I believe the future of alternative investments is meaningfully in flux. These thoughts are based on my own participation in the market, as well as conversations with emerging managers and associates at the largest alternative managers. I should also note that much of my time is spent in the real estate sector and many of these views are shaped by trends in that particular asset class. Nonetheless, private equity, credit, and to some degree hedge funds, are navigating changing end markets for their products. Those closer to the ground may disagree with this assessment and I’d be eager to hear an alternative narrative of how the next decade may play out. My view focuses largely on how the market structure will change with regard to investment managers, allocators, and ultimately the owners of capital.

A new BCG report ominously titled “The Tide Has Turned” points out that 90% of the asset management industry’s revenue growth has come from market performance versus inflows. Alternative investments offer an irresistibly hot dot of growth that promises large greenfield retail markets and less fee compression.

BCG recommends traditional asset managers internally build or buy alternative investment platforms. I believe they are looking for growth in a market that has already outgrown itself in many ways. The largest managers have provided a release valve for unprecedented liquidity but now find themselves with a similar deployment challenge as the capital they manage. The top five public pensions have over $1.5 Trillion in total assets, while the Top 5 U.S. alternative managers have $2.6 Trillion of assets under management. That is only to say that to the degree that investment returns come from exploiting inefficiencies, massive capital deployment begins to degrade forward returns.

To this point, the largest alternative managers have been able to capture a consistent flow of these assets precisely through their ability to deploy capital at scale. That enviable product is possible only through the magic of manpower. At Blackstone, the real estate investment headcount alone is over 1,000 professionals, a number that understates the true scale of the operation as model maintenance and other rote underwriting tasks are outsourced to cheaper labor in developing markets.

The hand-in-hand growth of pension and endowment assets and large alternative asset managers now faces a triad of headwinds. High and rising rates are changing the role of alternative strategies at defined benefit plans, mid-career investment talent is looking at crowded, relatively younger, upper echelons of their organizations, and asset growth via high-net-worth and private wealth channels requires larger and more developed investor relations functions.

Greater Intermediation of Capital

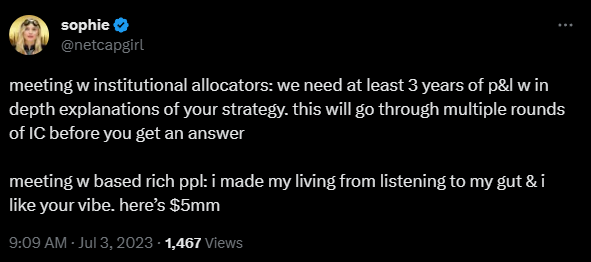

Despite weakness in traditional markets, the “denominator effect” has been muted, if not non-existent, at large pools of capital. The structural dominance of alternatives and the glacial pace of change at public bureaucracies is working in favor of the largest managers for the moment. However, performance faces its own rate-driven headwind and will eventually cause a reevaluation of investment policies, and ultimately, greater intermediation of capital allocation. Institutional capital will go in search of the inefficiencies large alternative managers can no longer provide. This is an important development because simultaneously the top mid-career talent at large alternative managers will leave to start their own firms in an effort to make more interesting investments and to access more remunerative general partner economics. The layers between capital and assets are going to increase and specialize.

This will open up capital to emerging managers across asset classes, but today’s managers must start with a more diverse capital base that includes institutional capital, HNW/Private Wealth, and OCIO relationships. Absent a change to the market structure, alternative managers face one of the classic business challenges: Selling into multiple markets at once without sacrificing product quality or brand.

Today, you have emerging alternative managers building what are essentially DTC brands on social media, established firms utilizing crowdfunding sites to diversify their capital bases, and independent advisors getting aggressively marketed alternative strategies by their traditional investment providers. The challenge of a more fragmented, or intermediated, market of capital providers is that the investment business begins to demand increasingly sophisticated “distribution.”

Distribution is a bit of an anachronistic term in asset management that harkens back to a Golden Age of Wirehouses. Distribution is, in fairness, still regulatorily captured by broker-dealers. For the largest asset managers, this regulatory relic is a trivial detail and an even more de minimus cost of rolling out retail-ready products that can profitably accept smaller checks1.

For smaller managers though it can be both a significant cost and meaningful distraction, especially if their AUM does not support a large organization. Firms like iCapital and CAIS have tried to fill this void by taking on some of the administrative and marketing burdens of accessing more retail dollars. But these platforms still lean heavily on the brand strength of “Blue Chip” alternative asset managers, while respected, but not-yet-household-name, firms struggle to attract assets.

These disjointed sales channels and access points are clearly not an end-state for the market. The current fragmentation is creating temporary profit pools for those offering “access” to something that is already broadly accessible, just confusing and poorly mediated. Marketing to retail investors is costly and risky without more certainly around customer lifetime value. Retail capital is notoriously fickle and running illiquid strategies that rely on it has a long history of failure.

The Distribution Layer

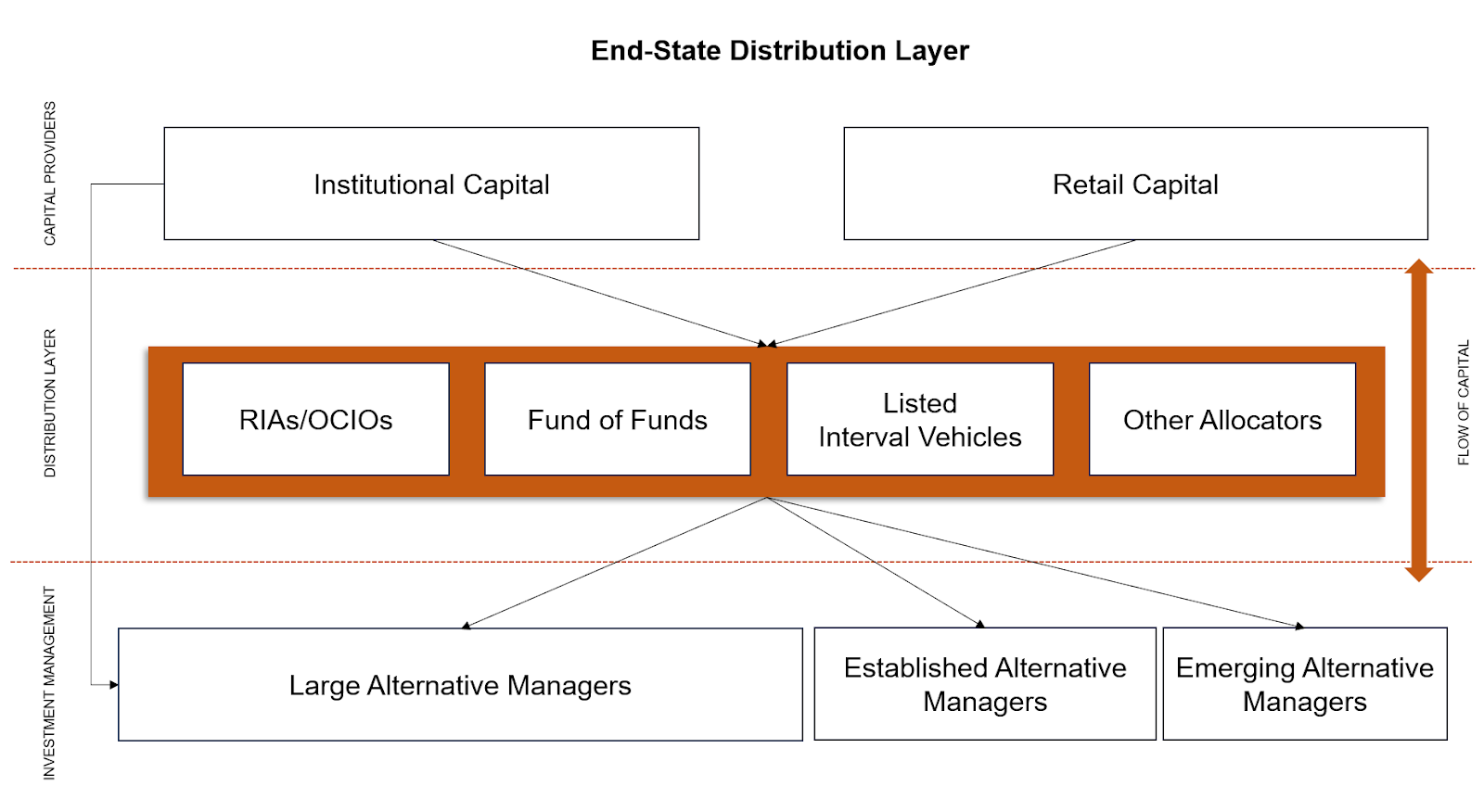

I believe there will be a growing Distribution Layer of capital allocators that sit between investment managers (both emerging and established) and investors (both institutional and retail). Registered Investment Advisers “RIAs”, specialized fund-of-funds (FoFs) of various structures, and Outsourced Chief Investment Officers (OCIOs) will all inhabit this layer. These all exist today, but I believe they will be the actual growth market within the private capital landscape. They will grow in number, assets, and overall importance to the market over the next decade.

The language of “access” will continue to lose currency, while mediation, diligence, and process will attract capital. While the largest managers will maintain their relationships with institutions directly, they will access private wealth and retail channels through a Distribution Layer. Established and Emerging managers will sell products into a Distribution Layer that faces these firms in a more traditional B2B relationship format.

Platforms like iCapital or CAIS have a tenuous first-mover advantage. They provide commodity infrastructure and back-office support for investment managers, but the role of investor relations, communications strategy, and marketing still falls primarily on the managers. This is the key benefit to managers of a growing Distribution Layer: It is a largely homogenous group that can all be marketed the same product, with the same language, and the same sales force.

Institutional capital will be attracted to the Distribution Layer as a way to scale their own allocation efforts towards portfolio optimization, greater diversity, and more inefficient sectors of the market. An OCIO or sector-specific FoFs will offer a way for institutions to continue to deploy large checks but do so in a more diffuse way.

Perhaps most importantly, the Distribution Layer will also act as a clearinghouse for capital with different durations. Liquidity concerns will be handled at the distribution level, not the investment management level where illiquidity is a key driver of returns. Currently, managers are having to innovate new, often clunky, sub-optimal versions of their strategies to accept capital of varying liquidity expectations.

Capital will flow into the Distribution Layer where firms will build allocations from different buckets of capital, allowing investment managers to focus on investing and institutional allocators to focus on tuning and optimizing their portfolios.

Early Iterations

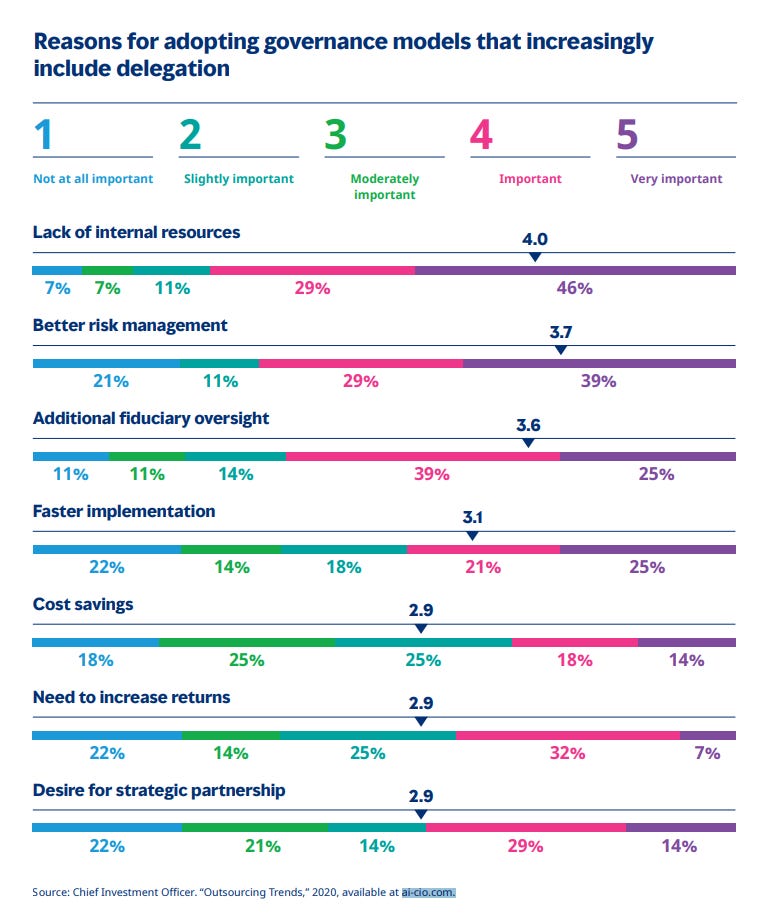

Institutions are currently supported by a consultant ecosystem that provides a governance prophylactic for institutional decision-makers, but they are not principals like the firms that will occupy the Distribution Layer. Some RIAs and Multi-Family Offices are performing distribution-like roles, either via captive Fund-of-Funds or by convincing alternative managers to aggregate smaller checks but face the investment manager as a single LP.

