Summary

Last week, I predicted that Timber REITs would be the best-performing sub-sector in 2025. This week, I am laying out my case for timber in light of its somewhat abysmal record on public markets.

Today’s post should serve as a primer on the sector and offer a few ways to think about valuation, including:

How the geographic allocation of land dictates business strategy, capital allocation, and beta to the housing market.

Which macro environments benefit timber, and to what degree does 2025 look like 2016.

Why shareholder return of capital is key to understanding valuation.

Immediately following graduate school, I went to work for a small timber fund. Timber found itself well-positioned during the height of the ESG craze. Timberland has environmental “win-win” dynamics wherein well-managed forests are both more profitable and more environmentally beneficial. Growing trees pull more carbon from the air than capital-intensive carbon removal technologies. Trees are the original carbon removal technology, absorbing the most carbon during their early, fast-growing years. When that growth and carbon capture tapers off, it is conveniently the most profitable time to harvest them into wood products.

Timber has some additional financial optionality afforded by biology. Loblolly, or Longleaf pine, the predominant species in the Southeast, has an average biological growth rate of 8% per year. That’s not a lousy inflation hedge, and should timber markets be unfavorable in a given year, you can “store it on the stump” until conditions improve.

I remember visiting our first acquisition, 1,400 acres in rural Virginia, a size downright provincial in institutional terms. After driving across a rickety bridge, bookended by deep mud, I reached a high-ground clearing roughly in the center of the property. For those used to urban or even suburban environments, the experience of seeing nothing but expansive wilderness extending to the horizon is hard to describe. With no roads, no power lines, and no structures of any kind, the world becomes a sort of biodome ensconcing you on all sides.

I’ll never forget watching a gust move across the vast landscape. It was as if the hand of God himself was brushing the treetops. The notion of “natural resources” is made viscerally tangible. I was looking at future 2x4s, paper pulp, pine straw, and diaper fillings. Such land masses provide other revenue opportunities —hunting leases, mineral rights, easements, and tradeable credits derived from everything from carbon to stream beds to habitats for native species.

To now consider that Weyerhaeuser WY 0.00%↑ owns 11 million acres of such land is hardly comprehendible. It’s more than the entire state of Maryland but a little smaller than West Virginia. When Fredrick Weyerhaeuser died in 1914, he already owned nearly as much timberland (2 million acres) as the two other U.S. Timber REITs, Rayonier RYN 0.00%↑ and PotlatchDeltic PCH 0.00%↑ , own today. Weyerhaeuser’s $30 million fortune made him potentially the wealthiest man of the era. That fortune in today’s dollars would be just $1 billion. A scale that, when compared to today’s scions of industry, inspires a different kind of awe.

Past Performance

Today, the timber industry sits at the beginning of the value chain for housing and many forms of consumer spending. As a result, it finds itself at the end of the bullwhip of changing demand patterns, global trade tensions, and wavering public interest in environmental stewardship.

Perhaps that is why timber investments, and specifically Timber REITs, have not, broadly speaking, worked. The five-year total return of the iShares Global Timber & Forestry ETF WOOD 0.00%↑ is just 5%. Over 20 years, the three US Timber REITs have basically broken even after dividends.

Note: The above chart shows price return only, although the average yield for Timber REITs has been between 2 and 3% over the time period. Additionally, Weyerhaeuser waited until 2010 to take the REIT election.

Considering these uninspiring results, it is fair to question why Timber REITs should be considered at all. As my friend Wyatt Sparks of Sea Meadow Capital put it, “We’re talking about an asset class with a duration that averages 1 to 1.5 investment careers.”

Understanding these companies and how they create and distribute value to shareholders reveals periods where timber can provide attractive returns and exceptional returns relative to broad-listed real estate.

