Public markets, not unlike public libraries, offer a clear social benefit yet if they were not already established it is hard to imagine their creation in the present. That a median wage earner with relatively little administrative friction can purchase equity stakes in some of the “best companies in the world” is beautifully egalitarian. In an age of secularly low interest rates, the ability to participate in economic growth via public equities has created retirement security for millions of Americans. Public agencies regulate trade, mediate the flow of information, and distribute reasonably robust disclosure. None of this seems like it could feasibly develop today, yet the wonder of public markets faces accelerating senescence.

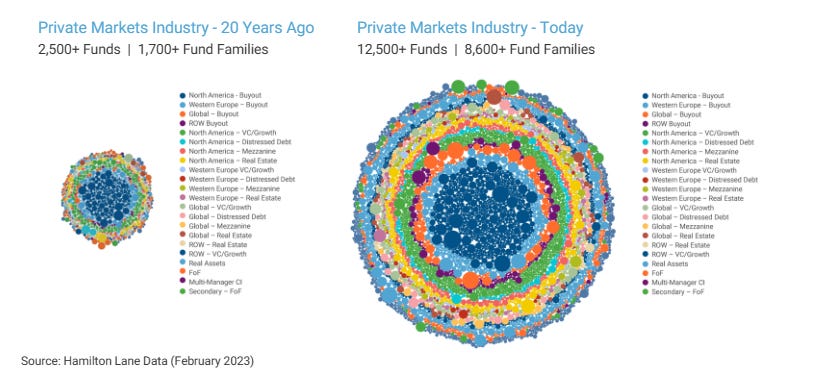

Capital formation has been dominated by private capital post-20001. The growth in private capital has infiltrated every corner of the economy. Whereas the early LBO market focused on industrial or “old economy” businesses, private equity and venture capital offer an alluring path of financing for everything from early-stage technology to real assets and infrastructure.

Private capital offers the benefits of patient capital, less onerous governance, and crucially, less disclosure2. In an economy where the precision and fidelity of data can separate industry winners and losers, the ability for certain knowledge to remain “proprietary” offers a meaningful competitive advantage. Around the same conference table, a private equity real estate manager might share with a European PE boss that industrial companies in the region are more aggressively expanding their footprint.

Moreover, certain parts of the value chain can theoretically be captive to the same equity interests, making previously thorny conflicts less limiting. In 2019, the world's largest private owner of commercial real estate, Blackstone, recapitalized commercial property restoration company Servpro. Should, for example, a hurricane inflict damage on a Blackstone-owned property in Miami, resources can be martialed from portfolio companies like Servpro to get those assets back online faster. The growth in private debt markets means private equity firms can and do often occupy multiple levels of the same capital stack. Ignoring briefly the potential fiduciary issues, captive capital markets provide a clear advantage to the providers of that capital.

The effects this increasingly concentrated ownership has on the economy is the subject of intense debate. The argument that private equity adds value by imposing greater corporate discipline is belied by the fact that in recent history growth in asset values has come primarily from multiple expansions relative to margin improvements.

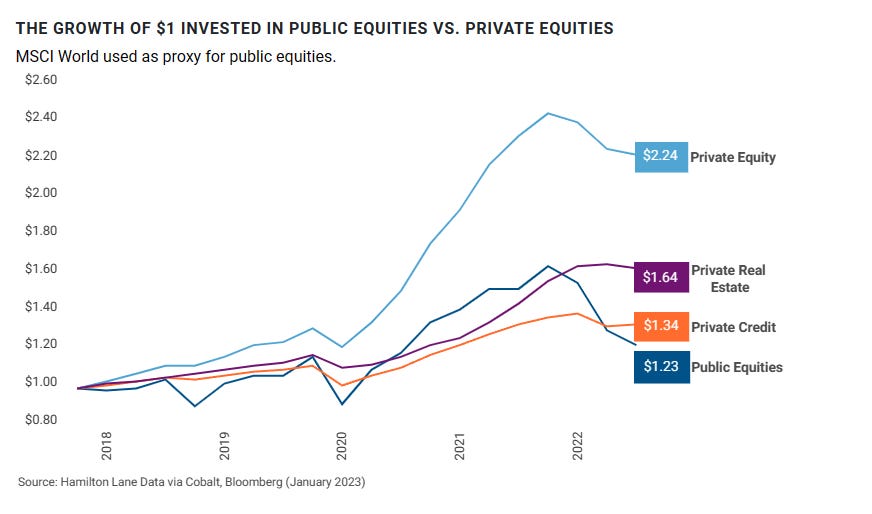

What is undeniable is that it has deprived public markets of these assets, and thus savers from the subsequent returns. Whether through luck, leverage, illiquidity, or “volatility laundering” private equity has outperformed public markets by approximately 400 basis points per year.

