In the world of pensions and endowments the preponderance of asset allocation as the primary driver of returns is practically a truism. The wisdom of this approach was codified in Harry Markowitz’s Modern Portfolio Theory and further lionized by Yale’s David Swensen who added then-exotic “alternative assets.” Real assets, private equity and hedge funds with their disparate correlations to stocks and bonds unlocked the allocators’ holy grail: Higher returns, with less overall risk.

Alternative assets have benefitted unusually well from this approach as periodic rebalancing between the more volatile public asset classes and the optically stable private markets almost always meant a fresh flow of capital. Bond yields’ 30-year downward march and the post-GFC growth in equities meant allocators were constantly topping up private allocations.

The increasing flows meant more capital chasing the underlying assets which bolstered returns. Those steady returns, driven mostly by multiple expansion, are now creating a fundraising challenge. Without a bust, there can be no boom.

Shannon’s Demon

What follows here is a very abbreviated description of Claude Shannon’s concept. I highly recommend checking out RQA’s or Portfolio Charts’ more detailed write-ups.

Despite the mathematical complexity of Modern Portfolio Theory in practice, its primary feature is nicely illustrated through Shannon’s Demon a thought-experiment developed by MIT mathematician Claude Shannon. Richmond Quantitative Advisors,

The general idea behind Shannon’s Demon is that two uncorrelated assets, each with zero expected long-term returns, can actually produce a combined portfolio that consistently generates positive returns if intelligently balanced and rebalanced at regular intervals.

Imagine a fair coin, when flipped you can either make 50% or lose 33.3% making the long-run expected return of the game zero. Start with $1,000, flip once, win $500, flip again lose $500 ($1,500 x .666), back at $1,000.

100% Coin Portfolio

50/50 Coin-Cash Portfolio

If instead of betting $1,000, you bet $500, keep the other $500 in cash, also with a 0% return, and diligently “rebalance your portfolio” after each flip into 50% coin outcome, 50% cash you can transform two assets with 0% expected return into a portfolio that generates an ~8.4% return.

Volatility Drag

The experiment demonstrates the impact of volatility, and more specifically volatility drag, on portfolios. Richmond Quantitative Advisors,

To better understand volatility drag and the power of it, assume you have $100 to invest. In the first year, you make a 10% return. Then in the second year, you lose 10%. Intuitively, many people would think you’re back to breakeven, but you’re not. You’re actually down 1% from where you started – $99. Moreover, the greater the size of these return swings (i.e. the greater the volatility), the more the volatility drag increases – and it grows exponentially! For instance, if your return swings were 20% instead, then you’d be down 4% after the second year. Even though volatility only doubled (10% to 20%), the volatility drag quadrupled (-1% to -4%).

By rebalancing into an uncorrelated asset, in this case cash, you reduce the volatility drag substantially. That volatility reduction allows you to collect the geometric, or compounded return of 8.4% versus the arithmetic mean, or average return of zero.

It is a neat trick, but aside from the obvious simplifications relative to real-world investing, the coin and the outcome are known with certainty at the end of each flip. The messier world of institutional investing does not have this luxury.

Disrupting the Demon

While the return profiles and correlations get more complex, the basic management of institutional assets follows the logic of Shannon’s Demon. Allocators assess returns and then dutifully rebalance back to the target allocation. If equities are down big, like in 2022, funds are allocated to them to bring the portfolio back into balance. Allocators may make some tactical shifts to justify their existence, but substantial changes to the investment policy are herculean, politically fraught endeavors.

The issue arises for private equity when the coin just never lands. There has always been some question the degree to which private equity was actually less volatile or merely disguising the volatility through infrequent valuation. The considerable uncertainty and likely loss of value within real estate in particular not yet reflected in private marks is beginning to get uncomfortable. Globe St. reports that pension allocations to real estate funds are down 50% this year,

The tally from commitments to funds and separate accounts last year was the lowest since 2013, when pensions gave less than $28B to CRE and the fourth-lowest total since Ferguson Partners began tracking the sector in 2011,

Traditional buyout firms and venture capital aren’t faring much better where the Financial Times reports that across private equity, fundraising is the lowest it has been since 2017. The FT,

However, after a decade-long industry boom, private equity groups have been struggling to sell portfolio investments and to convince investors to lock funds up for long periods with high fees attached.

The same reflexive nature that powered private equity’s growth now threatens to be its undoing. In the seemingly interminable cycle that began a decade ago, investors have grown accustomed to “V-shaped” asset recoveries. Private equity did not rush to mark-down assets, which would jeopardize their trademark stable values if new highs powered by lower rates were always just a quarter or two away.

That impulse has disrupted Shannon’s Demon. The volatility drag isn’t being rebalanced away, it’s being carried. The rebalancing that would occur with a realistic assessment of Net Asset Values drives the reversion to the mean that Modern Portfolio Theory relies on. Capital would flow into sectors with depressed pricing and those assets would get bid up.

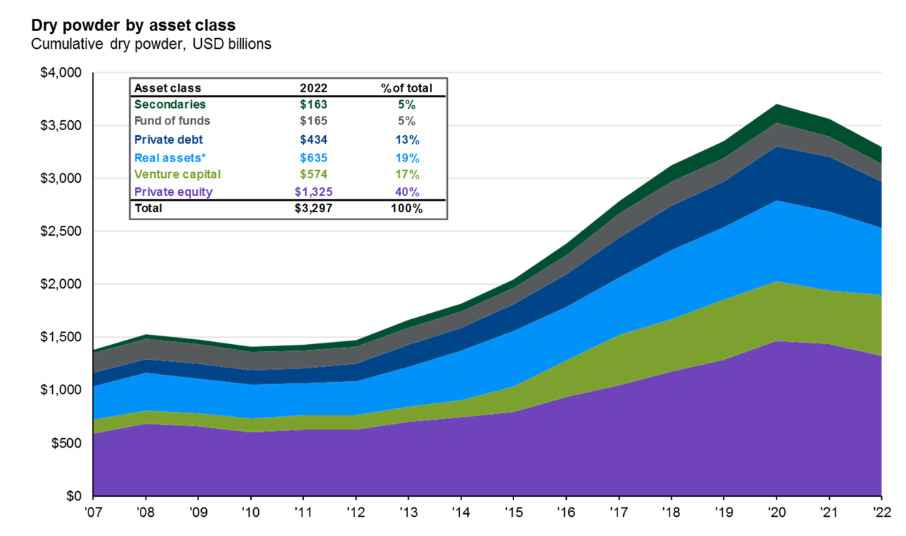

Dry Powder

Much has been made about the uninvested capital still sitting within private equity vehicles. These sums are cited either as proof that the party can go on, or simultaneously that it’s winding down. In reality they represent a sort of stalemate. It is hard to buy assets that look very much like the ones you already own for attractive values while maintaining that yours are not similarly valued.

Ultimately transactions, not models, set prices. While the stalemate can’t go on forever, certain palliative solutions have arisen. The growth of secondary funds to buy existing LP stakes as well as the rising popularity of co-invest vehicles that have lower fees and focus on deal-by-deal acquisitions are currently taking the place of fresh fund capital.

Volatility Transfer

The industry may get another form of bailout in the form of surging public equity values. Not only do all-time-highs shift the denominator in favor of greater private exposure, but IPOs may offer the liquidity currently absent from private markets.

Recall, Shannon’s Demon is an illustration of reducing volatility drag by rebalancing between assets with different correlations. When private equity obscures the underlying volatility it doesn’t disappear, it merely gets carried along.

Moving it to a more volatile asset class via public offering brings the system back into balance. The 2021 SPAC boom provided a preview of this for venture capital excesses. Now expect public markets to absorb the detritus and carried volatility of private equity and real estate. On Apollo’s ( APO 0.00%↑ ) latest quarterly call, CEO Marc Rowan said that he “sees an opening” to push private capital into the 401(k) market. Rowan,

It's limited by a risk mentality as a result of substantial litigation over a long period of time, but I think we're seeing a stabilization, particularly as the set -- suite of private products is no longer all high fee, high carry, locked away in funds.

You're watching the first baby steps as fiduciary managers in 401(k) begin to mix-in private into their, heretofore, public solutions simply to get better outcomes and better diversification.

If successful, private equity can print the returns that have powered its growth through the decade. But if the carried volatility can’t be offloaded and hits the asset class, asset allocation assumptions that created a growing pie of capital for decades may be re-evaluated. Private equity should have let the coin land.

Further…

Inside the Private Equity Options Factory

The emergence and growth of GP Stakes investing is the latest of late-cycle phenomena, a motley chimera of structures used to amplify the productive output of the private equity options factory.

L.E. Memo | The End of Thrift

In an age of secularly low interest rates, the ability to participate in economic growth via public equities has created retirement security for millions of Americans. Public agencies regulate trade, mediate the flow of information, and distribute reasonably robust disclosure. None of this seems like it could feasibly develop today, yet the wonder of public markets faces accelerating senescence.