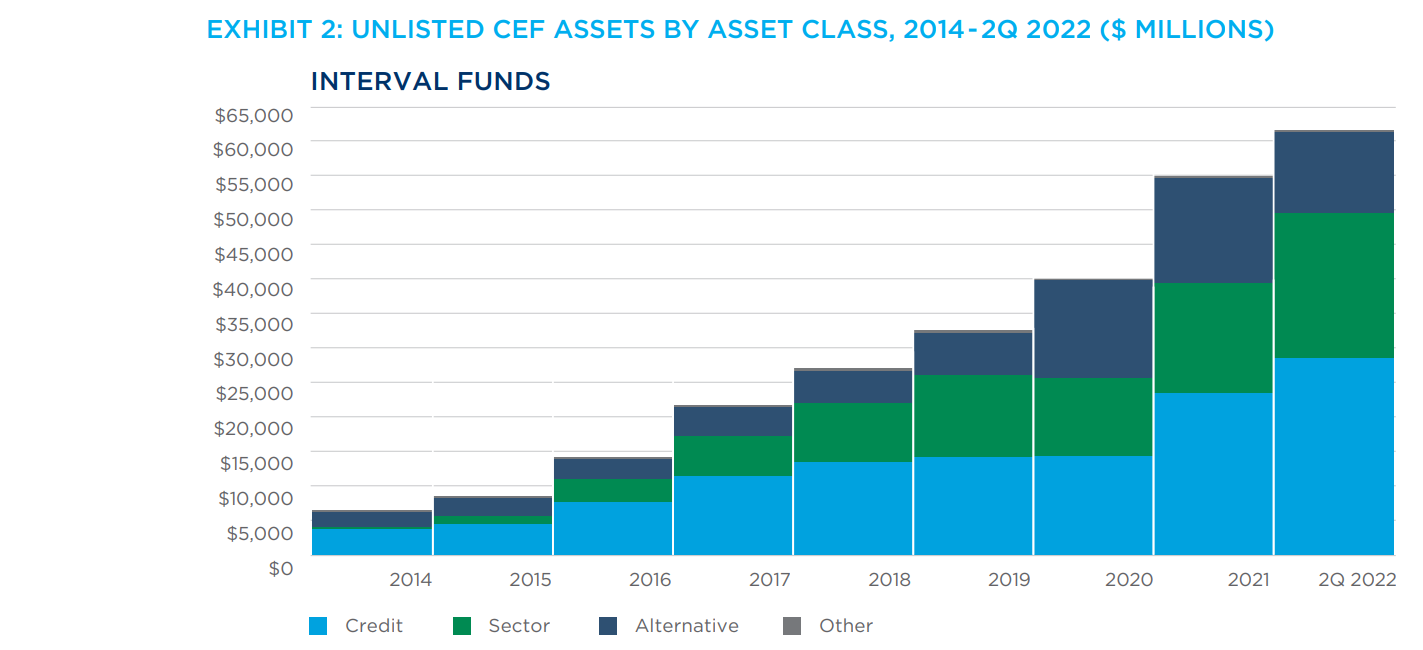

Interval funds are making inroads into the Distribution Layer as accessible allocators to private assets. This structure is not without drawbacks2, but it does fit the profile of being able to continuously accept and allocate capital from diverse capital sources with varying liquidity requirements.

Sector-specific allocators and Fund-of-Funds will also be able to attract assets as key players in the Distribution Layer. Private equity, real estate, and credit are asset classes with high transaction costs and considerable friction. Specialization within these categories is a forgone conclusion, but with specialization comes a more limited capacity to deploy capital at scale. Fund-of-Funds and similar structures with asset class-specific mandates help institutions optimize exposure without expanding internal resources.

Interestingly, the largest alternative managers have had limited success in participating in the Distribution Layer themselves. Assets under management at Blackstone Hedge Fund Solutions, which allocates to external hedge fund strategies have grown at a much slower clip than their core Private Equity and Real Estate offerings. Carlyle Group purchased AlpInvest in 2011 ostensibly as a bolt-on secondaries platform but has evolved to provide “Investment Solutions” via primary, secondary, and co-invest private equity investments to institutional clients. At the time of the acquisition the firm had $43b of assets under management, 12 years later AUM is only $68b, growing just 4% annually since the acquisition. Despite anemic growth thus far these may prove to be valuable business units, but I still believe there is a broad mandate across the capital spectrum to achieve greater manager diversity within the alternatives sleeve.

Impacts

A perfectly reasonable argument against this view is that a focus on minimizing fees will prevent a new layer of intermediation from forming. I would argue that running multiple sales channels, disjointed access points, and spinning up internal IR teams is adding considerable cost to the overall system. The Distribution Layer requires no regulatory disruption or moonshot technology, just growth capital to capture the opportunity. The business model of charging a nominal percentage of assets is well beyond proof of concept.

I think the most salient change to the market will be how investment firms position themselves in the market and the investment strategies they ultimately choose to pursue. Today, firms must shape their offering to an impossibly broad set of capital providers. The end-state Distribution Layer will afford managers the freedom to specialize, pursue truly inefficient markets and take advantage of time-limited or capital-constrained opportunities.

In the previous two decades building an investment business meant building a capital-raising machine more than developing a process generating investment returns. Gathering assets will always be a crucial function within firms, but it shouldn’t supersede the task of making great investments. My most pollyannish view is that the Distribution Layer will allow investment firms to focus on developing the best possible investment programs, and those processes will serve as the chief content that allocators will look for when making their decisions. That’s starkly different from the current state where the path to growth is quickly spinning up a product to catch flows from an undefined, shifting glob of global capital.

If not, I still believe the canard of access will give way to greater mediation and thoughtfulness around alternative allocations. Global private equity is about twelve times the size of the public markets. Progressively later state venture capital and the growth of buyout firms have deprived public markets of many of the fastest-growing and best-value companies. At some point these assets are no longer “alternative” but core to earning equity risk premium.

The growth of alternatives is less about attracting investors to something new and more about adjusting their allocations to something that is. That evolution will demand new skills, new firms, and new practices throughout the investment value chain.

Further…

Many of the crypto projects of 2020 and 2021 were, in essence, looking for a regulatory path around broker-dealers. That effort to circumvent what has been a very profitable capital markets toll booth is now attracting the ire of regulators.

Setting monthly NAVs creates more alignment issues than the disclosure challenges it seeks to solve. Furthermore, as evident by recent events, liquidity gates can create redemption vortexes that undermine the core benefit of the structure.