess spread simply represents the difference in yield between the underlying pool of assets generate and the yield the security pays. Typically, this is the excess cash flow available to the instrument's equity tranche. There is no way to truly simplify the model for Starwood; the organization and capitalization are simply too complex. There is frustratingly little middle ground between slapping a price-to-book ratio on it and building a full three-statement model. The idea of excess spread, however, does provide a useful framework.

Again, as an STWD equity holder, you are mostly in the game for the dividend, its potential growth, and the thin hope of multiple expansion. I believe the aforementioned complexity takes trading a sustainable premium to book value off the table. With that, the analyst should be most concerned with the spread the dividend offers to other yield opportunities and, crucially, how well it is covered by the business's core investing functions.

To that end, I look at each business unit, its disclosed yield, and the overall leverage the company employs: