As fig leaves were replaced by loin cloths, so too later were suits of armor succeeded by suits by Zegna. Was this a societal advancement, perhaps.

- Harley Bassman “The Convexity Maven”

There is an inclination among financial writers to center the narrative arc of mortgage securitization around the Great Financial Crisis. The speculative fervor and subsequent fallout make for a compelling denouement, but the story of credit in the housing market straddles a longer history. Since the expansion of consumer mortgage financing in the 1970s, residential housing’s importance to not only the financial system but also to the US’s economic health has grown considerably. It has changed the nature of home ownership and the social makeup of our communities. We have evolved Thomas Jefferson’s vision of yeoman farmers1 in ways unimaginable to the Founders or even to early 20th-century Americans. In the process, the relatively straightforward process of financing a home has become central to the plumbing of the global financial system.

The 30-year mortgage is an aberration internationally, but few Americans fully appreciate its oddity, a benefit bestowed by US Dollar hegemony. US homebuyers can, with relatively modest means, secure long-term fixed-rate debt for sums many multiples their annual wage. They can also enter derivative bets tied to their mortgage like “buying points,” restructure via cash-in refinances or add layers to the capital stack via HELOCs. In the increasingly financialized landscape of America’s economy, the home mortgage remains the ultimate consumer and financial “product.”

Despite its importance to the general wealth of the nation, the exact machinations of a mortgage are a mystery to most homeowners and many professional investors alike. A simplified enough understanding is that home mortgages are pooled and securitized for investors, and until the creation of the Ginnie Mae in 1968 (and later Fannie and Freddie) this would have been mostly accurate. The creation of the Government Sponsored Entities (GSEs) created a key layer to the mortgage market that transformed MBS into something foundational to the schema of financial markets.

A Feeble Attempt at Synthesizing MBS Dynamics…

“Sure, cried the tenant men, but it’s our land…We were born on it, and we got killed on it, died on it. Even if it’s no good, it’s still ours….That’s what makes ownership, not a paper with numbers on it."

"We’re sorry. It’s not us. It’s the monster. The bank isn’t like a man."

"Yes, but the bank is only made of men."

"No, you’re wrong there—quite wrong there. The bank is something else than men. It happens that every man in a bank hates what the bank does, and yet the bank does it. The bank is something more than men, I tell you. It’s the monster. Men made it, but they can’t control it.”

―

The Grapes of Wrath

John Steinbeck

The mortgages of Steinbeck’s tenant men exemplify the primary issues with pre-GSE mortgages from a banking perspective. For banks, mortgage lending is a fraught, capital-intensive endeavor if loans must be held on their books. Harley Bassman, “Convexity Maven” and Managing Partner of Simplify Asset Management:

There are three huge problems with this sort of finance; the first (ignoring fractional leverage) is that the bank is limited to lending only its total deposits. The second is the risk they must pay depositors more than the fixed-interest they charge for the mortgage loan. And the third is the liquidity risk of a “bank run” if the depositors want their money back before the loan is paid off.2

The GSEs perform a sort of financial alchemy. Beyond simply securitizing a pool of mortgages, they wrap them in the luminescence of a government guarantee. The “if-needed” full faith and credit of the US Government. This process often uses the vernacular of the originator “selling” the loan to the GSE, but that’s not quite accurate. Rather, the GSE takes a fee for bundling mortgages into guaranteed MBS and handing it back to the originator to sell to dealers and then on to pension and mutual funds. The yield drops down at each of these transactions as each participant makes a small profit passing the security down the line. This transformation moves Mortgage Backed Securities (MBS) from something in the orbit of financial markets to the Center of the Universe. Bassman again,

…the Bond market is just much larger and more liquid than the Equity market. I remember when some wingo from the Carolinas could ask for an offer on $12bn FN 5% bonds with barely a blip in price; in contrast, a 1 million share inquiry on most single-name stocks would roil the market. At the top of the heap are Mortgage bonds, which finance the residential housing market - our largest wealth category which drives 15% of the US economy.

