Hidden Forces

A Factor Investing Renaissance and the Asset Heavy Passthrough Problem

Markets are efficient, but there are different dimensions of risk and those lead to different dimensions of expected returns. That's what people should be concerned with in their investment decisions and not with whether they can pick stocks, pick winners and losers among the various managers delivering basically the same product."

- Eugene Fama

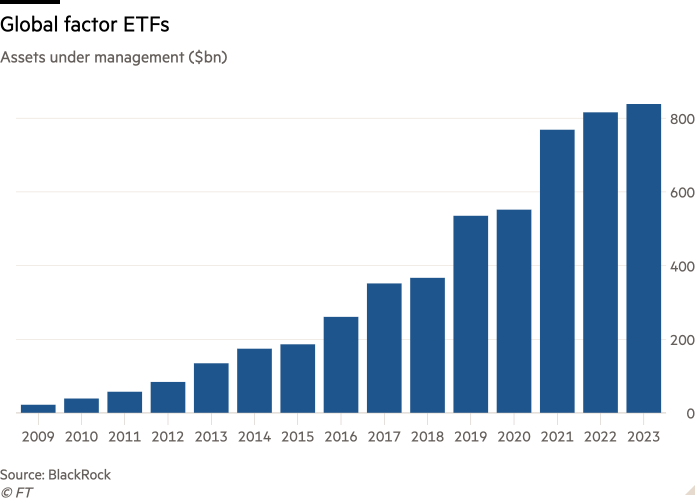

The undeniable allure of quantitative investing has existed since the birth of financial markets. Robin Wigglesworth at FT Alphaville is out recently with a fantastic overview of the quant landscape. As Wigglesworth notes, the idea that the chaotic herd was mere noise amidst a more natural process of asset pricing has created what Sephardi merchant Joseph de la Vega called "a quintessence of academic learning and a paragon of fraudulence," since at least the 17th century.

Factor Zoo

The discovery and performance of various factors is an academic minefield. What at first look like promising results repeatedly fail in the face of either more robust testing or through disappointing live deployment. The challenge lies in finding factors that perform in out-of-sample tests, that are not sufficiently captured by the major factor models, and which are achievable taking into account transactions costs and execution.

Levi and Welch (2014) took the kitchen-sink approach and examined 600 factors from both the academic and practitioner literature. They found that 49% of the factors produced zero to negative premia out-of-sample, suggesting that investing based on the identified factors is only ever so slightly better than tossing coins.

The recent performance of the value factor has revived both interest and examination of factor-based investing. Meanwhile, greater distribution of AI and ML tools has accelerated the discovery of new factors. These dynamics play out amidst continued outperformance of the "Magnificent 7" which seem to have ascended to an entirely new paradigm of valuation. Persistent, cascading anomalies that have called into question the embedded discipline of factor-based investing.

“The use of AI in asset management has been a lot more gradual and smooth than people think. But as time goes on, methods evolve, computing power increases and the results start to become more apparent,” - Bryan Kelly, AQR

Markets are complex adaptive systems, not the equilibrium-bound machines that academics see them as. New techniques, economic environments and technology will inevitably change the behavior of market participants and the tools through which practitioners derive value. As I wrote in The Sand Pile, "old theories are not really abandoned when a new theory arises but serve as referential checkpoints on our way to a more useful theoretical framework."

The Sand Pile

The natural reaction, then, is to modify the current theory as best as possible in order to accommodate reality. However, defenders of the faith can only put so many proverbial fingers in the dam. Eventually, the water gushes forth and the challenging theory gains widespread acceptance.

Pricing Power and Industry-Driven Factors

I recently attended the Bloomberg Portfolio and Index Research conference where Steve Hou presented his research on pricing power. Hou used the standard deviation of gross profit margin as a proxy for pricing power. Hou,

Intuitively, if a company has pricing power, then when costs increase it should be able to 'pass them on' to the consumers by raising prices and thereby maintaining the same profit margin.

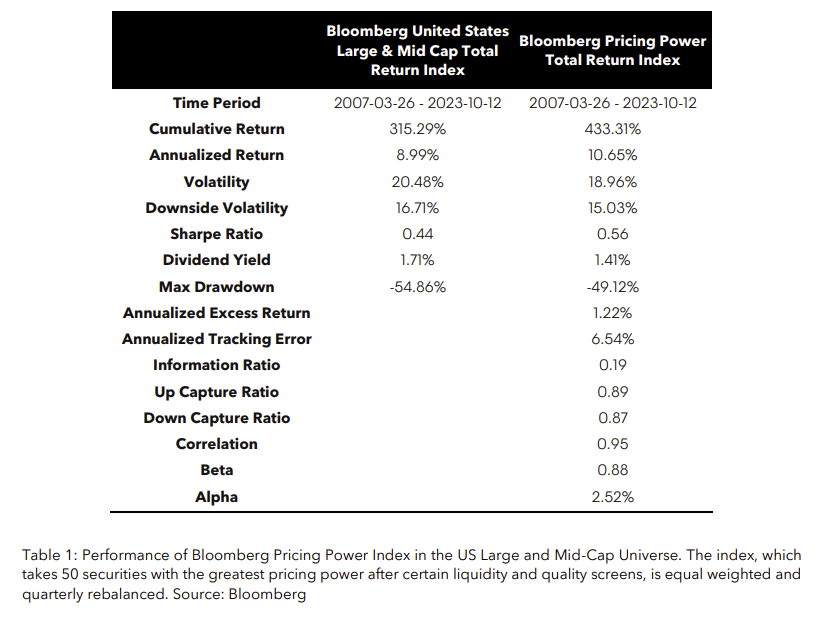

In practice, Hou's factor is the inverse of the standard deviation of 12-month gross margins over the trailing 5 years. The index is the 50 stocks with the lowest standard deviation of gross margin, rebalanced quarterly. The methodology produces good results. The index performance has lower beta, higher growth and looks more like a "quality screen" in many ways.

Hou's research suggests pricing power, as measured by stable gross margins, is a novel source of risk premia. But this premium is not idiosyncratic, it reflects the structure and dynamics of certain industries. When the factors are decomposed across regions it becomes clear that industry selection is a huge driver of alpha.

Looking at POWA, the ETF tracking Bloomberg's index, the portfolio is significantly overweight Industrials and Healthcare. The pricing power in these industries is similarly intuitive. They are protected by costly, hard-to-build assets, regulatory moats or they control supply or distribution channels. These companies were not however, traditional value stocks. They exhibited lower beta, higher profitability, but also higher growth. While all stocks are statistically integrated into the broader market, certain industries have unique drivers of return.

Traditional factor investing fails to take into account changes in the nature of public equities and evolving corporate forms. It specifically has challenges when attempting to apply the established techniques to asset-heavy passthrough entities like REITs, BDCs and Mortgage REITs.

The Asset Heavy Passthrough Problem

Equity factors themselves are not forces of nature, they are the result of economic dynamics reflected back into prices. Fama-French' (FF)s four non-market risk factors, run into some intuitive issues when applied to REITs and in multiple academic studies they tend to account for only half of REIT returns (versus 95%+ for the broad market).

Small Minus Big (Market Capitalization)

Is there excess return in smaller REITs vs larger ones? Perhaps, but it would not be for the fundamental reason that it works for other equities. For non-REITs the small cap premium comes from having more and higher ROI reinvestment opportunities. For REITs the reinvestment options are relatively uniform and capital intensive. Large firms may very well have an advantage under those circumstances.

High Minus Low (Book to Market Value)

The largest asset on REIT balance sheets is the underlying real estate, while it depreciates on the balance sheet in most cases it appreciates in real life unlike factory equipment or retail fixtures. There are ways to measure value in REITs but blunt tools like book value are not it.

Robust Minus Weak (Operating Profitability)

The high profit margins of triple net REITs versus higher touch sectors like lodging or office obviously ignores a lot of nuances. Like value itself, there are ways to measure REIT operating performance, but a traditionally run FF model will not appropriately adjust for these dynamics.

Conservative Minus Aggressive (Change in Total Assets)

Again, the investment options for REITs are relatively uniform and cyclical -- asset growth is far more contextual when the asset base is so uniform.

This doesn't mean the REIT universe offers some massively inefficiently priced risk premia, rather that that like Hou's study suggests, there are potentially factors unique to REITs that could offer sources of alpha. REITs are a compelling target for greater exploration because in general the equity tends to be more volatile than the underlying asset performance and the sector discloses more standardized (though non-GAAP) granular performance data.

It is telling that the Vatican of factor investing, Dimensional Fund Advisors, excludes REITs from their Core Equity portfolios. They argue that it makes their equity exposures more tax efficient to treat REITs as a separate asset class. Does DFA apply their disciplined factor approach when building those separate REIT baskets? No, they accept market returns from a capitalization weighted portfolio.