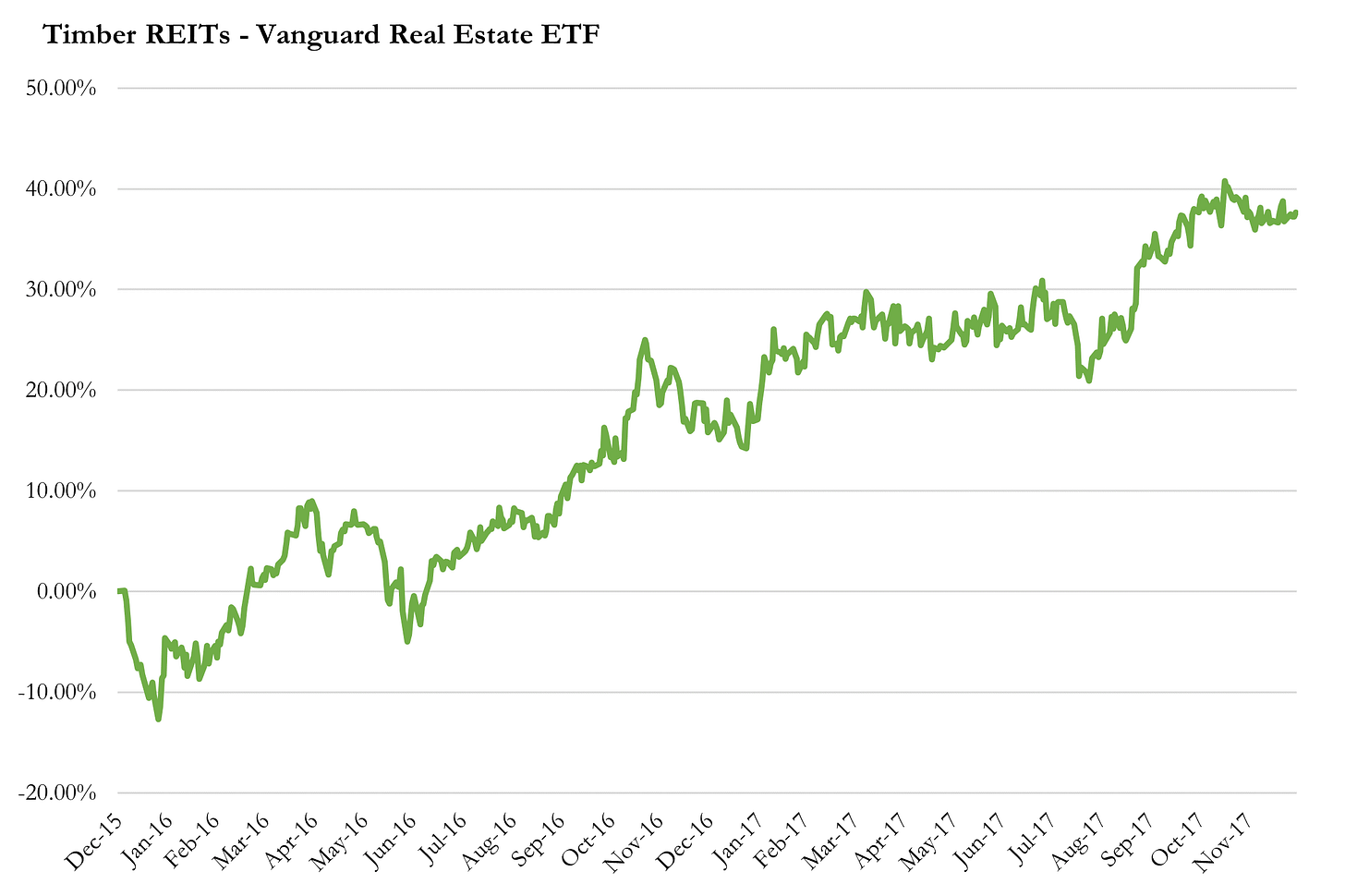

Between 2016 and 2018, Timber REITs trounced other real estate equities. This was partly driven by the macro backdrop, but it is helpful to understand the players and how they differ before we get into that.