That the bulk of private capital comes from public pensions has been something of a raison d'etre since the asset class began growing in the 1990s, the reality though is that only 13% of the working population has or is expected to receive some form of defined benefit retirement. Endowments are another major private equity investor but those funds benefit an even smaller subset of the population.

Paradoxically, following the GFC, many of these private equity managers converted from partnerships to corporations and found their way to public markets. Once public, growth became the motivating factor for maintaining enterprise values. Instead of fighting over the fixed pie of pension and endowment assets, they turned their focus to high-net-worth and private wealth channels. These clients were ostensibly retail investors but were usually guided by financial advisors or other intermediaries. Regardless of their fiduciary status, private equity saw that these advisors could be a de facto sales force for their funds.

A lot like the difference between First Class and Coach, individual investors may be on the plane, but they aren’t in the front. Because these private equity firms do not want to build out large, internal investor relations departments they have sub-contracted the work of selling, processing, and servicing smaller investors to outside firms that spin up feeder funds and handle the deluge of paperwork required to make investments in private funds. This leads to higher transaction costs and worse experiences. While a pension fund director may be getting wined and dined by GPs, the individual investor will be paying an extra layer of fees, have little if any direct contact with the underlying managers, and wait longer for performance reports and tax paperwork. High-net-worth investors will have to assess whether the allure of higher returns and infrequently marked prices makes sense in their portfolios, especially in structures that are simultaneously cumbersome yet watered down.

For everyone else, the growth in private equity has corresponded with the degradation of public markets. In an earlier era, the IPO was the holy grail for companies with business models that had a tangible path to sustainable growth and profitability. Today, the public market is mostly an avenue for greater speculation, purchasing scrip on businesses that may generate cash for shareholders many years in the future. Low rates have meant all manner of specious businesses have been able to raise extremely low-cost, permanent capital from individual investors seeking any real return. A favorite James Grant quote,

Needing income, investors will take imprudent risks to get it. And if 2% invites trouble, zero percent almost demands it.

Even the prudent path of passive investing finds itself exposed to novel risks and challenges. The largest companies in the S&P 500 now have market capitalizations in the trillions, are generally concentrated in technology, and account for a greater and greater share of returns. For those returns to continue, these companies must find the same magic of generating high returns on invested capital when incremental productivity improvements from technology appear to be waning.

Where does this leave the average saver? With undoubtedly diminished expectations. As rates have risen, the equity risk premium has narrowed substantially, yet bonds still do not offer yields with assuredly positive real returns. In fact, monetary discourse has shifted to maintaining a higher inflation target, or even directly controlling currency to have negative nominal rates through the use of Central Bank Digital Currencies.

Such developments seem like an active effort to disincentivize savings broadly. Savings rates show that the unprecedented liquidity provided in the wake of COVID simply passed through consumers’ hands on their way to their ultimate destination on corporate balance sheets. Without a healthy public market for equity ownership, money creation is laundered through the hands of the public to a shrinking cohort of modern oligarchs.

Public markets are one of our greatest tools to combat inequality. Modern social justice parlance focuses intently on “equity” sometimes losing sight of the fact that it quite explicitly means ownership. Many policies, such as qualified retirement accounts and 401(k)s, encourage public equity participation from investors, but public markets need to regain their luster as a superior form of financing. Large employers, beyond the technology industry, should view share-based compensation as a tangible and meaningful way to attract, retain and reward talent throughout their organizations.

Problems of inequality, posturing around ESG standards, or debates about corporate taxation can be at least partially assuaged by greater public equity ownership. As certain forms of wealth creation like home ownership, small business, or even ascent through a corporate hierarchy, seem further out of reach, public equity markets remain a solution hiding-in-plain sight. More companies with real earnings and cash generation finding their way to public markets where their growth and governance can be more broadly distributed is a market-based solution already within our grasp.