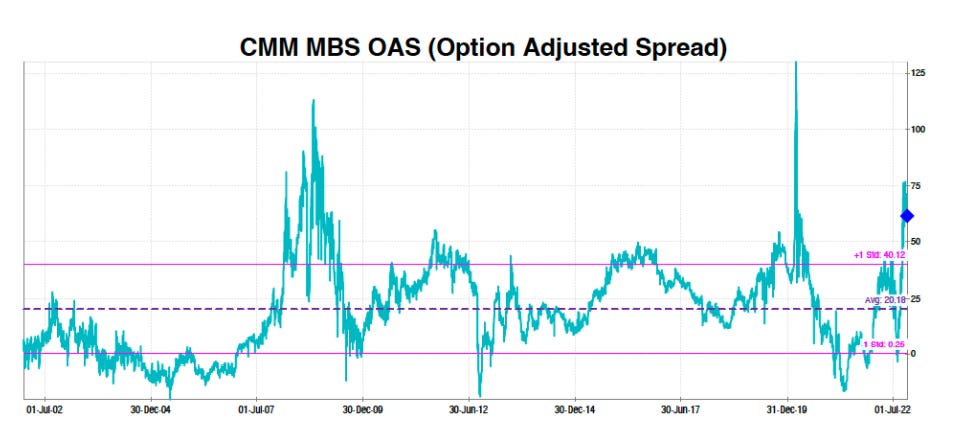

Fixed-income securities are collections of different types of risk: Credit, Interest Rate, Duration, Liquidity, and Volatility. The government guarantee MBS receives removes credit risk. The payments and principal are no longer at risk of the borrower welching on the loan. The remaining risks are just as material, but to an extent, more quantifiably understandable than the credit risk of individual or even pools of residential borrowers. With liquidity and credit risk effectively removed from MBS securities, what remains is a unique product in the eyes of financial markets. Guillermo Roditi Dominguez of New River Investments on Odd Lots:

I think one way to look at it is a mortgage-backed security is essentially similar to a covered call in equity terms. And that means that you have all of the downside and you know, very, very little of the upside and you trade that in for a little bit of extra coupon. And when rates were going down, everybody was upset about it because Treasury bonds were going up in price. People were making money there. If you held MBS, you got your money back and then when you went to buy new bonds, you bought them at a lower yield. And right now what we’re seeing is all of a sudden bond prices are going down, yields are going up and you’re not getting any cash flows so you don’t get to reinvest that money.

Borrowers have the penalty-free option to refinance their mortgage and tend to exercise it when rates are falling. This duration risk accounts for the higher yield MBS earns over similarly guaranteed government debt. Of course, borrowers repay their mortgage for any number of reasons and life events. Moving for a better job, death, divorce, or having a child may all impact a borrower’s propensity to repay a mortgage. Wall Street has employed armies of Ph.D.s to try to divine these prepayment rates.

The most intimate parts of many Americans’ lives are actuarially assessed and priced into assets that are then sold back to them in mutual funds, insurance policies, and savings accounts. A full circle of nominal “wealth creation” via the repackaging of risks both endogenous and exogenous.

Spread businesses like banks and insurance companies love MBS for its hyper liquidity, government backing, and higher yields until they hate it for the volatility of the option value which accrues to the borrower.

Duration extends as borrowers choose not to exercise their options, making the holders of MBS more exposed to interest rate changes. If the value of a mortgage security can be thought of as a US Treasury minus the value of the option, then the value of the security goes down as the value of the option goes up.

Borrowers and banks alike benefit from the increased throughput the GSE alchemy provides, while Wall Street builds and markets a variety of products for investors to gain or hedge exposure to the asset class. MBS is core to bank balance sheets3, money market funds, and the liability matching that pensions and insurance companies undertake.

It should be noted that even this treatment is barely wading into the shallow end of the complexity that surrounds and supports the MBS marketplace.

Financialization and its Discontents

You’ll notice that to this point I have not spoken much about the housing market itself. The market for MBS and the housing market are simultaneously joined at the hip and disambiguated from one another. That is the inherent conceit of financialization. The government guarantee on mortgages creates demand for mortgage securities independent of the demand for housing. When the demand for debt outruns productive uses for that debt you get…issues. A useful analogy here is Student Debt, where government sponsorship created a demand for paper that was not necessarily related to the demand for a college education. A variety of actors stepped up, both for-profit scams and traditional institutions, to prime the pump for the flow of that paper. MBS creates new layers of transactions, fees, and financial products to both gain and hedge exposure. Many facets of our economy serve the creation and trading of MBS securities. Those actors are both levered to and agnostic towards the actual underlying housing market. Again, look no further than the GFC for what happens when this form of economic “growth” is taken to its only logical conclusion.

