Basic Capital: It Takes Money to Make Money

The undeniable logic of Basic Capital

Capitalism works. Especially for those who own capital. It is rather astonishing that some might propose abolishing capitalism instead of simply expanding the ownership base of capital.

All quotes in this piece are from Basic Capital founder Abdul Al-Asaad’s Harvard Innovation Lab whitepaper. There is a link to download the paper at the bottom of the post.

Credit markets have fundamentally transformed the investment landscape. An extended period of historically low interest rates has reshaped investor behavior, making leveraged positions increasingly attractive while rendering traditional unleveraged equity ownership appear conservative to the point of obsolescence. While the credit cycle is not new, our current paradigm seems unusual in its appeal to both borrowers and lenders. The Biblical admonition to “Neither a borrower nor a lender be” has given way to “both a borrower and lender be.”

The recent virality of Basic Capital is reflective of the mood. The product, the firm, and its founder, Abdul Al-Asaad (AA), were all thoroughly covered elsewhere a few weeks ago. Less covered was Al-Asaad’s Harvard white paper that laid out the intellectual case for the “pre-distribution” of capital. I’ll get to the term later; what’s compelling to me about both the product and the discourse it inspired is the continued desire for markets to deliver a specific outcome to participants: Retirement.

A demographic wave, on the cusp of transitioning from net savers to net spenders as they exit their prime earning years, meets the tumult of AI potentially cutting short a generation of workers entering theirs. When combined with waning population growth in advanced economies, the fabric of how labor and capital co-exist is beginning to fray.

AA provocatively includes “closing the wealth gap” in his title, but the primary focus of the paper is retirement, how it is traditionally funded, and why, in our financialized economy, new approaches are required.

Flawed Assumptions

There are three primary structures of retirement savings: the rapidly vanishing pension, private savings plans (such as 401(k)s and IRAs), and “pay-as-you-go” systems like Social Security. It’s worth focusing on social security conceptually because it captures the primary allocation decision most Americans face — their relative exposure to human capital and financial capital. Implicitly in the U.S. and explicitly in France, social security is a “social contract between generations,” where current earners finance the retirement of an older generation.

A central pillar of the design of the Pay-As-You-Go system is the inherent diversification it offers across the two sources of input (and hence income) in the so-called “Cobb-Douglas production function,” named after economists Charles Cobb and Paul Douglas who first proposed it in 1928. In its most standard form, the Cobb-Douglass production function states that there are two main factors of production: labor and capital.

Hence, at any point in time, any active member of the labor force has two potential sources of income: labor income from work and capital income from return on savings. Assuming every active worker saves, active workers are fully diversified across these two factors of production because they have labor income from work and capital income from savings.

Like all economists, Cobb and Douglas had a fixation on equilibrium. They believed that labor and capital incomes were perfect substitutes with an elasticity of 1. In plain language, if you could replace your income from the earnings on your capital, you would stop working. As more people did so, the returns on capital would fall, pushing people back into the workforce. Over the long run, the balance of labor and capital’s respective share of national income would be stable.

As someone reaches retirement age, their returns on human capital decline. If Cobb-Douglas were true, a combination of private savings and pay-as-you-go retirement schemes would work. Retirees’ allocation to factors of production would remain balanced between capital return on their savings and exposure to human capital through social security. AA argues that it does not, and the lived experience of most retirees shows that they are heavily reliant on capital returns to fund their lifestyles.

Capital Wins - r > g

Economists think: if capital income is high, saving is more attractive, which then

grows the stock of capital, and eventually capital income ought to decrease.

This is a perfectly logical, yet empirically untrue, assumption.

Economists have long concerned themselves with the relative advantages of capital. AA notes that as early as 1817, David Ricardo warned that the increased economic output would disproportionately accrue to landowners, possibly to the point of causing social unrest. Later, following the Industrial Revolution, Karl Marx expanded on this sentiment. Noting that now freed from the constraint of land scarcity, capital is infinitely reproducible.

Those who already have capital have a higher capacity to accumulate more of it by investing. Both believed these systems were unsustainable, and both were ultimately proved wrong. Writing in the late 19th century, they had a forgivable blind spot for the impacts that technology and innovation would have on productivity and, in turn, returns on capital.

It is the same oversight that upends Cobb-Douglas. The supply of capital can increase without the returns to capital decreasing. Innovation increases productivity; so long as the demand for capital outpaces the growth of its supply, returns can outpace the accompanying growth for a long, long time. They have:

The ever-increasing rate of return on capital seems to be desperately trying to

inform us that capital always finds a home: whether it is in the development of new electric vehicles, like Tesla, or in new geographic frontiers, like India. I’m not entirely sure why economists find it inconceivable that the rate of return on industrial capital will continue to increase as the stock of capital also increases.

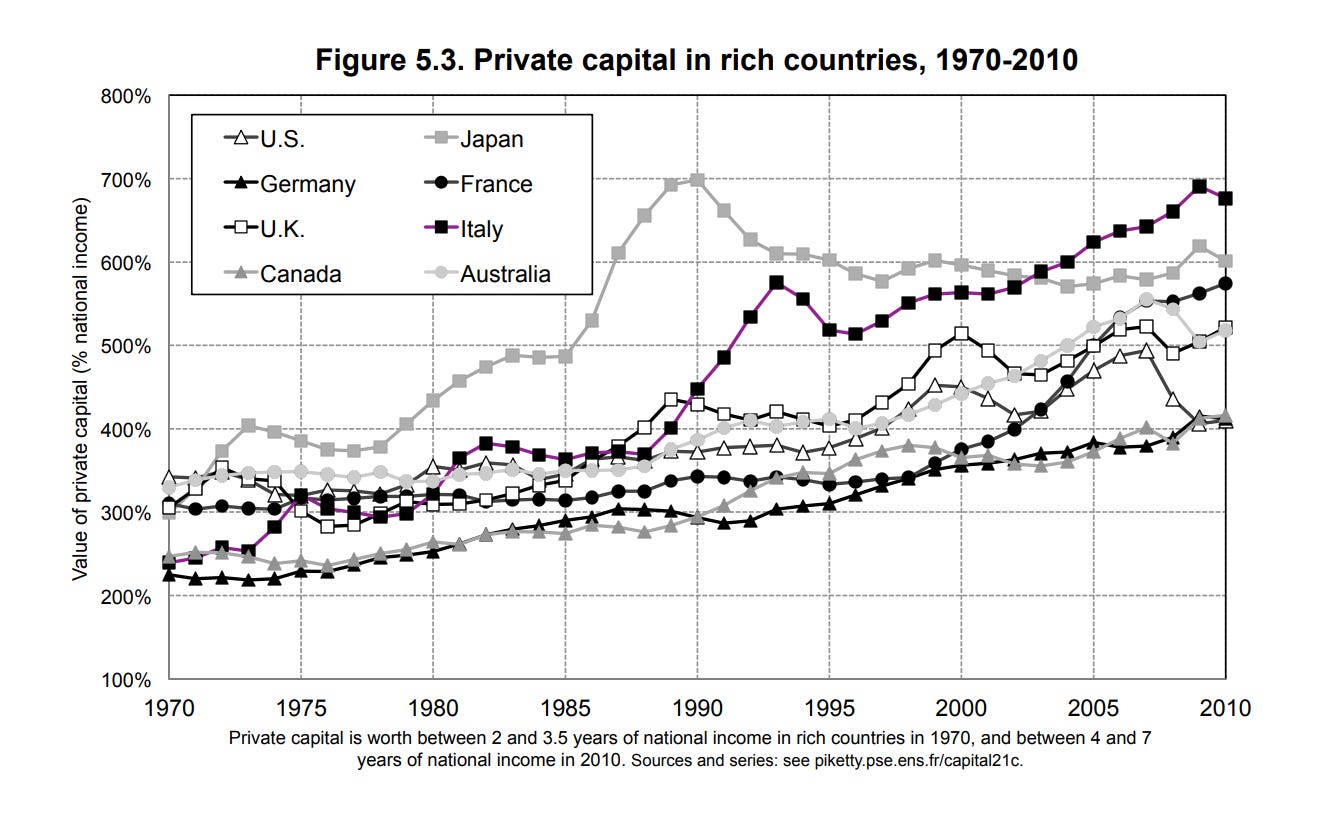

AA leans heavily on the work of Thomas Piketty1 and the idea that “r” the return on capital can outpace “g” for extremely long periods. This drives ever-greater inequality as financial capital compounds at a rate far faster than the economy and, by extension, the rate at which wages grow.

Initial Endowment Effect

It is practically impossible to form and accumulate wealth via savings in late-stage capitalist nations.

Labor’s share of national income shrinks as productivity gains are disproportionately captured by the owners of capital. A blackboard solution to this problem is simply for people to save more, but in a period of stagnating wages and above-trend inflation, that “solution” is some mix of callous and impractical. Thrift may be a virtue, but not one we necessarily live out as options for consumer credit proliferate, fueling growth of consumption and further improving capital returns.

It is important to highlight that there is not anything inherently problematic about

capital outpacing economic growth or wages. If capital ownership is evenly distributed, then society as a whole can benefit from this divergence. The critical insight here is that in advanced capitalist societies where growth is slow, the initial capital endowment plays a vital role in wealth formation. Hence, it is especially important for citizens of advanced capitalist societies with low population and rapid technological growth to own capital assets.

In terms of closing the wealth gap, a noble but perhaps futile goal, or the more immediate concerns of funding retirement for a workforce in a lower-growth economy, there is little that can be done to overcome the advantage of starting with a larger capital endowment.

AA uses a capitalization model to illustrate the point. In real estate, a property that trades at a 5% cap rate can be thought of as a 20x multiple on operating income or, more simplistically, that it will take 20 years of income to recoup the purchase price. The same property purchased at a 10% cap rate will have a 10-year payback period.

For savings, the logic is similar. It will take someone saving 10% of their income 10 years to save one year's income. If they earn 8% on those savings, the timeline drops top to just under 8 years. Now consider that same person with a $100,000 income who already has $100,000 in savings. Saving 10% of their income and earning another 8% from capital, they will have replaced a year of income in under 5 years. With $500,000 of savings, they are replacing a year of income every two years. Starting from $0 and saving 10% of a $100,000 income, earnings 8%, it will take 20 years of working to accumulate $500,000 of savings.

Don’t get intimidated by the numbers; the point is simple: in periods of slow economic growth, the initial capital endowment critically impacts the implied savings rate and the capacity for wealth accumulation because it inflates the implied savings rate if the returns are reinvested.

Broad-based re-distribution of capital is politically fraught to the point of being a non-starter, nor is it entirely clear it would provide a long-term solution in a late-stage, financialized economy. Expanding or enhancing social security is also impossible without a growing workforce with growing wages.2 Pre-distributing capital is the only remaining solution.

The present phenomenon of wealthy boomers jumpstarting their own children’s wealth accumulation through home purchase assistance is a form of pre-distribution of capital. The creation of government-sponsored home lending is a more institutionalized version of capital pre-distribution. The Basic Capital product is a private version of capital pre-distribution funded by private sector debt. It differs substantially from the proposal AA ultimately lays out in his paper, but such is the nature of financial innovation. It is unlikely, in my opinion, that the current iteration of Basic’s offering is the end-state of private pre-distribution efforts.

While we seem to have no problem extending credit for consumption or for depreciating assets, or offering wrapped leverage to investors for speculation, the notion of extending revolving credit to purchase financial assets hit a nerve in financial circles. As is often said, leverage enhances outcomes, but it does not necessarily improve them. The merits, drawbacks, and risks inherent in the product were pilloried as yet another transfer from savers cast as rubes to sophisticated financial engineers. AA,

The question is not whether financial innovation and action can lead to increased risk. More financial activities inherently mean more risk. The question is, rather, who benefits from this increased risk, and more importantly, who benefits from the lack of action and financial innovation? The extremely affluent and sophisticated capitalist class have always benefited from debt-based financial innovation and have always privatized gains and socialized losses…

The question is not whether innovation belongs in the financial sector, rather, who does the innovation primarily benefit? And whether we can afford to move forward without innovation the financial sector.

The Rise of the Rentier

People’s response to the environment provides the basis of economic truth, not theoretical models. By that measure, society has internalized the ideas of AA’s paper even if they’ve never heard of Cobb, Douglas, or Ricardo.

Working for a living is increasingly seen as a loser’s path. A friend of mine is in a family of doctors. When he hangs out with his siblings and their fellow M.D. friends, they all express a desire to practice medicine only long enough to build a portfolio of rental real estate to live off of passive income. These are people who have trained in their chosen field for more than a decade in some cases, and yet they view being a small-time landlord as a more appealing path.

Giant social media followings are dedicated to escaping the labor class by purchasing small businesses. Interestingly, this path often involves taking on a high degree of personally guaranteed leverage from the Small Business Administration. There is no outcry about the recklessness of this version of capital pre-distribution. Why is taking a government-sponsored loan to buy a plumbing contractor seen as more noble than simply working a job with an equivalent degree of leveraged exposure to financial markets?

Finally, there is the question of retirement, which increasingly requires a full commitment to capital returns, given the dire outlook for Social Security’s sustainability. I wrote earlier this year about the rising popularity of annuities. In that arrangement, savers are the providers of leverage, handing over their capital endowments to private equity firms that apply ever-increasing layers of debt to generate financial returns. AA merely proposes inverting that structure.

Increasing the supply of capital may not drive down capital returns, provided innovation continues apace; however, as AA notes, more financial activities invariably increase risks. Privatizing gains while socializing losses has certainly not embedded a sense of financial prudence. If reversing the march of financialization is pollyannish, then spreading those risks more broadly may be the more moral path. At least then, both the upside and the downside would be socialized.

Piketty's r > g framework has faced substantial criticism from economists on multiple grounds. The most technical critiques focus on the "elasticity of substitution" between capital and labor—for r > g dynamics to persist, this must exceed 1, but most empirical studies find values below 1. Lawrence Summers and Matt Rognlie argue Piketty conflates gross and net returns, noting that modern capital (like software) depreciates much faster than historical equipment, potentially negating his thesis when accounting for depreciation.

Critics also challenge Piketty's broad definition of "capital" as actually measuring wealth (including land appreciation) rather than productive capital goods. Many economists argue inequality stems primarily from other factors—technological change, globalization, educational premiums, and labor market institutions—rather than capital-labor dynamics.

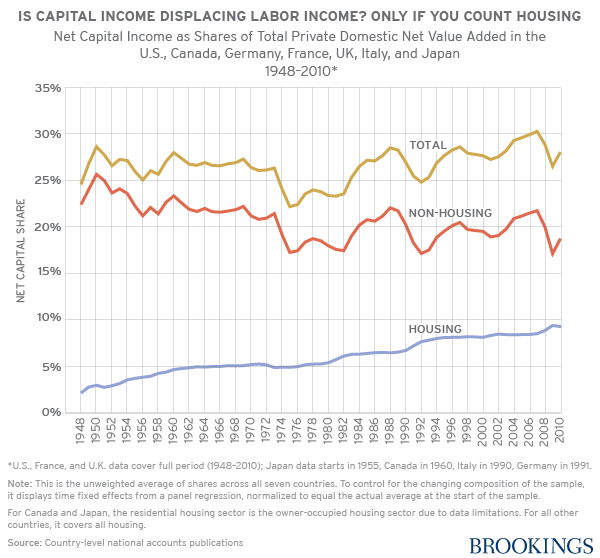

With regard to wealth distribution, the Brookings Institute notes that a large portion of Piketty’s chart is explainable by the increase in the value of housing, which is more broadly distributed. However, that broad distribution was itself the result of policies and financial products designed to offer concessionary financing to homeowners…a form of capital predistribution.

Absent simply filling the gap with more Federal borrowing. I’m not sure there is an upper limit, but if there is, offsetting the wealth disparity for subsequent generations of retirees with debt-funded entitlements would certainly test it.

"Broad-based re-distribution of capital is politically fraught to the point of being a non-starter, nor is it entirely clear it would provide a long-term solution in a late-stage, financialized economy"

It's politically fraught in the current environment but the future electorate will rapidly be comprised of the people that suffered the consequences of an over-financialized economy and who already demonstrate redistributionist beliefs. Selling them on an an even more financialized solution to their problems that carries high fees and leverage seems like it could be tough.