The Sand Pile

Michael Mauboussin's "Shift Happens" an exploration of Complex Adaptive Systems applied to Capital Markets

The natural reaction, then, is to modify the current theory as best as possible in order to accommodate reality. However, defenders of the faith can only put so many proverbial fingers in the dam. Eventually, the water gushes forth and the challenging theory gains widespread acceptance.

A common experience in the information age is believing you have a novel theory about something, then finding that not only has someone thought of it but that they've built a reputation and career out of exploring it. If you spend a lot of time thinking about investing, that person is Michael Mauboussin more often than not.

Mauboussin has cut an enviable career path straddling the worlds of practice and theory. He is thorough and thoughtful without being didactic and his time as a practitioner affords him the credibility to talk about the actual work of investing.

In the nineties, legendary investor Bill Miller introduced Mauboussin to the Sante Fe Institute, a multidisciplinary think tank founded in 1984 to conduct research beyond the traditional boundaries of academic disciplines. This multi-disciplinary approach has come to define Mauboussin’s work and makes his writings and research incredibly rich for the intellectually curious.

A few months ago an old picture of the reading list for Mauboussin’s Columbia Business School class surfaced on Twitter. As I worked my way through them, I got caught up in 1997’s Shift Happens which Mauboussin wrote while at Credit Suisse First Boston.

Shift Happens directly addresses what anyone who has moved from academic training to the practice of investing has experienced: The models we are taught explain markets, fall woefully short of explaining markets. Efficient Market Hypothesis or the Capital Asset Pricing Model relies on mimicry of other equilibrium sciences that only economics refuses to let go of.

The bulk of economics is based on equilibrium systems: for example, a balance between supply and demand, risk and reward, price and quantity. Articulated by Alfred Marshall in the 1890s, this view stems from the idea that economics is a science akin to Newtonian physics, with an identifiable link between cause and effect and implied predictability. When the equilibrium system is hit by an exogenous shock, it absorbs the shock and returns to an equilibrium state…The irony is that the convenient, predictable science that economists hold as an ideal— nineteenth century physics— has been undermined by advances such as quantum theory, where indeterminacy is intrinsic. The equilibrium science that economists have mimicked has evolved; economics, by and large, has not.

The implications that the prevailing model may not work are, of course, viewed as an existential risk to the academics who have staked their careers to them. For example, should the assumption of a normal distribution of returns, foundational to classic capital markets theory, be abandoned, it would “invalidate the use of traditional probability calculus.” Yikes.

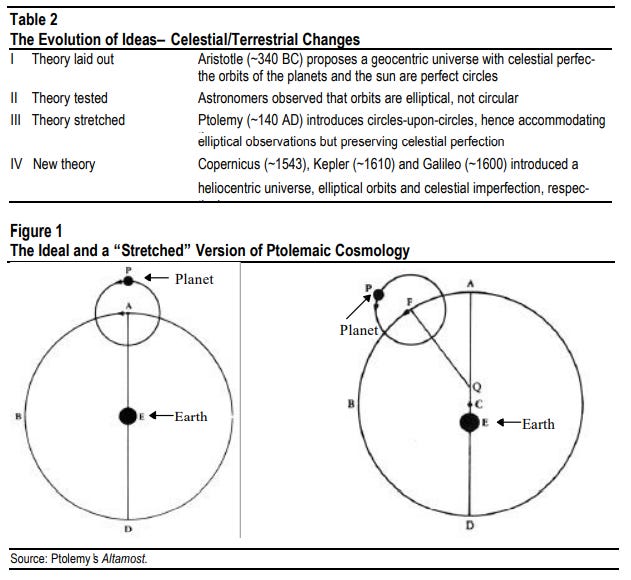

Of course, theories do eventually update and Mauboussin lays out a simple framework by which this occurs using the transition from pre-Copernican astronomy to illustrate.

A theory is laid out in order to explain a phenomenon

Scientists test the theory and find facts that counter it

The original theory is “stretched” to accommodate new findings

A new theory supersedes the old theory

Correspondence

Inherent in the development of models is the use of simplifying assumptions to make useful approximations of reality. As a result, old theories are not really abandoned when a new theory arises but serve as referential checkpoints on our way to a more useful theoretical framework. Mauboussin highlights this nuance through the idea of “correspondence”

Correspondence has two parts. First, a new idea must explain why the old theory worked, while furthering the understanding of the phenomenon being studied. Second, the new theory should add some predictive value.