Collapse, while visceral, is not the only impact of greater financialization. Steinbeck’s tenant men experienced the capriciousness of banking in the form of foreclosure, our financialized version experiences it in more subtle ways. Hoisington Asset Management, Q3 2021 economic outlook took on the less acute symptoms of financialization.

Excessive indebtedness acts as a tax on future growth and it is also consistent with Hyman Minsky’s concept of “Ponzi finance,” which is that the size and type of debt being added cannot generate a cash flow to repay principal and interest. While the debt has not resulted in the sustained instability in financial markets envisioned by Minsky, the slow reduction in economic growth and the standard of living is more insidious.

The chart above shows the marginal dollar of GDP generated from the marginal dollar of debt. The impact of greater debt at some point stops finding its way into the real economy and instead gets trapped circulating within financial markets. It inflates asset values without generating broadly distributed wealth. It recruits enterprising citizens into the roles of financiers who can feed the machine of securitization.

Yeoman Farmers to Small-Time Fiefs in Three Generations

American Bonds: How Credit Markets Shaped a Nation by Sarah Quinn, a sociologist, tracks the influence credit has had on America’s social development. The Jeffersonian notion of the yeoman farmer has been reimagined and recast throughout the history of the nation. Jefferson believed ownership was a necessary condition for freedom.

“Dependence begets subservience and venality, suffocates the germ of virtue and prepares fit tools for the designs of ambition,” Thomas Jefferson wrote. In the longstanding American republican ideal, with its roots in the Jeffersonian tradition, working for someone else made a man reliant on another person for his well-being. This dependency was thought to compromise freedom of action and thought, and even the autonomy of a man’s actual vote. In contrast, a man who owned property—as a farmer, craftsman, or small businessman—governed himself. This freed him to contemplate and follow his ideals.

As the US economy developed from primarily an agrarian one to one defined by manufacturing and services, the Jeffersonian ideal needed a vehicle through which to express itself and the family home became both a totem of America’s progress and an aspirational goal.

The ideal of self-governance at work could be reconstituted as that of self-governance at home. After all, could not all the gains associated with independent work also be realized through a kind of domestic dominion? Purchasing a home required frugality, hard work, and reliability. Owning a home, like owning a business, instilled in men a neighborly obligation and sense of pride. All of this created better citizens: “A man who has earned, saved, and paid for a home will be a better man, a better artisan or clerk, a better husband and father, and a better citizen of the republic.” Civic virtue was thus grafted onto the act of owning a home, with the promise of rescuing masculine independence. The detached home itself stood as a physical representation of this independence, the manicured lawn signaling an appreciation for and mastery over nature.

Quinn argues that agency MBS and government influence on credit markets is politically and fiscally “light.” In other words, they create inducements and incentives but do so within the language of free markets and self-sufficiency.

The open obligation of the credit form—the fact that there is repayment—helps people overlook the various opportunities and subsidies also transferred through this process. Subsidies and state assistance then appear to be forms of self-help.

Post-2000 tech began its rapid acceleration, globalization hollowed out much of traditional American employment and stagnant wages resigned large swaths population to the Precariat—“predictability without security.” While the economy evolved around and away from the Neo-yeoman vision of self-sufficiency, the incentives to be a borrower remained. As the economy became less dynamic overall, passive income from rents, financed via subsidized mortgages became not just a viable, but an aspirational path out of professional and financial stagnation.

Such began the rise of the rentier4, not as a pejorative recipient of a government subsidy, but as a bootstrapped entrepreneur. America escaped the feudal empire of the Crown only to rebuild it over several hundred years in the image of Jefferson, under the auspises of free markets, and with the political dressing of social mobility.

Mobility and Social Capital

In 1995 Robert Putnam published “Bowling Alone: America's Declining Social Capital” in the Journal of Democracy. Putnam argues that after experiencing a high point in the 1960s America’s civil and social engagement began to decline. Alexis de Tocqueville recognized that Americans’ propensity for associating with one another was a key ingredient in a well-functioning democracy, “Nothing, in my view,” he wrote “deserves more attention than the intellectual and moral associations in America." Putnam explains the obvious benefits of civic engagement and social capital:

For a variety of reasons, life is easier in a community blessed with a substantial stock of social capital. In the first place, networks of civic engagement foster sturdy norms of generalized reciprocity and encourage the emergence of social trust. Such networks facilitate coordination and communication, amplify reputations, and thus allow dilemmas of collective action to be resolved. When economic and political negotiation is embedded in dense networks of social interaction, incentives for opportunism are reduced.

Putnam points to steady declines in voter turnout and decreases in Rotary membership and church attendance as evidence of fraying social fabrics and declining social capital stocks. Questions about Americans’ daily life as intimate as "How often do you spend a social evening with a neighbor?" have deteriorated steadily in social surveys since 1974.

The connection between a highly financialized housing market and our seeming deterioration of social capital may be tenuous but it is nonetheless pursuasive. The founding of Ginnie Mae in 1968 and subsequently Fannie and Freddie in the 70s and 80s corresponds with these trends, but I cannot say with any authority other than general observation, the role they have played in our de-socialization.

Today, apartment buildings are marketed as “communities” but their desirability is enhanced almost exclusively by various finishes and amenities. Our sense of place is oriented around consumption; we are consumers of our towns and homes but neither members nor stewards of them. Housing units, urban cores, and suburban power centers alike are optimized to be virtually indistinguishable, broadly appealing, and differentiated principally by tax policy and employment opportunities. Cities prostitute themselves to win corporate headquarters. Our pursuit of near frictionless mobility, however, has not resulted in a sustained escape from precarity for most Americans. The resulting decline in social capital has reduced our overall standard of living even in the face of nominal growth.

Putnam himself identified in the mid-90s the impact un-rootedness played in the deterioration of our civic associations5:

Numerous studies of organizational involvement have shown that residential stability and such related phenomena as homeownership are clearly associated with greater civic engagement. Mobility, like frequent re-potting of plants, tends to disrupt root systems, and it takes time for an uprooted individual to put down new roots.

A fair critique of conservatism is that it is a form of misplaced nostalgia. That some time in the past was better than today and simply restoring those conditions would restore our society to that state. I don’t believe the financial system of Steinbeck’s era would create better or more equitable outcomes. GSEs were created to democratize home ownership, but they ended up creating an asset divorced from the economics of that outcome, and today the outcome fails to even deliver the original objective.

In 2012, author Wendell Berry was invited to deliver, aptly, The Jefferson Lecture—our nation’s highest honor for distinguished intellectual achievement. Berry’s speech, titled It All Turns on Affection addressed the issues he had dedicated his life to exploring: Our American obsession with progress and the perpetual dissatisfaction that pushes us forwards but not always upwards:

In such modest joy in a modest holding is the promise of a stable, democratic society, a promise not to be found in "mobility": our forlorn modern progress toward something indefinitely, and often unrealizably, better. A principled dissatisfaction with whatever one has promises nothing or worse.

Thomas Jefferson’s ideal citizen was the independent yeoman farmer, capable of providing for his own family and ensuring his sons’ independence at maturity. The family was central in Jefferson’s vision and was a little republic in its own right, created by a free act of consent between sovereign and equal individual

I began writing this before the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank, and while many details are still unknown the bank held MBS on its books as Held-to-Maturity Securities (HTM). This means the market gains and losses were shielded from view on financial statements. MBS are negatively convex, rising rates hurts their price more than falling rates benefits them. This is why a bank that appears to have $.X assets may really only have $.Y should it need to sell HTM securities, especially in a rapidly rising rate environment.

I want to be clear that this is not a judgment of landlords or those who have built businesses around property ownership. I’m simply suggesting that subsidized debt in conjunction with a less dynamic economy has pushed a greater portion of the population into that line of work than would otherwise be the case.

When Putnam wrote in 1995, home ownership had increased since the 1960s when civic engagement was at its peak. Those trends have slowed or at least been volatile since the original article.

This might be the best thing I've ever read

"America escaped the feudal empire of the Crown only to rebuild it over several hundred years in the image of Jefferson, under the auspicious of free markets, and with the political dressing of social mobility."

This piece hits hard.